As of 2021, there are 40 national parks in Finland. Those are state-owned territories which are kept in a natural state (as much as possible, and sometimes with traces of traditional agriculture, forestry and fishing) and are suitable for hiking and other recreational activities. 40 is already quite a bit for the country the size of Finland; Sweden, for example, despite being larger and more geographically diverse, has only 30. Yet even more national parks are coming; Salla national park in East Lapland is already on its way (the law establishing that national park has been proposed to the parliament in June 2021) and likely also Evo in a remote part of Häme will follow.

And so trying to visit all Finnish national parks is a bit of a catching-up game, but still the new ones are being established slowly enough that visiting the existing ones is totally possible, and many people have done that. For myself this became a goal perhaps some two years ago, when I realized I'm already well on the way to doing this. I did a lot of catching up in 2020, when I could travel around Finland quite a bit, and for 2021 there was only the final one remaining: the Bothnian Bay National Park (Perämeren kansallispuisto), established in 1991, with its main island of Selkä-Sarvi.

This national park often ends up being the last one for other "national park collectors" in Finland, and is generally the least visited one of all 40. Only about 5000 people visited it in 2020, over three times fewer than the next least visited one. (Visitors are counted by automated counter devices, which are not especially precise of course but numbers for different national parks should be comparable.) This is simply an annoying one to visit!

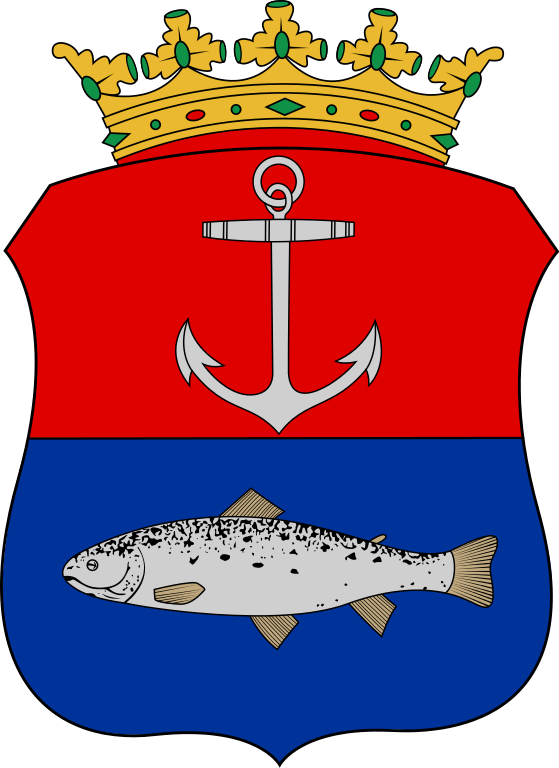

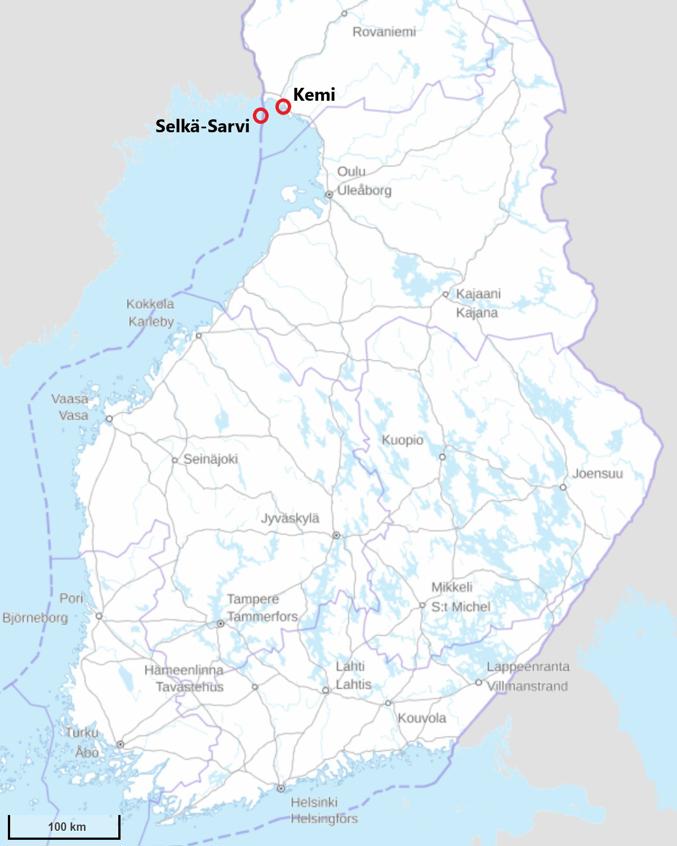

The Bothnian Bay National Park, as the name suggests, is a marine national park, centered around some of the northernmost sea islands of Finland. Its total area is 157 sq. km, but only 2.5 sq. km of that is dry land; smallish, sandy, nearly flat islands, covered with juniper, deciduous groves and still retaining some fishermen huts. The problem is simply that the Bothnian Bay area is relatively remote for almost everyone, except the residents of Oulu and the nearby smaller cities. From Helsinki for example it is an over 700 km drive or at least a 7 hours long train trip, making a day trip impossible and even a weekend trip exhausting. And the dates must be carefully chosen, because there are only a few public tours to the national park every summer. (Of course, if you can travel by your own boat, it's a completely different matter.) The tours depart from the city of Kemi, population about 20,000, an industrial but surprisingly nice town, the second last one before the Swedish border. (They also departed in the past and might depart in the future also from Tornio, the actual bordertown. A private "water taxi" certainly can be ordered from both Kemi and Tornio, but would be also quite expensive.)

Thus it is difficult to visit this place by accident or as a side attraction during a larger trip, and I've been planning a trip to this national park since last year. And thankfully, it did come true when on a hot July weekend we took a trip to Kemi and from it to the Bothnian Bay National Park with Annika.

This destination has some things in common with Ulko-Tammio of the Eastern Gulf of Finland National Park. Both these national parks are tiny by land area, little visited, and have only a few public tours there every summer. Both are very close to the sea borders of Finland, bordering Sweden and Russia respectively. The towns from which tours depart, Kemi and Kotka, are also in my opinion somewhat similar in spirit and appearance (although Kotka is significantly bigger). Islands themselves however are very different in their nature and appearance, and Ulko-Tammio is of course a lot closer to the cities of South Finland or to St. Petersburg.

Getting There

As usual for more difficult destinations, let's talk a bit more about the arrival options. A good place to begin is the official web page of the national park.

As with most of island destinations in Finland, transportation is handled by private companies which may appear, go out of business, or change their destinations and schedules every season, and this information is only valid for 2021. This year for example the boat from Tornio, Lady Carin (webpage in Finnish), is not running due to corona, even though as of July 2021 there are (again) very few actual corona restrictions within the country. But the other option, Perämeren Jähti from Kemi, is available and is actually much more cool because the Jähti is actually a sailboat! It can and does of course also move under motor power so a lack of wind is not a problem (a storm is, though, like for any other archipelago tour). Its schedule and prices can be seen here, in Finnish, and places can be booked either by email or online here. The latter page is in English but does not have an actual schedule and simply shows days with no trips as "reserved", so it's better to check schedule from the first page. And yes, we're again in the mostly-domestic Finnish tourism sector territory, so prepare to use Google Translate for the webpages and, unfortunately, to miss most of the tour contents if you don't understand spoken Finnish. (The crew do speak English and can answer questions and explain some particular things of course.)

Be aware that both Lady Carin and Perämeren Jähti also offer tours to some other local islands, but only islands of Pensaskari and Selkä-Sarvi belong to the Bothnian Bay National Park proper! Even if you are not interested in visiting the national park specifically, its islands are probably still more interesting than the closer ones. In the national park there is of course quite a few other islands too, but only Selkä-Sarvi and Pensaskari have actual harbors large enough for anything bigger than a small motor boat. Selkä-Sarvi is the bigger and the more interesting island, and the one that we visited ourselves. In the season of 2021 there are only 3 tours to Pensaskari and 2 tours to Selkä-Sarvi by Perämeren Jähti. And some of them actually take place on Fridays and are thus inconvenient for working people. We therefore used pretty much the only our possible option for visiting Selkä-Sarvi in the whole of 2021, yay! We booked a place about 10 days beforehand, thankfully there was still enough places. The ticket price for adults was 80€, which is of course not particularly cheap. This includes transportation there and back, guided tour (with some free time afterwards) and a basic lunch (salmon soup and coffee). The entire thing basically takes the whole day (9-18). Pensaskari tours are shorter and a bit cheaper at 70€.

I personally can give a special recommendation for Perämeren Jähti; it absolutely was the best archipelago tour that I ever had — and I visited many Finnish islands all the way from Ulko-Tammio to Selkä-Sarvi. The crew is really just the best, they all seem to be extremely enjoying their jobs, especially the captain and the current owner of the ship, Olli Ahonen. (At some point closer to the end of our tour he took a call and then shouted to us all that he just became a grandfather the second time, and we all clapped to him.) The first mate, don't know his name unfortunately, was also full of stories, which I thankfully could also understand at least somewhat with my own Finnish. They all appear to be natives of the Kemi area and know the sea, the local fishermen here and everything else about these lands better than anyone. The very reason I'm writing this post in English too, even though at the moment I generally stopped doing this, is to make possibly more people aware of how glorious Perämeren Jähti is!

Perämeren Jähti departs from the inner harbor (Sisäsatama, address Rantabulevardi, Kemi) in Kemi center, and Kemi center is slightly over a kilometer across and is easily walkable. Kemi itself can be reached both by train and by various buses fairly easily; all trains going to Lapland (Rovaniemi, Kemijärvi, Kolari) stop at Kemi. Thus a car is completely optional for visiting this national park, yay! Travelling from Helsinki to Kemi by day train takes 7-8 hours. Night train options are also available and in theory allow travelling from the south to Bothnian Bay National Park without any hotel stays, if desired. And if not, then Kemi has at least 3-4 hotels in the center bookable through normal channels like Booking.com.

Lady Carin on the other hand used to depart from Puotikari harbor, close to the big freight harbor of Tornio (Röyttä), address Selleenkatu 181, Tornio. It is 12 km away from Tornio center with minimal bus connections (two buses on weekdays), and Tornio itself is a bit more difficult to reach by public transport; only night trains to Kolari stop at Tornio, at inconvenient times of day. Thus if trips by Lady Carin become available in the following seasons, it would be much easier to get to that harbor by car if possible.

If you do travel by car, there isn't really anything special to tell. Parking is free and unlimited in both harbors.

The season for boat trips to the national parks lasts pretty much just 1.5 months in July-August, but there is also an extreme option: skiing there in winter, on the Bothnian Bay ice! The distance would be 6-18 km depending on the island. Care must be taken to avoid the Kemi and Tornio shipping lanes, which are kept open in winter with icebreakers; because of those Selkä-Sarvi archipelago in particular can be reached by ski only from Tornio. Ice season on the Bothnian Bay is long and the ice gets rotten only closer to May; see current ice conditions page and in particular the maps which are updated daily during the ice season. There are no official maintained tracks and the whole thing is at your own risk of course, but at least it is considered safe enough to be mentioned on the official page at the bottom.

That's pretty much it. More up to date links to transportation services, including water taxis, are available at the official page. I recommend the Finnish version of that page (that I linked here), as it is more complete than the English one.

Our Trip

We decided to go to Kemi by train this time. From Tampere, where we currently live, to Kemi it is about 600 km by road, and I was not especially eager to do such a drive for a weekend trip; the train was also faster, although with the time it took to get to the railway station in Tampere by a local bus, and then walk from the Kemi railway station to the hotel, time savings got quite minimal. Tickets for two were somewhat more expensive than gas would have been, but not hugely so. In the end I don't know if it would have made more sense to go by car. I still quite like visiting cities by train, it feels sort of more "real" this way, when you cannot just hop into your car and drive anywhere you like at any point.

We left on Friday immediately after work (the train left at about 16). In Kemi we booked the Scandic Kemi for two nights, which actually was a bit cheaper through their own website than through Booking.com. Even though I travel around the Nordics pretty much all the time, this was the first time ever I actually stayed in one of the biggest hotel chains; we decided it would be fun for a change and it wasn't that expensive this time (97€/night). (Generally I prefer small hotels/motels or AirBnB-like apartments, often on the outskirts of the cities or outside them; those are cheaper, usually spacier, have kitchens or at least microwaves for eating your own food, and the location doesn't matter too much if you travel by car. Unless you want to drink in bars in city centers and then walk back to your hotel, but I usually don't.)

1. After quickly changing trains in Oulu we arrived to Kemi at 21:20 and found a pizza place to eat (finding something to eat at a Finnish city of that size after 21:30 is no easy task! Plenty of places to drink, of course). Kemi is a really lovely town, in my opinion. It is one of the last so-called "old towns" in Finland, founded in 1869 by the order of tsar Alexander II along with a few others of which only Iisalmi in the end got city status. New cities were one of the measures taken by the Good Tsar to revive the economy of Russia and its Grand Duchy of Finland in particular after the Crimean War of 1853-1856. The new city got a characteristic grid plan, and nowadays quite a bit of nice wooden architecture still remains from the 19th century. The city gets its name from Kemijoki, the biggest river of Lapland and pretty much the entire Finland (Vuoksi in Imatra has bigger flow, but only a very short part of it remains on the Finnish side of the border), blocked by many hydro power plants; however Kemijoki mouth and estuary is located to the west from the actual city and this time we didn't see the river at all.

Kemi quickly got prominent as an industrial city, originally due to sawmills at Laitakari, Karihaara and Veitsiluoto areas outside the city proper. To these days the descendants of these sawmills exist, although the biggest news for Kemi in 2021 has been the coming closure of the Veitsiluoto paper mill. The population of Kemi peaked in the 1960s at almost 30,000, and lowered by now to some 20,000.

Kemi is pretty much the most beautiful city of Finnish Lapland, and yes, administratively it already belongs to Lapland (Lappi). Kemi and Tornio area is known as Sea Lapland (Meri-Lappi), and is quite distinct from the rest of Lapland; these cities are considerably older and better preserved (especially Kemi) than inland ones, and the coastal areas are almost completely flat and lack characteristic Lapland hills and fells. Another name for this area is Länsipohja, "Western Bottom", which comes from the Swedish name Västerbotten meaning the same. In the days of the Swedish Empire the border between Sweden proper and its Finland area (in practice meaning for example different dioceses: Uppsala and Turku) was considered to be the Kemijoki river. The lands west of it were Västerbotten or Westrobothnia, "West Bottom" and east of it lay Österbotten or Ostrobothnia, "East Bottom"; Sea Lapland was considered to be a separate area. Nowadays it is (at least informally), both on Sweden and Finland sides of the modern border, but the slice of it that used to belong to Sweden proper before 1809, between Kemijoki and Tornionjoki rivers, is now still occasionally known in Finland as Länsipohja.

I visited Kemi before once, in May 2018, but never wrote about it then. In this trip I didn't take many pictures of the city and this post is more about the national park, but we'll still see a bit of Kemi. Sarvi-Selkä island to which we are heading also administratively belongs to Kemi municipality.

2. Empty evening Kemi streets. Kemi is easily recognizable by its concrete sidewalks in the center, a feature that I don't really remember seeing in any other Finnish cities, not to this extent at least.

3. And our Scandic awaits.

4. The morning of the national park trip! Our ship departs at nine in the morning, and after the hotel breakfast we're walking to the harbor along the coast. This is one of the small boat harbors along the way, with a rescue boat to the right.

5. This work of art with names of various ships and boats is named Majakka (Lighthouse). At night there is apparently a light shining inside. We couldn't really see it; this being Lapland, at this time of year the day in Kemi lasts 22 hours 24 minutes.

6. The Inner Harbor (Sisäsatama) gets busy on summer evenings, but on Saturday morning it is still quite empty. The masts of Perämeren Jähti are visible to the right. The woman checking the passenger list was interrupted by a horsefly, from which she had to run away several times, accompanied by a hearty laugh of everyone present. This set mood for the trip nicely already :)

And yes, horseflies! These creatures, called paarma in Finnish, aren't quite as common or numerous as mosquitoes, but their bites can be a lot nastier. Unlike mosquitoes they don't really mind the sun, and can quite enjoy sea shores in particular. Like mosquitoes they generally are more common farther in the north, and the islands of the Bothnian Bay National Park are in fact a prime location for them. So, yes, be ready to meet horseflies. Personally I wasn't very troubled by them (it seems they are not interested in me for some reason), but I did see quite a few on that day at least.

7. And off we go, after an introductory speech (and a small safety briefing) by the captain. Kemi is one of the surprisingly very few Finnish coastal cities which actually have unobstructed sea views right in the center; the only other ones are Helsinki and Kotka. The island of Selkäsaari, to the left in the picture, does obstruct some of the view but not all of it.

8. The day was rather hot and nearly windless, so sails were unfortunately of not much use, but the crew still raised them when we left the harbor. At one point they shut down the engine, and apparently under sail power (and in unusual silence) we were drifting at some 3 km/h, according to my GPS.

9. I don't really remember much about sailing ship rigging and sails, although as I kid I reread an old book on the subject a lot.

10. The Kemi archipelago. Bothnian Bay islands are sparse, very flat and more sandy than rocky; while they might have a lot of small boulders strewn around, there are usually no large rocky areas, hills and cliffs. This contrasts to the geography of both the Finnish mainland and most of its more southern archipelagoes.

The Bothnian Bay is rising from the sea at pretty much the same speed as Kvarken area farther to the south, near Vaasa: 8-9 mm per year. This happens because of postglacial rebound, as glaciers completely covered this area during the last ice age, and now, after they've melted, the bedrock underneath, pushed down by their great weight, is very slowly springing back. This means that all these islands are fairly young, less than 1000 years old certainly, and are still rising. Their area is accordingly expanding, and the coast is slowly becoming dry land, with small bays eventually becoming cut off into so-called gloe lakes (kluuvi), giving birth to some fairly unique small ecosystems.

Due to this postglacial rebound Kvarken strait, dividing the Bothnian Bay from the Bothnian Sea, is expected to rise completely from the water in a few thousand years (outpacing also the sea level rise due to global warming), turning into a land isthmus. The Bothnian Bay is thus fated to eventually become a lake, significantly bigger than Ladoga which is the biggest European lake at the moment. Even now however the bay has a rather lake-like character in practice. This is the shallowest part of the Baltic Sea (average depth about 40 m), and the water here is nearly fresh, with only 0.30-0.35% salt content, up to three times smaller than in the Baltic Sea proper (south of Åland). Bothnian Bay covers up with ice completely or nearly completely even in warm winters, with ice thickness reaching a meter or more near Kemi and Tornio, and thus Finland and Sweden need to operate icebreakers for a good part of the year. Other major ports on the Finnish side are Oulu, Raahe and Kokkola, and on the Swedish side the most significant one is Luleå.

11. Passing close by the Kuivanuoronkrunni island (Finn. Dry Rope Shallow?). Krunni is a word specific to the Bothnian Bay area and often used here in island names, coming from Swedish grund, meaning "shallow". This island is one of the few still having an active fishermen camp which looks quite traditional. Their equipment is visible here, and a net marked with flags is in the water behind the island.

Professional fishing in Kemi and on the Bothnian Bay in general is by now a very niche occupation, but still exists. It is a rather marginal area for fishing in general; fishing volumes in the Bothnian Sea for example are 25 times greater (statistics from 2020). More salmon is being fished here than in other areas, but that still means only 83 tons in absolute numbers; overall 2350 tons of fish was caught here in 2020. About half of that was herring, which is by far the most important commercial fishing species of the Baltic Sea in general.

12. Sailing on! Perämeren Jähti takes about 30 passengers, although they all more or less have to be seated on the deck. There is a "restaurant" below deck (where they served salmon soup later while at the island, and also sell beer and cider) but its area is rather small; its walls are lined with sleeping bunks behind curtains.

You might think that the word jähti means "yacht", but it does not; that would be jahti in Finnish (without the dots above a). A jähti is/was a local name for a ship class known elsewhere in Finnish as kaljaasi and in English as galeas: a smallish, typicall two-mast trade vessel on the Baltic and North Sea, used in 17-20th centuries. The name galeas in turn should not be confused with galleass, a kind of a large military galley (a ship with both sails and oarmen) used in Europe the 16th century. The names are undoubtedly related but the ships don't really have anything in common.

Jähti was built in 2007 by some employment support organizations in Kemi and Rovaniemi, supposedly based on old galeas traditions of the 19th century, insofar as possible these days. It changed owners several times and stood idle for long periods at a time; it is not particularly easy to operate such a ship profitably, especially in Kemi where tourist numbers are not going to be especially impressive. Still for the people of Kemi Jähti is a point of particular pride, and no one here would want it to end up being sold "to the south". In the end a few years ago it was bought out by its current captain, and I really hope business is going reasonably well for him.

13. Now we crossed the Tornio shipping lane, marked by pretty large buoys, and are approaching the islands finally. The Jähti is fairly slow, even using the motor, and the trip in one direction takes 2.5 hours. The island to the left and in the foreground, appearing bigger, is Maa-Sarvi, and our Selkä-Sarvi is the one to the right with a lookout tower. Names mean "Land Horn" and "Sea Horn", perhaps referencing the position of the islands relative to the mainland and the open sea. Selkä in Finnish in this context means a large open water area (can be not just sea but also a large lake), and this is pretty much the last island of the archipelago; farther to the south the Bothian Bay stretches completely open.

The lookout tower used to belong to the border guards. I haven't really been able to find much information about the border guards presence on the island, and neither I remember any relevant details from the tour. We are indeed less than 2 km from the Swedish border, and a few Swedish islands of similar size and appearance can be easily spotted.

The sea border guard station at Röyttä, the freight harbor of Tornio, was shut down in 2004, and probably the Selkä-Sarvi border guard hut and tower were closed at the same time. (Although in corona times crossing the sea border stopped being freely allowed again...) The tower doesn't appear to be particularly old or damaged, but the door to the ladder is locked. It is possible in principle to climb over the door and a few people tried that, but while we were gathering our courage for that it was already time to go back.

14. Here we are and finally a good look at Jähti itself! Unfortunately there was no way to take a picture with sails raised, as the crew put them down again when we were approaching the harbor at the northern tip of the island. It is a pretty cramped-looking harbor; there were already a few private boats which brought other people to the island.

15. Now it's official: all 40 national parks visited! The national park logo features a tern bird and a primrose flower. This rare primrose species is called ruijanesikko in Finnish. Ruija is the Finnish name for Finnmark, the northernmost part of Norway, and indeed ruijanesikko usually grows there on the Arctic Ocean coast; on the Baltic Sea it is encountered in only a few places, including the islands of this national park. I don't think I saw the flower, but terns are certainly very common here.

16. The island is 150-300 m wide but over a kilometer long. A nature trail runs along its length, and that's where we immediately went to. The landscape of Selkä-Sarvi alternates between these sandy and rocky parts, in places overgrown with juniper, and low but fairly thick deciduous groves. It is allowed to walk outside of the trail in general, but walking in some coastal areas is forbidden in bird nesting season (May-July).

17. Some old fishermen huts also on the northern tip of the island.

18. An improvised navigation sign, showing perhaps the way between Selkä-Sarvi and Maa-Sarvi. The existing shipping lane to Selkä-Sarvi harbor is mostly unmarked.

19. The trail branches a bit in one place so that you can have a look at this sundial. The digits carved into rock are nearly invisible though (certainly invisible on this picture, unfortunately), and so is the year when the sundial was constructed, 1798.

20. Swedish islands on the horizon: Sarven Riskilö to the left, with a fishermen camp visible, and Sarven Kataja to the right.

As a matter of fact Sweden has its own marine national park here on their side of the border, although considerably farther from it (islands in the picture are not a part of it). That national park is called Haparanda Archipelago National Park (Haparanda skärgårds nationalpark), after the Swedish bordertown of Haparanda. The main island of the national park is called Sandskär, is considerably bigger than Selkä-Sarvi, and boat tours there from Haparanda harbor appear to be much more common. Well, the page does say helpfully: "This day trip to Sandskär is subsidized by the county government". We don't have such subsidies in Finland as far as I am aware. Good for Sweden! Anyway I haven't been to Sandskär myself, nor do I plan to for the time being. Right now my passport is still in the process of being renewed at the Russian embassy in Helsinki (it takes several months to do it), so I cannot leave Finland at all.

21.

22. Towards the southern tip of the island. The island has reservable huts (vuokratupa) bookable for a fee both on the northern and the southern tip; both also have saunas. The southern tip also has an open wilderness hut (autiotupa) freely available for use. Since regular trips to the island are so rare you would need an own boat or a water taxi trip to use those.

This Kokko hut (built in the 1930s as a fishing net storage, later converted for residential use) is also used in summer by the shepherd volunteers. As of 2021 Metsähallitus (Forest Administration), the Finnish state enterprise responsible for managing national parks and other state lands, maintains 15 farms around Finland where sheep are brought to in summer (from various private owners), and anyone can live there and care for them for the modest price of 400-500€/week. Yes, the idea of living in some old hut without running water or electricity and just watching over sheep and enjoying nature is so popular that Metsähallitus not only charges a lot of money for this, but also gets almost 15,000 applications per year! The actual shepherds are chosen among applicants at random, and of course you can apply for specific times and a specific farm. Details can be read here (in Finnish) if you're interested. The Selkä-Sarvi location is apparently among the least popular ones also due to difficulty of reaching it (you would have to arrange your own transportation to the island, this is not included in price). Unfortunately we didn't see the actual sheep, although we really hoped to; nearly the whole island is their pasture here, and it's not that difficult for them to wander from sight.

23. Spending a week on the island might be tricky also in regard to drinking water. This well in the middle is the only water source, but the sign says the water quality is untested and the national park website outright recommends against drinking it.

The pole to the left, with the remains of a barrel up on it, is also a navigational sign of sorts; together with a smaller pole farther away it used to point to the direction of the nearby herring fishery. The pole was put up by the fishermen no later than the 1930s, but fell in a storm in 1982; the modern one is a replica.

24. View to the northeast. The horizon can be seen faintly; the white spot left of center is the town hall in Kemi center, by far the highest building there. Towers and hills barely visible around it belong to the Elijärvi mine, some distance behind the city. The mine, opened in 1968, started as an open pit mine but currently it is the biggest underground mine in Finland. It produces chromite ore which is then used by the stainless steel refinery in the nearby Tornio. Both the mine and the refinery belong to Outokumpu company, and are the biggest non-timber/paper-related industrial sites in Sea Lapland.

In the left of the frame the Pajusaari pulp mill of Metsä Fibre is visible. This factory is going to be completely replaced by a new bioproduct mill, a 1.6 billion euro investment, which got finally greenlit in early 2021. In the right of the frame is the Ajos harbor of Kemi, with wind turbines nearby visible.

25.

26. The huts closest to the southern tip of the island are privately owned by Ajos and Alatornio fishermen associations from Kemi and Tornio respectively. We actually saw some fishermen there, whom our captain of course seemed to know well.

27. Some drowned guy's boat, as we were told.

28. Back from the south to the north of the island. The unpainted building is the Ailinpieti hut (Ailinpietin kämppä), named after its first owner, Arvid Ailinpieti. This is one of the oldest if not the oldest remaining building, dating from the 1860s. It was used by fishermen, Ailinpieti's descendants, up until the 1960s, and was restored by Metsähallitus when the national park got established and the hut passed into state ownership. Nowadays it is basically a museum building, open for visitors although there's not really anything inside other than curious inscriptions cut into its walls over decades. The red building to the right has a small exhibition of various fishing implements.

Few buildings overall remain on Selkä-Sarvi these days, but it used to be quite a lively fishing village in the 19th century and also for a time in the 1930-1940s, following the Shortage Time (pula-aika), which is what the Great Depression was known in Finland as. The fishermen were mostly the natives of Hailuoto, a quite large (and still very much inhabited) island off Oulu coast. Up to 300 people lived on Selkä-Sarvi at most, although as I understand this kind of settlement was seasonal. The whole thing likely was quite similar to Tankar, an island in the southern Bothnian Bay off Kokkola coast that I wrote about half a year ago. Tankar however still has most of its huts intact (and also a lighthouse), while Selkä-Sarvi got nearly deserted. Most of the buildings here didn't survive due to mostly quite temporary construction methods used, and the construction materials (timber brought from the mainland) being reused elsewhere.

How old the human presence has been active on Selkä-Sarvi overall is not known precisely, but most likely from the 16th or 17th century. The rate of the postglacial rebound means the habitation here cannot be too old; none of these islands even existed a thousand years ago.

29.

30.

31. One of the more densely wooded areas.

32.

33. Apparently this basement was built (before the national park was established, presumably) by some guy who was really eager to have a hut here and started before he applied for a building permit — which later got rejected.

34.

35. The pad in front of the rest of the duckboard path is a visitor counter, as I understood. I haven't seen such visitor counters before, usually optical ones are used. The captain joked that we should run across the pad several times so that Metsähallitus sees the increasing visitor counts and the national park gets more investment.

36. Annika went for a swim (the water was fairly warm despite this being a smallish outer island in the sea) and to the sauna, which had been heated by the ship's crew, and I just enjoyed the island for a little while more. Then we went to the ship for the salmon soup lunch, and by that time we were leaving already. Four hours on such an island feel seems a long time, but it didn't really feel like it.

37. Outokumpu stainless steel refinery and the Tornio harbor at Röyttä. And more wind turbines; the Bothnian Bay is a popular place to build them.

38. Far to the southeast we could see the Keminkraaseli lighthouse, which is the northernmost lighthouse in Finland and the closest one to the Swedish border. The lighthouse was built on a small rocky skerry in 1937, and is now automated like all other Finnish lighthouses. It is not a tourist destination and there are no regular tours there.

The word kraaseli, like the aforementioned krunni, is another one commonly used for island names on the Bothnian Bay, and similarly comes from Swedish, in this case from the word gråsäl, meaning "gray seal", presumably because those seals enjoy hanging out at these islands. Gray seals are relatively common in the entire Baltic Sea, including the Bothnian Bay; common enough that they are still legal to hunt in Finland (with a license of course). I have never seen a seal in the wild myself, not on this trip either.

39. And the is the Kemi outer harbor at Ajos; we were going back to Kemi using another route, close by Ajos. The harbor specializes on liquid fuels, chemicals, timber and containers. The total freight volume of Kemi harbors in 2020 (including also the much smaller Veitsiluoto harbor) was 1.1 million tons for export and almost 1.9 million tons for import.

40. Close by Ajos we saw not only fishing nets, but also a fishing boat in action!

41. Part of the harbor up close.

42. Veitsiluoto (Finn. Knife Island) paper mill visible behind the isthmus connecting Ajos to the mainland. This is the northernmost paper mill in the world, established in 1932 and owned by Stora Enso company. Unfortunately Stora Enso announced in April 2021 that the mill is to be shut down permanently this year. Although, as I mentioned before, the same year Metsä announced the building of a bioproduct mill in Kemi, this won't outweigh the Veitsiluoto closure; more people (550) will be laid off here than will be hired for the Metsä mill. Moreover paper mill jobs are notoriously specialized and wouldn't really transfer to another kind of industry.

The decision was terrible news for Kemi, but was not altogether a surprising one. The world demand for paper is steadily lowering, and the remote work boost brought by the corona pandemic is only making it faster. Stora Enso is closing another paper mill in Sweden at the same time. Last year UPM company shut down the Kaipola paper mill in Jämsä, another small town, that one in Central Finland; 448 people lost their jobs. Kaipola is the biggest paper mill ever shut down in Finland to date, but the entire list is long enough to have its own page in Finnish Wikipedia.

In general though even smaller cities seem to be able to more or less adapt to such blows; I remember reading that Kajaani or Voikkaa (Kouvola suburb) for example seem to have more or less completely recovered in the 15 years or so that have passed since their paper mills shut down. Of course in the long term Kemi is still a dying city, but that is true of pretty much all of the smaller Finnish cities and that trend is not really going to change.

43. Well, anyway, here we are, approaching the inner harbor of Kemi. Looks not bad for a dying town!

44. A few more pictures from Kemi, not capturing even all the main sights but still. The old warehouses on the shore, where nowadays mostly various bars are located. I seem to remember that the "seaside residence of Santa Claus" was around here too (his normal office, as we all know, is in Rovaniemi, the regional center of Lapland), but I didn't really notice it this time.

45.

46. Lovely evening Kemi.

47. Although not everyone thinks so for some reason.

48. In the evening we went to one of the bars for a drink, althuough rather briefly, and on Sunday we had a lot of time to waste; our train was leaving at around five in the evening. So we stayed at the hotel as long as was possible and then went for a walk. The weather was hotter than the previous day, but we still managed to walk to Kiikeli, a small forest west of the city center on the Bothnian Bay coast.

49. The Bothnian Bay is my favorite sea (or, my favorite part of Baltic more precisely, along with Kvarken).

50. Kemi center as seen from an observation tower at Kiikeli coast. Kemi has in principle quite a few tourist sites (historical museum, the "snow castle" which is partially preserved even in summer, jewel gallery) but for some reason every single one of them was not actually open on Sunday.

51. In Kemi center again. The city hall, the white tall building in the background, is the local landmark. It was built in 1940 and is notable as the building that the Germans could not blow up. The Lapland War of 1944-1945 was the conflict between Finland and Nazi Germany when Finland, having concluded peace with the USSR and thus the Continuation War of 1941-1944, was forced to remove from its territory troops of its former ally: Germany. German troops had been attacking the USSR from the northern half of Finland, and there were plenty of them still remaining in Lapland.

The Germans naturally did not really want to leave on good terms, and the war ensued. It claimed relatively few lives (less than 2000 on both sides combined) but material destruction was massive, as retreating Germans destroyed all villages, towns, roads and bridges behind them. Rovaniemi and pretty much all other inland Lapland towns (if you could even call them towns at that time; even Rovaniemi was in truth quite tiny) were almost completely destroyed and had to be rebuilt after the war. Kemi and Tornio, the Sea Lapland cities, were however the first places to be retaken by Finland, and thus were mostly spared the destruction. In Kemi Germans tried to blow up just the city hall, but despite severe damage (see picture in Wikipedia) not only it didn't collapse, but could be completely repaired after the war.

52. Well, goodbye Kemi!

53. And the train is finally taking us... no, not to Kuopio as the display says; we're changing trains again in Oulu to go to Tampere direction.

The final Finnish national park is claimed now. What next? I have only a handful of Finnish towns (all of them really small of course too) remaining... And of course there are at least a few longer hikes to try in the north. But generally my Finnish exploration project is nearly complete.