After an over three month delay I'm finally making a next post in the Vaasa series (I'm somehow very bad at consistently writing any kind of series, and much prefer standalone posts about some random places no one knows or visits; but visiting Kauhajoki in the good old South Ostrobothnia, not very far from Vaasa, helped). Today we'll be looking at areas close to Vaasa center, but not on the very central streets. The previous post in this series is Vaasa Center. Part 1, and if you haven't read that one either I would recommend to start with Vaasa, Kvarken, Korsholm. Overview, which is pretty much my love letter to Vaasa and has the best pictures and best overall description of the whole region in it.

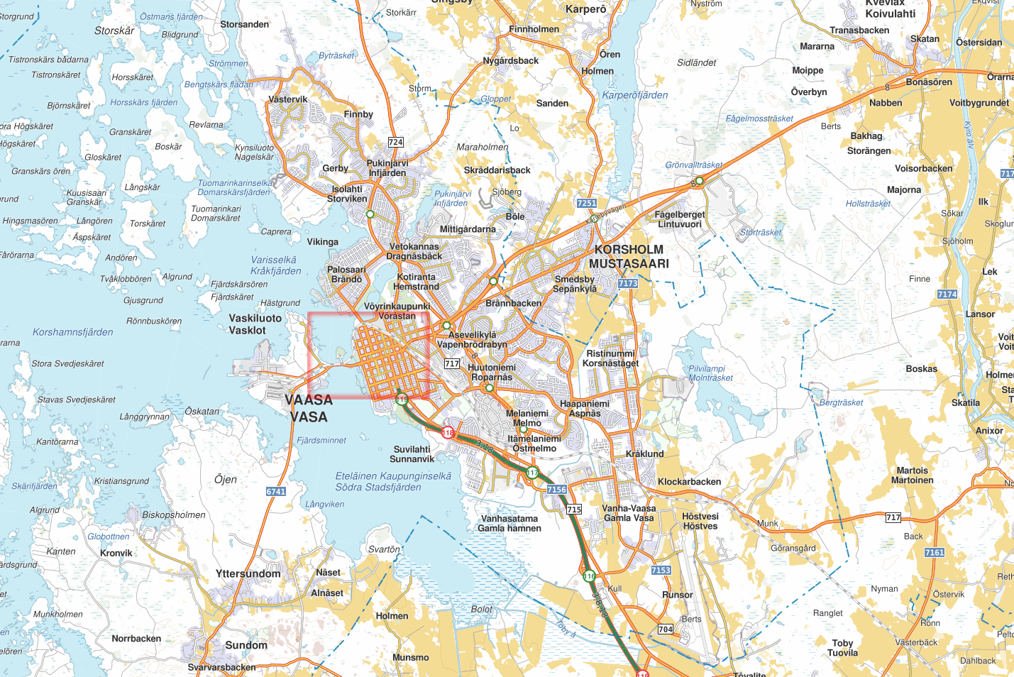

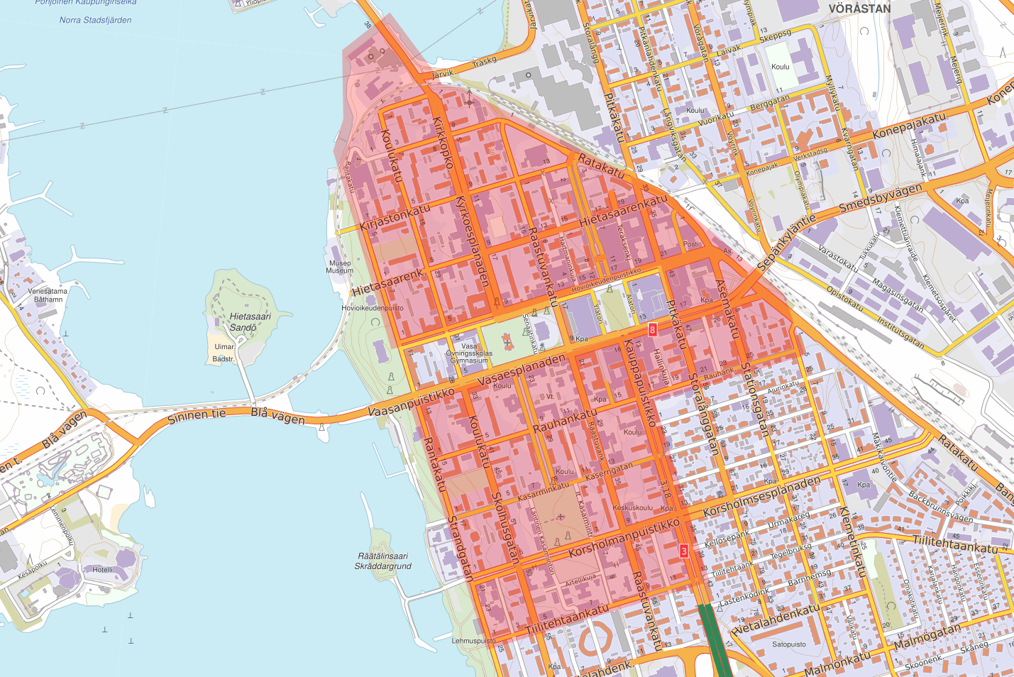

Appoximate area covered in this post:

Let us start with the railway station and then go in a roughly clockwise direction. As with all posts in Vaasa series, the actual pictures were taken over two years in all kinds of seasons and weather conditions.

1. Vaasa railway station was built in 1883 along with the entire Seinäjoki-Vaasa rail section. The original wooden building by Knut Nylander is still in use, as is the case for many Finnish cities even of considerable size; although most of is rented out for various businesses by now. We covered Vaasa transport connections overall in one of the previous posts; suffice to say there are many trains, although only in Helsinki direction (via Seinäjoki and Tampere), and a train would generally be the transport of choice for someone travelling between Helsinki and Vaasa (about 3.5 hours trip). At the same time there are no suburban trains, as in other Finnish regions, and long-distance trains don't stop at most small town stations.

2. Same on December evening.

3. Station interior still features a "Nikolainkaupunki" sign (Finnish name of the city in 1855-1917).

4. As is the case in many Finnish cities, the bus station in Vaasa is now immediately next to the railway station, literally across the platform. The glass building on the right serves as a bus station building as well as a stair/elevator to the road overpass above. The bus station has connections to nearby cities, although mostly not especially frequent or convenient. Onnibus buses, which I'd say are currently in practice the most important long-distance bus chain in Finland, offer both a relatively direct connection to Helsinki (via Seinäjoki and Tampere, as with trains), and a route Helsinki-Turku-Pori-Vaasa-Oulu going along all west coast cities.

5. An interesting event that I saw in December 2018 was a visit of a museum train from Haapamäen Museoveturiyhdistys ry (website in Finnish only) (Haapamäki Museum Engine Association). These guys have quite a bit of museum rolling stock at the old major junction station in Haapamäki (which is must less important nowadays), and operate museum trains on various occasions on various parts of the Finnish rail network, more often than not in places where there is no passenger service anymore. This train with Tv3 steam engine and old wooden passenger cars for example coursed between Vaasa, Vaskiluoto station close to the seaport, and Laihia station at the eponymous town close to Vaasa where trains don't stop anymore. I wrote a more detailed story about this train and a trip on it earlier.

6. Boarding the museum train.

7. The fanciest looking Vaasa hotel, Astor, across the street from the railway/bus station.

8. A much less fancier hotel is Omena (Finn. Apple) very close by at the end of Hovioikeudenpuistikko (Finn. Court of Appeal Parkway). These are often among the cheapest hotels in the major Finnish cities (although they operate only in a few such cities), with fully automated check-in. I don't think I've ever actually stayed in one of those myself. Omena is located in the Vaasa central post office building. I remember making my first change of address notification there in December 2017 (these can be made online, but I didn't have access to Finnish online state services yet, so I did it the old fashioned way by filling a form and mailing it in a prepaid envelope at a post office). However last year, if I remember the news correctly, this post office was closed down. This was as far as I know the only "real" post office remaining in Vaasa; post office functions are now overwhelmingly often shared by small grocery stores, and a dedicate post office is a very rare thing these days.

9. Ab Wasa Yllevarufabrik — Oy Waasan Villatavaratehdas (Finn./Swed. Vaasa Wool Factory) old building, very close to the railway/bus station. The factory operated from the 1900s to 1969; the building has been converted for residential use subsequently.

10. Asemakatu (Finn. Station Street) buildings.

11. A Finnish-language Vaasa city theater on Pitkäkatu (Finn. Long Street) — Rauhankatu (Finn. Peace Street) intersection. I have never been in a theater there, neither in this one nor in the other Swedish-language one.

12. Pitkäkatu. This Pikku Quattro pizza was rather decent.

13. Some people were actively supporting the local Vaasan Sport ice hockey team during the national championship. Some store on Vaasanpuistikko (Finn. Vaasa Parkway) close to the central square.

14. Kauppapuistikko (Finn. Commerce Parkway) is the street where cars arriving from Seinäjoki/Pori/Tampere/Helsinki direction enter the center.

15. A parking meter on Kauppapuistikko. It is a pretty short walk to Vaasa center from any place outside the tolled parking area (about 1 km in diameter at most); nonetheless, Vaasa has four parking zones, with street parking costing from 2.20€ to 0.50€ per hour. This is the 3rd zone so it's 1.00€ per hour here.

16. Vaasa ends pretty abruptly with Kauppapuistikko just turning into a motorway, which stretches for 12 km until turning into a regular road (National Road 3). Actually a roundabout is now being built in this place (or maybe it's already finished); mostly for easier access to the Vaasa hospital, but also as a result it would be a natural border of the city in a way.

17. A Baptist church on Raastuvankatu (Finn. City Hall Street).

18. Parallel to Kauppapuistikko is Kirkkopuistikko (Finn. Church Parkway). The northern part of it serves as the main road to Palosaari area but the central part, connecting the Lutheran and the Orthodox churches, is very quiet. The Lutheran church (the main church of Vaasa) is in the background.

19. The water tower can be seen close by this street. I already told about it in the previous part.

20. Winter Kirkkopuistikko.

21. Swedish-language Vaasa gymnasium (high school). There is also a Finnish-language one; Finnish-language ones are called lyceums (lukio).

22. A school on Kirkkopuistikko.

23. A monument to Carl Axel Setterberg (1812-1871), the chief architect of modern Vaasa post-1852 fire. He designed quite a few notable buildings of modern Vaasa as well; we already saw a few of them in the previous part. Setterberg, a Swedish (not just Finnish-Swedish) man from Södermanland County who had previously worked as the chief architect of Gävleborg County, spent the rest of his life in Vaasa and died there. Setterberg's master plan for Vaasa can be seen on the monument.

24. And this is the Orthodox church in Vaasa, the St. Nicholas church. It was designed by Setterberg, same as the Lutheran church on the other end of the parkway from it, and built in 1862.

The reason Vaasa needed this church at all was presumably its importance as an administrative and military center in the Russian Empire era. These days the church is probably extremely quiet; I literally never saw anyone entering it (not that I visited this area all that often, of course). Vaasa Orthodox parish has only about a thousand members, although it covers the fairly vast area of the former Vaasa County, which included modern Coastal Ostrobothnia, South Ostrobothnia and Central Ostrobothnia regions. Orthodox Christianity in Finland is relatively strong in Helsinki area (with many Russian immigrants) and in the East (with its ties to the Orthodox Russian Karelia); in other parts of the country it is very insignificant.

25. St. Nicholas church stands in the middle of a fairly empty small park, and in winter there are ski tracks around it.

26. Around the church are a few blocks of very nice-looking wooden barracks, one of the best preserved such barrack areas in all Finland.

The space for the barracks around an Orthodox church was reserved by Setterberg in his Vaasa plan, but they got actually built only somewhat later, in the 1880s, designed by August Boman, same architect who built the barracks in Oulu and Mikkeli. Contrary to what I myself had always assumed before researching the subject for this post, the barracks were initially meant for a Finnish (not Russian) unit. In 1874 conscription was introduced in Russia and in 1878 in Finland, its autonomous province. Eight infantry battalions were established in Finland then (before that the Grand Duchy of Finland didn't have an army of its own). The 3rd Infantry Battalion was quartered in Vaasa and drafted from local Ostrobothnian men. Finnish army was however still kept at a fairly modest strength; it never exceeded half of the numbers of Russian troops quartered in Finland.

In 1901, during the first wave of the Russification of Finland (when Russia moved to severely restrict the previously very wide Finnish autonomy; known as sortokausi, "oppression period" in Finland), Finnish army was however abolished by Tsar Nicholas II, and barracks in Vaasa among others came into Russian possession. Russia quartered its own troops there until the Finnish independence declaration; at that time, Finnish White Guards occupied Vaasa on 28.1.1918, in the first days of the Finnish Civil War, and Russian troops were driven away, not just from these barracks near the church, but from a few other barracks in other parts of Vaasa too. This was not an entirely bloodless operation; two Finnish White Guards and 15-20 Russian troops died in the skirmish. The early control of Vaasa and the strong local support allowed the Whites to move their government there, as Helsinki actually remained a Red citadel for a few months. Subsequently the barracks served as a prison camp for a while; up to 2400 Russian troops and up to 900 Finnish Reds were kept there (these two groups were generally completely unrelated). Up to 110 people died mostly from executions, also a few cases of disease, of them 90 Russians. Executions were not an official policy nor were they actual court verdicts but rather were given out as personal acts of revenge by the locals (for example there were cases when the local archipelago smugglers, killed by Russian coast guard in the previous years, were thus being avenged; Russian coast guard had been harsh and great in numbers in these years of the First World War, and there was a lot of bad blood between them and the archipelago folks in general), or as punishments, for example for escape attempts; bodies were commonly just dropped into the water under the sea ice. Officially it was ordered in February to deport all imprisoned Russian troops to Russia, and the deportations were virtually complete in May.

In the first years of independent Finland, a Jaeger brigade was quartered in Vaasa barracks until 1934, then an artillery regiment moved to take their place. After the war the 1st Jaeger Battalion was stationed there until 1964, and then the men of the Vaasa Coastal Battery. Among other sites they were manning the Sommarö fort at Replot Archipelago, nowadays one of the well-known hiking sites of Replot. The battery was disbanded in 1997, and the barracks finally came into the possession of the city. These days they are partly residential buildings, partly serve as offices for a few organizations.

27.

28. Some smaller building.

29. A Swedish-language Christian school.

30.

31. War monuments to the local units.

32. There is also a monument to Lotta Svärd, a women paramilitary organization prominent in war years but abolished subsequently.

33. A peculiar feature of Vaasa center (and the nearby Vöyrinkaupunki and Hietalahti areas) are fire lanes (palokatu), which split nearly all city blocks in two in the north-south direction. Most of them are not official streets, aren't paved, and rather serve as access roads to some backyards or parking areas for rarely-used cars or boats. The fire lanes were designed as a precaution, as the modern Vaasa center was designed after a devastating fire. They are probably not that important nowadays (most of Vaasa center is not wooden anymore, for starters), but are still preserved as an integral part of the cityscape; only a few of them in the very center were built up. As far as I'm aware Vaasa is the only Finnish city that has such an extensive fire lane network.

34. Another fire lane in summer.

35. Orthodox parish administration building.

36. A car wih Åland license plates on the northern half of Kirkkopuistikko. Åland, being the only Finnish autonomous region, uses license plates with its own design and always starting with Å letter (although otherwise conforming to Finnish "ABC-123" license plate standard). Cars from Åland are usually an uncommon sight in Finnish mainland, but here in Vaasa they seem to be a little more frequent. Åland is an entirely Swedish-speaking place and Vaasa and its surroundings have many Finnish Swedes too, and it's not uncommon for people to have relatives in Åland (or in Sweden).

37. The Swedish-language theater on Kirkkopuistikko, if I remember correctly.

38. Raastuvankatu on a February evening. Street parking space in winter can be significantly lessened by snow piles remaining from snowplowing. Those are generally removed only after they get to a certain size.

39. Bacchus/Svenska Klubben restaurant on Rantakatu (Finn. Shore Street).

40. A new fancy residential building under construction on Koulukatu (Finn. School Street).

41. Basically the last thing I saw in Vaasa, the weekend before moving away from the city, was a LGBT pride event in June 2019. I had never seen a pride event before and was very curious to see one. Although in Helsinki those are yearly occasions, here in Vaasa this was the first one in over 15 years or so. It seemed quite wholesome to me.

42. The participants were marching from the central square to Hietasaari island where there apparently was some concert.

43. I've heard that in some cities these events can be disrupted by neo-Nazi and other protesters, but here everything seemed to happen quite peacefully.

44.

45. The scene at Hietasaari.

46. Governor's House (Maaherrantalo) on Koulukatu. The house was designed by Setterberg and built in 1864 as home for Gustaf August Wasastjerna, the grandson of Abraham Falander, the founder of Östermyra ironworks in the place of the modern Seinäjoki city (the modern center of the neighboring South Ostrobothnia Region), and the owner of the only private house spared in Old Vaasa by the fire. Wasastjerna still owned Östermyra works but eventully got into financial difficulties and went bankrupt in 1869. The new Koulukatu house was sold then and changed several owners, was bought in 1895 by the state, and served in 1895-1997 continuously as the residence of the governor of Vaasa County (Vaasan lääni). Notably, in 1918 the house served as the headquarters of White forces, and their commander-in-chief Mannerheim lived in it at the time. Vaasa County was abolished along others in 1997 (the country in 1997-2009 was subdivided into only six huge counties, then those were abolished as well) and the house was bought by the city of Vaasa, and is used now as the office of the Ostrobothnian Museum and for some events and ceremonies.

47. And this across the road from the Governor's House is the Ostrobothnian Museum itself (Pohjanmaan museo). This is a rather good regional museum, as far as Finnish regional museums go, although it tells mostly about Vaasa itself rather than the entirety of Coastal Ostrobothnia Region. A second major part of it is the Terranova nature museum, in the basement, telling about the nature of the Kvarken sea area. There are also art exhibitions, collections of coins and silverware, and other small things. The museum has been operating since 1896, founded by professor Karl Hedman, a doctor and an art collector.

48. Old (pre-fire) Vaasa, from the museum.

49. An interesting and rare exhibit in the museum is these banknotes from Vaasa. At the time the official Finnish goverment (the Senate) operated from Vaasa during the Finnish Civil War in 1918, they also printed their money (Finnish marks, markka) here with a distinct design.

50. The former phone company building from 1899. Some antenna tower is visible to the right, but somehow I failed to google what exactly it was/is used for.

51. In the north, Vaasa center ends at the bridge to Palosaari peninsula. Next to the bridge, on the sea shore, is the Vaasan Sähkö (Finn. Vaasa Electricity) company headquarters.

Electric lighting came to Vaasa for the first time in 1887, originally just in the church. The city officials were sufficiently impressed by it that they subsequently decided to establish an electricity company for street lighting in the Vaasa center and also for selling electricity to the consumers. The Electric Company, Elektriska Aktiebolaget, started operating in 1893, when a small power plant next to the Palosaari bridge was launched. Nowadays the same company, now named Vaasan Sähkö, is still owned by Vaasa city, although its electricity can be bought anywhere in Finland; I myself still have a contract with Vaasan Sähkö despite moving to Espoo. (The way electricity is paid for in Finland is that you have contracts with two companies, the electricity producer and the electricity distributor. The producer releases all electricity into the nationwide electric grid, so in principle it can be located anywhere and can be chosen freely; electric companies compete rather hard, and can look for new customers for example by cold calling random people and offering a discounted tariff if you switch to them. The distributor, owning the wires, is of course tied to the actual location of your home and cannot be chosen, so when I moved from Vaasa to Espoo my distributor changed from Vaasan Sähköverkko (Vaasa Electric Grid) to Caruna.)

I'm not actually sure if this old power plant is still operating; apparently it at least used to, mostly for central heating of Vaasa center (central heating came to Vaasa in 1962), but the Vaasan Sähkö office moved to this location in 2015, and a new building was built alongside the old power plant, so I wouldn't be surprised if the latter one is not in use anymore. Nowadays most electricity in Vaasa comes from the Vaskiluoto coal-fired power plant, next to the harbor; there is also a waste-to-energy incinerator at the local recycling plant (Stormossen in Korsholm), and some wind farms in the region. The power plants are actually owned by EPV Energia company (Etelä-Pohjanmaan Voima, Finn. South Ostrobothnia Power), a partially-owned subsidiary of Vaasan Sähkö.

52. A funny thing about this Vaasan Sähkö headquarters is that it is actually located at Kirkkopuistikko 0 address. It's really zero, it's the same on their invoices. I don't think I have ever seen an address with a house number zero anywhere else.

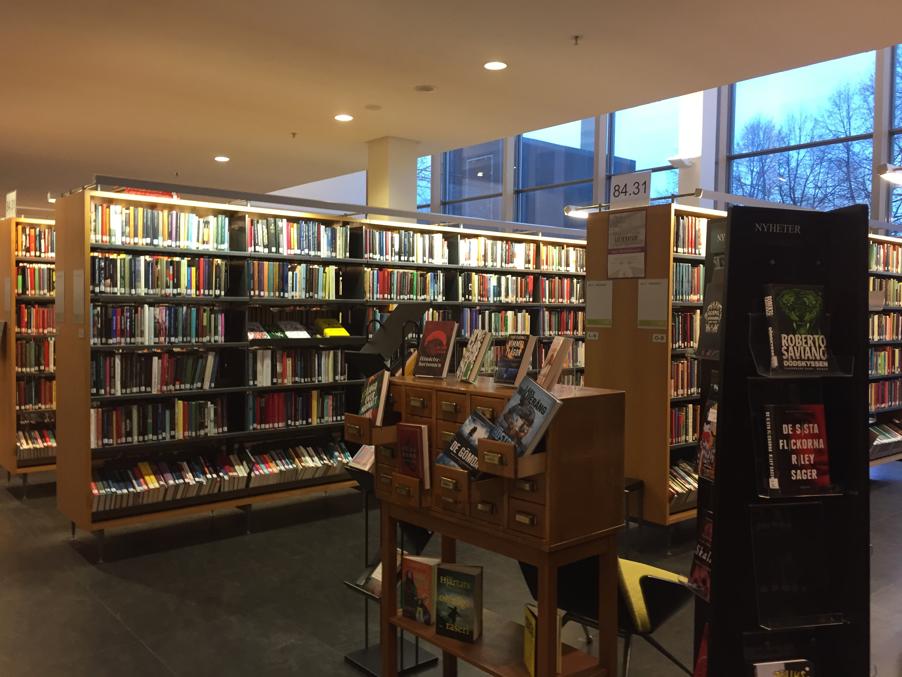

53. Vaasa city library was one of my favorite places in the city. Vaasa actually had the first public library in Finland, operating in 1794-1844. This library is its successor, founded in 1851. The building dates from 1936 and the extended glass section from 2001. There are also a few local branch libraries around the city and a library bus. A joint university library, Tritonia, also operates in Palosaari area, independent of municipal libraries.

54. This is a rather classic-looking library; although libraries in Finland generally all serve as community centers to some extent, the basic function of the library is still central here (unlike for example the new famous Helsinki central library, Oodi, which actually has surprisingly few books).

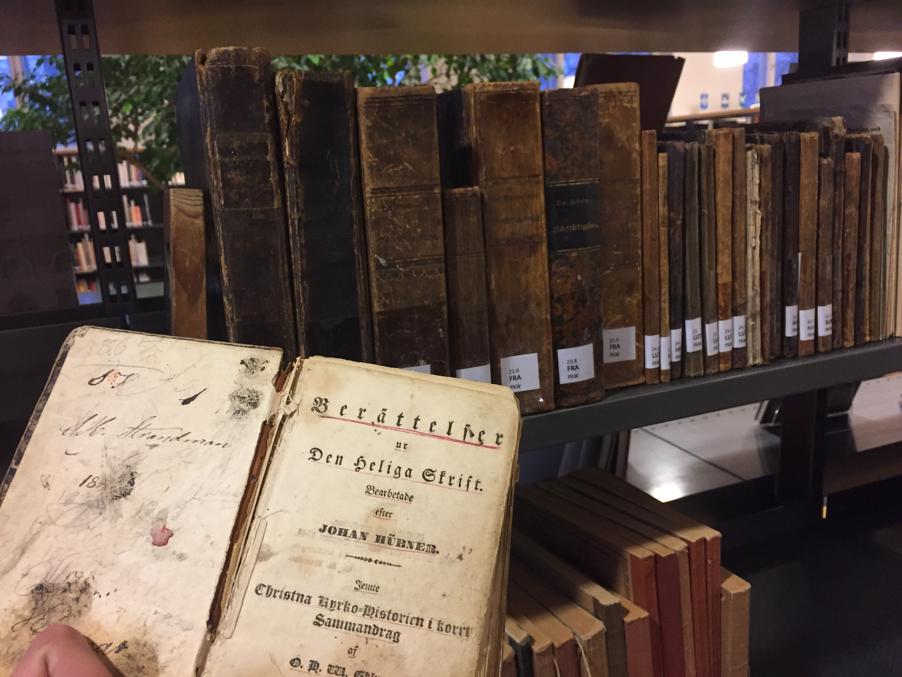

55. You can read some quite old books here! (although I don't think these can be borrowed) I also rather enjoyed a massive collection on the local history of Ostrobothnia; it seemed nearly every village had a sizable volume written about it, and there was a monography on Vaasa itself in six volumes or so.

56. A picture exhibition in the library. It would be nice to organize one of my own (I have enough good pictures for that; I had an idea to make an exhibition about the Gulf of Bothnia), but times for those should be reserved months if not over a year in advance.

57. Christmas trees being sold next to the library in winter.

58. New Scandic hotel the building of which I got to witness.

59. And let's end this part with a picture of good old December slush :) Thankfully such weather didn't happen too often.

In the next part (whenever I get around to it) we'll explore the Old Vaasa (Vanha Vaasa). Old Vaasa in truth is not large at all, so that will be a relatively short part.