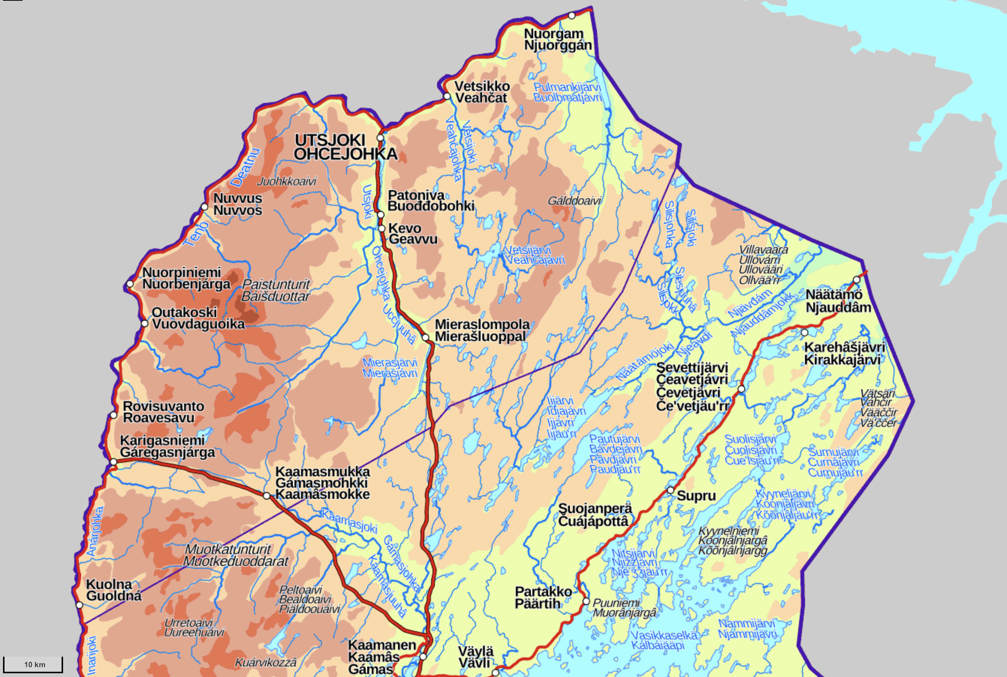

The northernmost municipality of Lapland, of all Finland and really of all EU (for, as we know, Norway is not an EU member) is Utsjoki, or in Nortern Sami language Ohcejohka. A piece of land 5372 sq. km large, but inhabited by only 1206 people, it looks like that on the map (Utsjoki is north of the violet border line, south of it is Inari):

Already on this map you can see that most of Utsjoki is sheer wilderness, pierced by only two roads coming from the south. Virtually all population clings to the valley of the great river Tana (Teno or Tenojoki in Finnish and on the map, Deatnu in Northern Sami), the border river of Finland and Norway. There are three border crossing points from Utsjoki to Norway (of six existing in all Finland), in Karigasniemi, Utsjoki central village, and Nuorgam.

1. Utsjoki is far enough in the north that it is one of the only two places in Lapland that actually begin to have a noticeably "Arctic" character to their landscapes (the other one is Käsivarsi, the northwestern panhandle of Finland). A casual traveller in Finnish Lapland might easily end up disappointed by how it doesn't actually visually look all that different from the rest of Finland (beyond the sparse population, the presence of reindeer and the spruces being somewhat narrower and sharper), if you're just driving through. Lapland is of course the most beautiful part of Finland, but you need to have at least some idea where to look at. The really beautiful places are mostly various fell massifs, but in most of Lapland they are rare and disjointed amidst endless taiga and bogs. Only when you cross into Norway the landscape usually changes almost immediately and drastically. Utsjoki (or technically Upper Lapland (Ylä-Lappi) geographical area which also encompasses part of Inari) though is somewhat "Norway-like" too and fell country covers almost all of it, except the valleys.

2. Most of Utsjoki is also nature conservation areas. Kevo Strict Nature Reserve (Kevon luonnonpuisto) is by far the largest strict nature reserve of all Finland, at 712 sq. km (the second biggest (Sompio) is only 179 sq. km). The strict nature reserve contains the Kevo canyon, the largest in Finland as well, 40 km long and 80 m deep at most, with a large waterfall (Fiellu or Fiellogorži) halfway. A hiking trail runs through Kevo between the Karigasniemi and Utsjoki roads, 63 km long. It is considered one of the most demanding official hiking trails of the country, due to its length, many steep parts (it climbs in and out of the canyon repeatedly) and nearly complete lack of shelters. Of course I would still want to try it someday (I still haven't ever done any really big hikes in Lapland or elsewhere). There is also a 87 km option (Kuivi trail) that goes away from the canyon halfway and circles back to the trailhead at the Karigasniemi side though the high fell country. It is not allowed to move in the strict nature reserve elsewhere than on these two trails, and in spring (1.4-14.6) it is not allowed to visit the canyon at all.

3. The other nature conservation areas of Utsjoki are of a much lighter wilderness area (erämaa-alue) status. Wilderness areas only exist in Lapland; ten of them were established in 1991, and two more added in 1997. These are fairly vast state-owned areas that are kept in a close to natural state, although using them for e. g. reindeer husbandry is allowed. Hiking there is of course allowed and the rules are a bit looser than in most of the country; e. g. making fire is allowed anywhere (from dry branches you can find etc.; admittedly in fell country there is not much wood available). Wilderness areas are distinct from national parks by their general lack of marked trails and hiking shelters and other facilities (although in most wilderness areas a few marked trails still may exist). They are thus the best places for someone who really wants to be alone with the nature. Most wilderness areas are in treeless fell country, fairly easy to walk and to navigate in.

Utsjoki contains Kaldoaivi and Paistunturi wilderness areas, and a part of Muotkatunturi wilderness area. Kaldoaivi (Gálddoaivi) at 2924 sq. km is the biggest single nature conservation area in Finland. It has a bit more marked trails than most wilderness areas, including the Sevettijärvi-Pulmanki trail (60-70 km), also a demanding one but with a few open wilderness huts on the way.

A less strenuous option that nonetheless does give you a good feel for these lands is the 35 km so-called Utsjoki trail, which begins and ends at Utsjoki and wanders in the fells of Paistunturi wilderness area, with a place to stay overnight at Koahpelasjärvi wilderness hut. That route I tried in the summer of 2020 and will tell about it a bit later.

4. The history of Utsjoki is not particularly remarkable. It had been a remote, difficult to reach area, inhabited only by a few hundred Sami people, for centuries. The connections to Norway were in practice much more important for the locals than the fact that this was, in principle, a part of Finland. There were many intermarriages with the Norwegian Sami, and fishing in the Arctic Ocean (which is not that far away down the Tana river) was an important livelihood. The exact Finnish/Swedish-Norwegian border in the area was only officially confirmed in 1751 by the so-called Strömstad treaty (which also removed the potential option for Arctic Ocean access for Sweden forever; not that it could be useful in any practical way at the time). The addendum to the treaty, the Lapp Codicil, nonetheless confirmed the rights of the Sami to basically ignore the new border for the purposes of reindeer husbandry and such. The border was officially surveyed over the next few decades, and a few border marks with King Adolf Frederick of Sweden's monogram can still be found hewn into stone on the banks of Tana (nowadays highlighted with paint).

5. The first church, a small wooden one, was built in Utsjoki in 1700, on the shore of Mantojärvi lake. The church became also a general meeting place for the locals. Of that church only the old sacristy from 1776 remains.

6. Since travel times to the church were very long for many locals, a "church town" emerged nearby, with modest huts for overnight stays for church visits, each hut built and used by a particular family. It is the same kind of church town that exists for example near Luleå in Sweden (Gammelstad). Nowadays 14 huts of the original 30 or so remain as an outdoors museum (Utsjoen kirkkotuvat), mostly from the 19th century, a few from the 18th. They were still in use as late as the 1930s. The old käräjätupa, village assembly house, was also among them.

7. The border was fully closed a century later, in the Russian Empire era of Finland, in 1852, causing massive changes to Sami livelihood, and causing them to eventually change to a less nomadic way of life. A bigger church was built in Utsjoki in 1853 by Ernst Lohrmann, the architect of many other Finnish churches. The church of grey stone and brick, overlooking the road and nowadays 6 km south of Utsjoki central village, looks somewhat out of place for these lands.

8. The priest's house (pappila) nearby is even older than the church, dating from 1843, and was designed by none other than Carl Ludwig Engel, best known as the architect and planner of Helsinki center. It was one of the last Engel's works; he died himself in 1840, before the house was actually built.

9. By 1885 Utsjoki got its own school. Nowadays there are three schools in Utsjoki, in all its three significant villages (central village, Nuorgan and Karigasniemi), and also a high school (lukio). In all schools it is possible to receive all education either in Finnish or in Northern Sami, and part of the high school education can be in Sami too. Finnish people started to settle down here in any numbers only in the 20th century already, and by now the Sami are a minority, but Utsjoki still retains the highest percentage of Sami-speaking population in all Finnish municipalities (45%).

10. Utsjoki was one of the last parts of Finland to receive an actual road connection; up until the World War II it was completely, as the Finnish saying goes, "beyond the roadless portage" (tiettömän taipaleen takana), reachable only by the old Finnmark trail (Ruijanpolku), passable on foot or on a reindeer sleigh in winter, existing at least since the Middle Ages. (A surviving part of this trail is a 35 km hiking route nowadays, not in Utsjoki however but much farther south, across Sompio Strict Nature Reserve in Sodankylä.) Tana river was the main and the only means of transport for the locals. The river is wide and mostly reasonably calm, but also has a few significat rapids where boats had to be portaged along the shore. The Nivajoki–Alajalve road, 4.8 km long, bypassed the biggest rapids, Alaköngäs (Finn. Lower Waterfall); it has existed in some form for centuries, and in 1928 was officially declared to be a part of the state road network, even though it was a completely isolated road section. Nowadays it is a museum road, unplowed in winter (the picture is taken in early June).

11. The first road from the south was built to Karigasniemi (Gáregasnjárga), the western village of Utsjoki. The construction started in the 1930s from the village of Kaamanen in Inari, but wasn't finished in time until the war. The remaining, relatively short section was eventually built by none other than Nazi Germans (when in the Continuation War of 1941-1944 Finland fought against the USSR, Germany was helping directly in the north), using Soviet prisoner labor. The road was finished in 1943. In Karigasniemi it crossed the border river (Inarijoki (Anárjohka), the upper course of Tana; note that it is completely unrelated to the village of Inari elsewhere in Lapland, and the river of Inari is actually called Juutuanjoki) into Norway, to Karasjok (Finn. Kaarasjoki, N.-Sami Kárášjohka) and from there to Arctic Ocean coast to Lakselv (Finn. Lemmijoki, N.-Sami Leavdnja) at the Porsanger Fjord.

The National Road 4 (Valtatie 4) was always, since the road classification system was adopted in the 1930s, the longest road of the country, from Helsinki along all of Finland to its far north; originally it ended at Liinahamari of Petsamo/Pechenga, Finland's only Arctic Ocean port. After Petsamo/Pechenga was re-annexed by the Soviet Union in 1944, the National Road 4 was re-signposted via Inari and Kaamanen to Karigasniemi. It therefore was widely considered to be a some sort of "edge of the world" place. The road was paved at some point but otherwise never really improved much, and is quite narrow and hilly for a road leading to an international border crossing. The traffic is however light enough it's not a problem in practice.

12. The border bridge at Karigasniemi, from the Norwegian side.

13. The road to Utsjoki central village was built in 1959, and unlike the Karigasniemi one it did see some straightening and widening over the years. After Kaamanen it climbs into the uplands, not to the treeline but to the fell birch zone at least, and thus has some landscapes quite unusual for Finland. Unfortunately I never took any pictures from there. From the uplands the road slowly descends into the valley of the Utsjoki river. In its lower reaches, just before the central village, it forms a wider lake called Mantojärvi (Máttajávri), and at the village itself flows into Tana.

The name Utsjoki comes from Northern Sami Ohcejohka, but the origin of that name is unknown. It is possible that the Northern Sami name is a corrupted form ot its Inari Sami name, Uccjuuvâš, meaning simply "Little River". Inari Sami live, as the name suggests, only around Inarijärvi lake, and were and are a quite small group, but who knows how people moved ages ago and how place names spread.

14. The road to Utsjoki used to end there, but in 1993 it was continued with the Sami Bridge (Saamen silta) over Tana. This is the second border crossing to Norway in Utsjoki.

15. With the completion of the bridge, National Road 4 was rerouted once again from Karigasniemi to the central village. On the Norwegian side European Road E6 follows the north bank of Tana in a thinly populated area.

16. An abandoned short road stretch near the bridge. I like abandoned roads; in Finland small abandoned road segments are not always reclaimed and can sometimes be found in places the road was improved.

17. Utsjoki central village is not a very remarkable place otherwise, being home only to about 320 people. This is the municipal council building.

18. The economy of the few existing villages at various Finnish-Norwegian border crossings is heavily based on border trade; Norway is one of the most expensive countries in the world, significantly more expensive than Finland, and although the salaries are higher too, Norwegians are normal people like we all and can and do shop at cheaper Finnish stores when practical. In truth there aren't all that many Norwegians living close to the Finnish border, so it's not really a very practical option for most. And you cannot bring too much alcohol and some other goods across the border anyway; since Norway is not an EU member, customs limits are much stricter than between e. g. Finland and Estonia, and Norwegian customs officers may occasionally carry out spot checks at the border.

In case of Utsjoki central village border trade however is not as important here as in Karigasniemi, Nuorgam, Näätämö or Kilpisjärvi, as there aren't really any villages close by on the Norwegian side. Thus there's just one modest non-chain store.

The economy of Utsjoki municipality is otherwise based on reindeer husbandry and tourism. Utsjoki is actually the municipality with the biggest gender income disparity in the country... in favor of women! As of 2017, Utsjoki women were earning about 2.18 times (times, not percent!) more than the men. This is the biggest such gap in Finland; on the opposite end is Perho in Central Ostrobothnia, where men earn on average 1.72 times as much as women.

The reason for this phenomenon is that more men are employed in reindeer husbandry, which is a seasonal and not especially well-paying job, involving much physical labor, while more women are employed in education, healthcare and white-collar jobs, not necessarily all that lucrative by themselves too (of these only the doctors are compensated really well, but not e. g. nurses), but still comparing very favorably with reindeer husbandry, which is really more of a calling than a job these days. Women earn more than men in some other municipalities mostly in North Finland, but on average the gender pay gap in Finland favors men, same as everywhere.

19. Every proper municipal center must have a grillikioski...

20. ...And a bar. This one is named Rastigaisa, which is a prominent mountain 1067 m high in Finnmark in Norway, a few tens of kilometers from Utsjoki. More properly the mountain is named Rásttigáisá. In Finland this is probably the best known mountain of Finnmark, if only for the reason that it was mentioned in Sampo Lappalainen (Sampo the Lapp), one of the most popular tales of Zacharias Topelius (1818-1898), a Finnish-Swedish writer best known for his children tales. Rásttigáisá these days can be reached by a 16 km marked trail; 16+16 is 32 though and you probably will want to do some camping on the way.

21. The road Karigasniemi-Utsjoki-Nuorgam (148 km), along the south bank of Tana, is named Regional Road 970. Utsjoki-Nuorgam part was built in 1971; Karigasniemi-Utsjoki originally in 1972 as a "trail-road" (polkutie, a status extremely rare nowadays), and as a regular road in 1983. The road is rightly known as one of the most beautiful, if not the most beautiful in Finland; it probably cannot compare to for example roads along Norwegian fjords, but the Tana valley, bounded by endless fells on both sides, is very beautiful in its own right; and Finland unfortunately cannot boast many scenic roads, which I believe is a major reason why Finnish nature is often underappreciated in first place.

Tana is known first and foremost as a great salmon river; it's one of the very few major rivers in the north that are free flowing and never were blocked with any hydroelectric dams. Many tourist businesses in Utsjoki cater specifically for salmon fishing. About 50-100 tons of salmon are caught in Tana yearly, usually split about evenly between Finnish and Norwegian fishermen. This is all either by tourists or by locals for their own needs; there haven't been any full-time fishermen in Tana valley for decades, and even as an irregular side income it is practiced by only a few people nowadays.

22. Spring in Tana valley, and by spring I mean, yes, early June. It is a pretty northern place, after all (although in summer it can get quite hot, and the ruthless mosquitoes are by right nicknamed the Lapland Air Force). Both polar night and midnight sun last for about two months in Utsjoki, and their coming and leaving at Nuorgam, the northernmost point, are often both announced by the Finnish media. I've seen midnight sun many times but never an actual polar night; I really should try someday just for the experience.

23. And this is Nuorgam (Njuorggán), 70° 05' N.

24. Nuorgam has several "northernmost in the EU" things, like, for example, a bar, named "Stallu's Lair" (Staalon pesä). A Stallu is, in Sami mythology (or what we know of it, for not much of that mythology has been preserved), a man-eating giant, evil but usually somewhat stupid. The bar in truth shut down and the building was being renovated for some other purpose.

25. The northernmost supermarket and Alko store are still doing well, though (or were before corona...). The third and the last border crossing in Utsjoki is located in Nuorgam, and it's not a very long drive from it to large villages of Tana Bru and Varangerbotn, and a somewhat bigger one to the town of Vadsø. Note the opening times being announced both in Finnish and Norwegian time zones.

26. The memorial stone for the northernmost point of Finland and the EU at nearly the very border with Norway. Technically the northernmost point is some 400 m farther to the north (in the middle of Tana), and the northernmost point on the land is, accordingly, on the bank of Tana, but that's someone's private land.

27. On September 4, 2020, when this picture was taken, the temporary border control between Finland and Norway was in force, as part of coronavirus restrictions. Leaving Finland was allowed (and Norway itself did not implement any kind of control on their side), but entering was allowed only for citizens and residents of Finland, on work trips and for members of relatively vaguely defined "border communities"; also a two-week self-quarantine was recommended for people returning from Norway. Border trade suffered a lot as a result of these restrictions, although the main pain point was not the Norwegian border but the twin city of Tornio and Haparanda at the Finnish-Swedish border (same restrictions existed for Sweden). The restrictions and border control were eventually cancelled, but reinstated again only a week later as the corona cases growth in both Norway and Sweden began to accelerate, and remain in force as of the time of this writing. By now I have a very negative view of most corona restrictions myself, but it's not a good time or place to go into this subject here.

As for me, I actually travelled into Norway for a few days on my vacation, and took this picture when returning back. As a resident of Finland who had my passport and residence permit with me I didn't have problems re-entering the country, and was just asked where I live and where I was coming from. This is how the actual border control looked like; the traffic lights are red coming from the Norwegian side. (The border guard, seeing that after entering Finland I turned around and stopped here, looked out of his container, but, seeing that I was just taking pictures, waved in a friendly way and went back.)

28. But let's now in the end talk about a less depressing subject, namely, the Utsjoki hiking route! There aren't really all that many hiking trails in Utsjoki, because, as I said, the fell areas have a wilderness area status, and wilderness areas have few official trails. Nonetheless one such trail begins and ends in the center of the Utsjoki central village.

The trail, circular, 35 km long and with a wilderness hut (and a good place for tents) about halfway, is very well suited for a two-day hike, which in itself is not a very common coincidence. It doesn't have any major individual natural sights, but nonetheless showcases the nature of Utsjoki and Paistunturi wilderness quite well, with a continuous bare fell landscape, streams, small mires and lakes and several large ravines.

Apart from some information signs at the trailhead used to be an information "nature hut", but it burned down in 2017 and so far at least hasn't been rebuilt. The trail is marked with small sticks in the ground with orange-painted tops, and also with signs at a few crossroads; getting lost would be pretty hard, but of course you still really should have GPS and preferably a backup paper map. Myself I picked this trail because I was staying for almost a week in a motel at Kaamanen (Neljän Tuulen Tupa, "The Hut of Four Winds"), some 80 km south or so of Utsjoki, and was itching to do a longer hike somewhere nearby (that was before the short Norway excursion). The motel is a very cozy place with log walls, tasty and cheap food and nice hosts, a rare case when I can explicitly recommend some accommodation place.

29. The trail starts, as you might expect, with a fairly steep but not too long climb from 80 to 220 m above sea level through a fell birch forest. Utsjoki, or at least its northern parts, lie beyond the pine forests border; only birch forests can survive there. Somewhat counterintuitively coniferous trees are actually less tolerant to cold than the birch, which in the north turns into the low twisted fell form, and farther north (or farther up) into dwarf birch which barely rises above ground. Pine is also more tolerant to cold than spruce; spruce forests border passes much farther south, through the northern parts of Sodankylä.

30. Soon we begin to walk along a reindeer fence and then reach a gate in it. Such gates might be more convenient to use in some places but here it's very basic, you're supposed to move a few poles aside to walk through, and then put them back into place.

31. And here we are beyond the treeline. Paistunturi wilderness proper begins a kilometer or two from this place, it's not marked in the terrain in any way. But this is how most of it looks; just very shallow continuous bare fell uplands.

32.

33. And from here you can actually see the aforementioned Rásttigáisá! Being some 700-800 m higher than this area, it's easily seen from tens of kilometers away. And it sports snow patches in late August, which means the snow never melts on it completely. Finland, as far as is known, only has one never melting snow patch, on the slope of Ridnitšohkka, the second highest mountain in the country (1317 m), a neighbor of the highest one, Halti. Halti is located on the Norwegian border and its true summit is actually in Norway, so Ridnitšohkka is the highest mountain which actually has its summit in Finland. Such (relatively) high mountains are only found in Käsivarsi in the extreme northwest of Finland. Utsjoki and Paistunturi's highest fell, Guivi, is only 641 m high.

34. The Tana valley can be seen behind in its majesty, though we never get a completely open view.

35.

36. Some cloudberries could still be found, while in South Finland their short season ends by the end of July or so.

37. Otherwise the tundra-like carpet is made up of crowberry and dwarf cornel, both edible but mostly tasteless.

38.

39. The highest point along the trail is the fell named Roavvoaivi, at about 445 m above sea level. The trail itself passes by its slope, but it's easy to climb 50 m more to the felltop, as the slope is so shallow and the fell terrain is easy to walk off trail too.

40. Roavvoaivi summit.

41. More Norwegian mountains with snow patches can be visible from Roavvoaivi in the north. The map says there is a palsa mire closer by; it is a specific type of mire common in Lapland fell areas, with round, not very large but fairly prominent small hills, which are caused by isolated permafrost lenses lifting up the terrain above. Finland does not have any continuous permafrost areas, but isolated permafrost "islands" do occur. Nonetheless personally I could not see anything out of usual from here.

42. The day started sunnier but rain clouds started to gather towards the evening. The last sunlight of the day.

43. And now we're descending to a ravine with a long narrow lake at the bottom. This is Koahpelasjärvi, on the shore of which the place to stay the night is, but there's still some distance to walk. Koahpelasjärvi drains to the north, through a river in a narrow gorge, into Tana.

44. After some 2-3 kilometers and the final descent towards the lake I think we can see something.

45. Koahpelasjärvi hut is a typical autiotupa, an open wilderness hut. It has very basic facilities (place to sleep, officially for 8 people, a table, a fireplace, a gas stove and some cookware) and it is allowed for everyone to stay in it anytime without any payment or reservation. You are not supposed to stay in such hut for over two nights in a row and if it gets overcrowded, the first to arrive is the first who has to leave to make place for newcomers (thus, unless you know what you are doing, it is very unadvisable to hike without a tent relying only on these huts). Of course it's on you to follow this etiquette, it's not like someone is overseeing you. Firewood is available from a shed nearby, there's a dry toilet, and there is a stream nearby and a lake so there's water too. Your trash you're supposed to take away, unless it's compostable or cleanly burnable. Such huts were sometimes originally built for the purposes of for example hunting, fishing or reindeer husbandry, which is where the tradition of such huts comes from, but now they're mostly meant for tourists.

46. Since the place is an open wilderness hut, a sleeping place there is not guaranteed (there exist also huts where you can reserve a bed for a small payment, or sometimes the whole hut), so it's more common for people to pitch a tent nearby and use the hut only for drying their stuff, cooking or socializing. I found the hut empty (I met only a handful of people on the whole hike, and none really far from civilization) but still pitched my own tent, assuming someone would yet come. I don't really like sleeping in a tent (I've got a bit better at this this year thankfully) but sleeping in a room with unfamiliar people with no private space is even worse.

47. It was close to sunset already and mosquitoes appeared out of nowhere; I assumed in late August they would be dead already and didn't even take mosquito spray with me, but apparently they weren't. Soon however a rain started, which drove mosquitoes away and was marginally better. I had a modest dinner and went to sleep in a tent, but eventually, after dark already, decided to move into the hut, since no one came in the end. Sleeping in a hut was nicer although of course I still had to sleep in my own sleeping bag, there aren't any bedsheets or even a mattress.

48. The hike continued next morning. It was still lightly raining. From the hut the trail passed through another ravine valley.

49. A shelter by a small lake. Also empty. The sign says it's a laavu, but it's actually not a laavu but a kota. A laavu is an open lean-to and a kota is an enclosed conical hut with a fireplace in the middle, resembling a traditional Sami hut in shape. Kota is awkward to sleep in, although it's not forbidden.

50.

51. We're starting to descend along a moderately strong stream.

52. And eventually you have to cross it by fording! Okay, you don't really have to; the trail also continues along this bank and there wouldn't even be much of a detour. So I suppose this ford is just here for the fun experience. It actually doesn't seem to be in a place that would be all that easy to ford; you're going at least knee-deep, which is already very unsafe especially if you don't have anything to hold on. Myself, I had my hiking sticks and of course there are these loops you can hold on, so I bravely walked in; my boots were rather wet by this point anyway. 9/10 would recommend.

53. The annoying feature of this trail is that it comes down here back to the road, near the church which as we remember is some 6 km south of Utsjoki proper; and then it climbs back again to go to Utsjoki via some more fells. So you're tempted to just walk along the road the rest of the way, or maybe call a taxi or something, or at the very least leave you backpack here and walk on without it, stopping by to pick it when you drive back. I however decided to do this the proper way and continued the hike as it was supposed to go without any cheating.

54. But here by the church we can check out those church huts while we're here. Well, about these I have already told before.

55. And so we climb up again, following a quad bike track for a short while. These tend to make terrain really muddy and messy, but quad bikes make reindeer herder job much easier, so there's that.

56. A lone reindeer. Reindeer are extremely common in Lapland, given that they are purposefully bred and herded here. Virtually any long drive in Lapland is bound to encounter some reindeer. For some reason they tend to completely ignore cars, even if you honk or yell at them, and if they block the road you cannot really do anything until they walk away. But if you're a hiker, it's all different; they avoid humans, or unfamiliar humans at least, and it's difficult to take a picture of a reindeer in the nature up close (still nowhere as difficult as taking a picture of an actual wild animal, of course).

57. Well, now this one's running away too. I love reindeer, anyway. Glorious beasts.

58. And the final descent — towards the Tana valley and Utsjoki central village. The car awaits, and then 80 km away a warm shower and a good dinner...

Practical part: by car it's 1270 km from Helsinki to Utsjoki and 1410 km from St. Petersburg to Utsjoki, necessitating at least a two day drive (unless you have a second driver of course).

The nearest train station to Utsjoki is in Rovaniemi (450 km away) and the nearest airport is in Ivalo (175 km away). There are bus connections from both Rovaniemi and Ivalo, to all of Karigasniemi, Utsjoki central village and Nuorgam, 1-2 times a day. See bus search. Since there aren't many roads in the area, it is possible to also get to various hiking destinations (such as the Kevo trail) by these buses. It should also be possible to rent a car both in Rovaniemi and at the Ivalo airport.

There are accommodation options in all of Karigasniemi, Utsjoki central village and Nuorgam; check out Booking.com as usual. You will have much more options with a car, of course, for example you could stay in Neljän Tuulen Tupa in Kaamanen 80 km to the south like I did. 80 km by car here in the north is really nothing.

All of Karigasniemi, Utsjoki central village and Nuorgam have grocery stores, the one in Utsjoki central village is in truth the smallest one (as I mentioned, that's because border trade there is not as prominent). All of these places also have at least one place to eat. I haven't tested any accommodation or food options in Utsjoki myself so I cannot really tell more.

Links to official hiking destinations descriptions:

- Kevo Strict Nature Reserve

- Paistunturi Wilderness Area (including the trail described)

- Kaldoaivi Wilderness Area (including Sevettijärvi-Pulmanki trail)