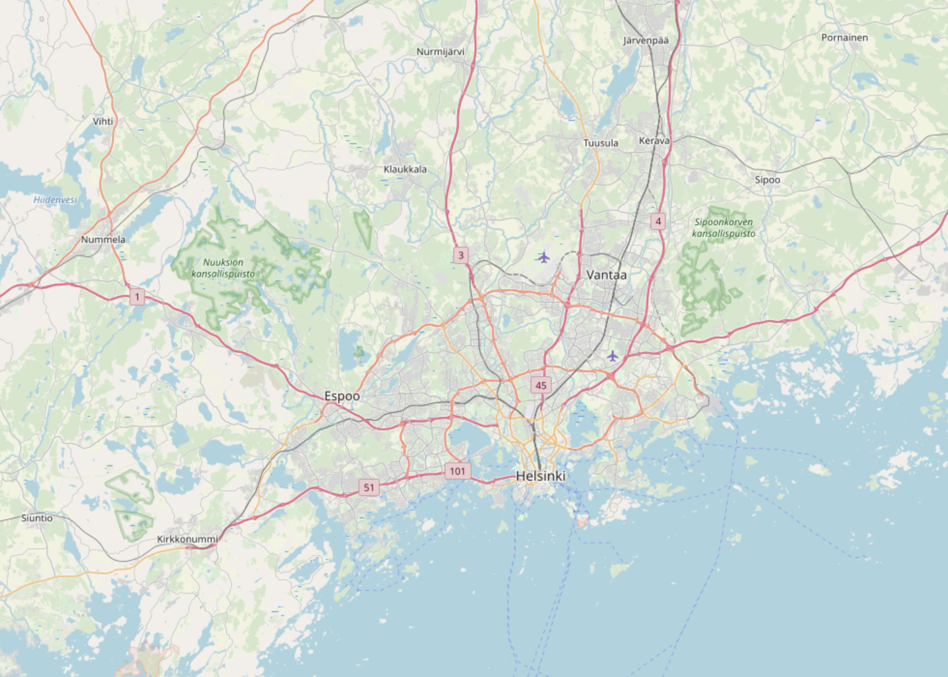

Helsinki is the capital of Finland, and by far its biggest urban area. Although the population of Helsinki proper is about 650,000, it forms a contiguous urban area with several different municipalities, over 1.2 million people large (~1/5 of the population of the country). With the belt of outer commuter towns, it exceedes 1.4 million people (~1/4 of the population). In comparison, the second biggest urban area (Tampere) is home only to 335,000 people.

As such, Helsinki is currently the only city in Finland having highly developed and well-functioning public transport. As of 2019, it is the only Finnish city having any form of commuter rail, metro, trams and BRT (bus rapid transit). In other words, all other Finnish cities are limited to basic bus networks. Car traffic dominates other Finnish cities, while in Helsinki car ownership and especially car use is drastically less widespread (though still common). While other cities are undertaking some steps to improve their public transit (Tampere in particular is building a tram line, and regional train service from 2020 will be improved around Tampere and in a few other locations), they are still completely incomparable to Helsinki.

Since summer 2019, I've been living in Espoo (Helsinki suburb) and as such, have an ample opportunity to experience Helsinki public transport on my own. Previously I also lived in Vaasa (a much smaller Finnish city), Yekaterinburg (a Russian city roughly comparable to Helsinki in size), and in St. Petersburg (a Russian city much bigger than Helsinki), which all form useful reference points. In this two-part article, I'll try to explain Helsinki public transport as best as possible.

Let's start with a short summary:

- Helsinki should in most regards be considered only as a single entity with its nearest suburbs, Espoo and Vantaa; all three of them form a contiguous urban area ("capital region") with 1.2 million population

- All public transport in the capital region and nearest cities is managed by a single authority, HSL (Helsingin seudun liikenne, Helsinki region transport). This allows to have unified tariffs, coordinated timetables, transfer hubs etc.

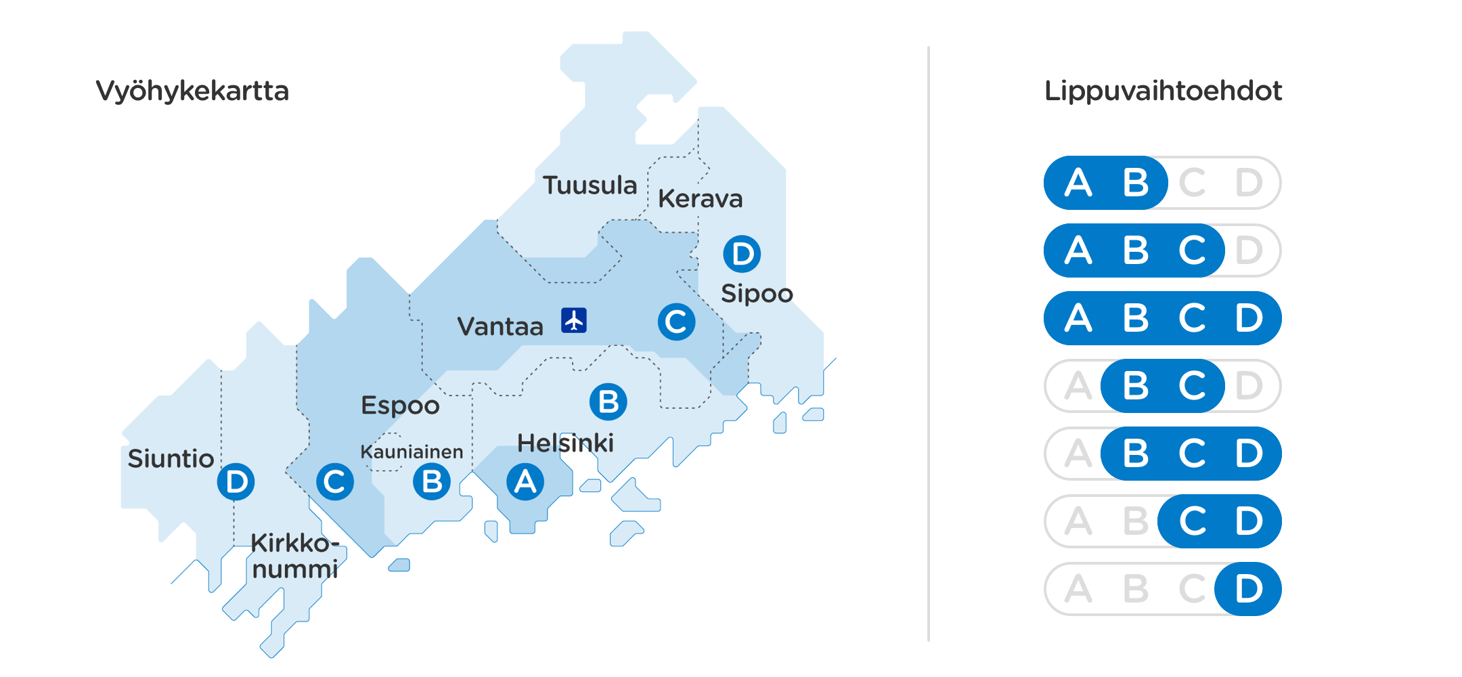

- HSL-serviced territory is split into four tariff zones, from A to D. Tickets can be valid for one or several zones, but normally at least two (available options are AB, BC, CD, D, ABC, BCD and ABCD)

- With the exception of buses, tickets for all kinds of transport are not sold aboard and must be bought beforehand. There are paper tickets sold at ticket machines; tickets loaded on HSL cards; and tickets bought through an app. There is no difference in price between these options

- There are single tickets (allowing unlimited transfers within at least 80 min), day tickets (unlimited pass for 1-7 days) and season tickets (unlimited pass for 30+ days). All these tickets are valid on all kinds of transport. Single ticket for AB or BC zone costs 2.80€, for ABC 4.60€. 30 days season ticket is 59.70€ for AB or BC, 107.50€ for ABC. Buying a season ticket at this cost require being resident at one of the HSL area municipalities. Season ticket allows buying a single ticket outside its zones with a discount

- Children under 7, people with baby prams, blind people, military invalids and war veterans travel for free. Children 7-17, pensioners and disabled people get a 50% discount. Students get a 45% discount only for season tickets

- There are no conductors or barriers in any transport. Only on buses drivers check tickets at the entrance. In general there are only fairly rare random checks by ticket inspectors, which can issue a 80€ fee to people without a valid ticket

- All HSL public transport operation and maintenance costs about 750 million € per year. Half of this amount comes from ticket sales, and the second half from municipal budgets, proportional to actual transport use in them

- The main transport in Helsinki center is its tram network, and to a lesser extent also buses and a part of the metro line. There are aggressive measures to reduce car use (tolled street parking everywhere, off-street parking also at steep fees, dedicated bus lanes and tram tracks, low speed limits, bike tracks). They are effective, and statistics show that, despite rapid population growth of the capital region, amount of car trips to Helsinki center is continuously dropping

- Outside of the inner city there is a trunk route network, including two and a half commuter train lines, one metro line and a few special trunk bus routes. They have low intervals (within capital region on weekdays mostly 2.5-10 min), and in practice form the principal axes of city growth and multi-storeyed construction. Trunk transport stations can be reached on buses, and some of these stations have large bus transfer terminals. There are also cheap or free park-and-ride facilities available

- Car use outside of the inner city is not really limited, and good roads make car trips fairly convenient (two half-ring and six radial roads, with motorway or near-motorway quality, 80-100 km/h limits and no in-grade intersections or pedestrian crossings); however street parking is still mostly time-limited, although free

- All HSL transport is partially or completely low-floor. All train and metro stations having stairs or escalators are also equipped with elevators

- Apart from using the bike track network, bikes can also be carried on commuter and metro trains for free. A few years ago also city bike rental has been launched at very attractive tariffs. Still bikes do not constitute a particularly large share of transport (a few percent of all trips)

- For navigation there is an app, a route-finding website, and ample information at stops and stations. For real-time tracking there is information in the app and displays at stations and even some bus stops

- Most routes operate between about 05-06 in the morning and 00-01 at night. Late at night when no other routes are operating there are night buses

- With very rare exceptions public transport vehicles, stations and stops are clean and safe

- Public transport is being actively developed; the biggest finished projects of the 2010s are the new commuter train ring line through the airport, and the extension of Helsinki metro to the west in Espoo. Metro construction is still ongoing, and light rail construction has started. Major plans for the near future are the extension of Helsinki tram network to the east using massive tram bridges over the sea, and the construction of the 3rd and 4th tracks for commuter trains in Espoo

Please note that this description is up to date as of December 2019, and I do not guarantee that I will continue updating it, as the Helsinki public transport continues expanding and developing. This is a purely educational effort made as a hobby (as no comparable descriptions in English or Russian are currently available anywhere online), and you should always refer to official websites and other sources for up-to-date information.

Please also note that in several places in these articles I show maps from other sources, mostly from HSL (Helsinki public transport authority). It would have been quite difficult to avoid that, and I would have needed to basically redraw these maps myself. All maps are reproduced in their original form and have sources attributed. Since this is a non-commercial work (not even ad-supported), I hope HSL and other entities quoted take no issue with that. All pictures however are my own work.

A bit of geography and history

Helsinki is located on the south coast of Finland, on quite low but rocky terrain, originally covered with mostly coniferous forests, with many low but steep rocky hills still visible in the cityscape. The coastline is quite irregularly-shaped, broken with small and big bays, with skerry guards and bigger islands off the coast. Founded in 1550, Helsinki became the capital of Finland in 1812, and really started growing only in the second half of the 19th century. Its location is quite advantageous, with good sea harbors, international connections, and milder climate than most of the rest of the country enjoys. Finnish road and railroad networks have developed around Helsinki, although since the country is quite large (over 1200 km long) and Helsinki is right on its southern edge, Helsinki is not as prominent transit bottleneck as many country capitals are.

What exactly constitutes "Helsinki" may mean different things in some contexts, and it is important to define them particularly in regard to public transport.

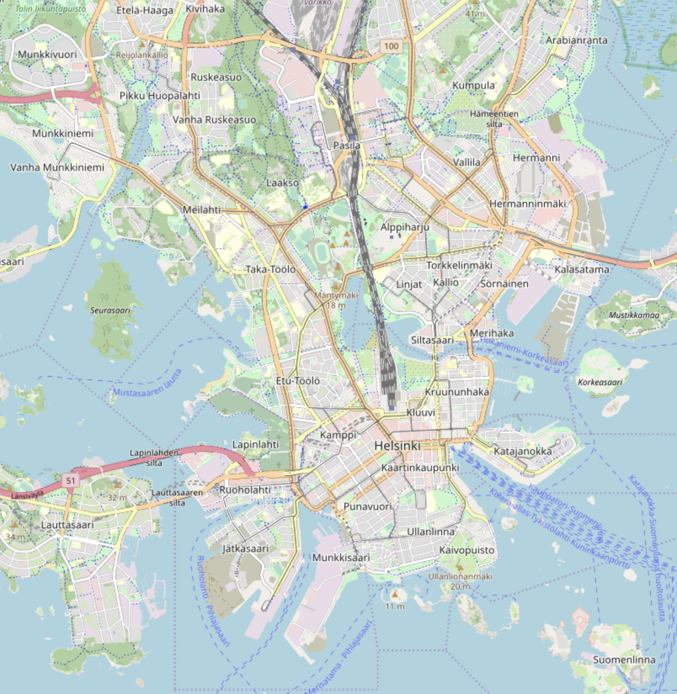

- Inner city (kantakaupunki), population about 200,000, is Helsinki core and surrounding areas on the Helsinki peninsula, roughly circular and 5-7 km across. Downtown, if you will. Most tourists in Helsinki only ever see the inner city; this is where most of the sights, and also all passenger harbors are. So are most jobs, predominantly office ones. Inner city own population is also quite sizable, although these days it is expensive to live there. Inner city is where the public transport coverage is the best, and car use is conversely severely (and intentionally) hampered. There is no exact definition of where the inner city ends, but it is widely considered to roughly correspond with the tram network coverage. Ticket zone A.

- Helsinki proper, population about 650,000, is the municipality of Helsinki. It spreads to the north and especially to the east of the inner city, reaching in particular forested unbuilt areas in the east. Although most of Helsinki is still built up fairly densely by Finnish standards, most of it is much less dense than the inner city, and includes nature areas, industry and even some agriculture. Ticket zones A and B.

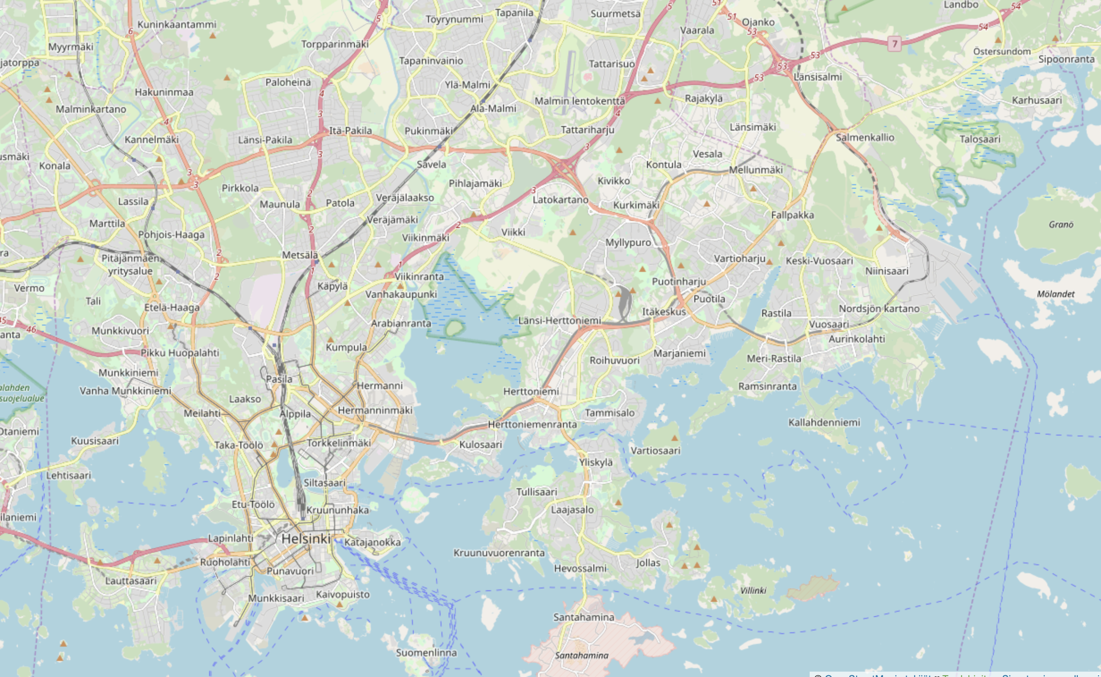

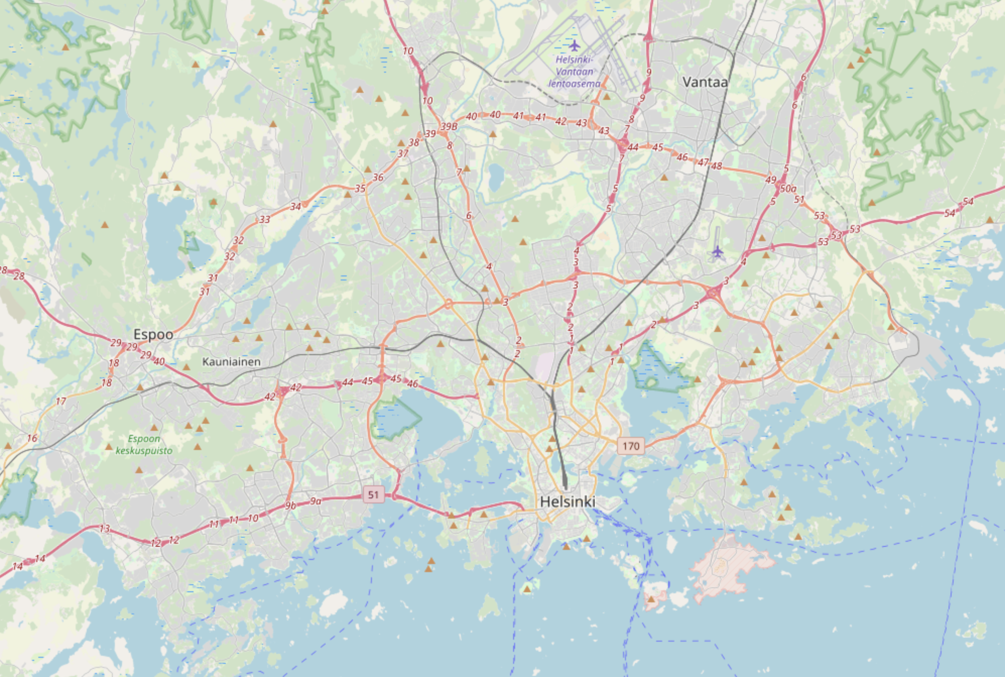

- Capital region (pääkaupunkiseutu, pk-seutu), population about 1.2 million, is Helsinki along with three other municipalities: Espoo, Vantaa and Kauniainen. All of them are legally independent cities, but mostly just blend into Helsinki and each other with no natural border. Espoo is west of Helsinki, Vantaa is in the north, and Kauniainen is a peculiar small enclave of Espoo. Capital region is what is most often meant by "Helsinki area", and it has a single unified public transport system. Geographically, it is a roughly semi-circular area, centered on the inner city and 15-20 km in radius. Ring III (Kehä III), the outer ring road of Helsinki (technically semi-circular), is often colloquially referred to as the border of the capital region, which is roughly true for western and eastern direction, but in the north most of Vantaa actually lies beyond the Ring III. Ticket zones B and C.

- Greater Helsinki (Helsingin seutu, Helsinki region) is capital region plus commuter towns. According to the common definition, it is over 1.4 million in population, and its biggest city outside the capital region would be Hyvinkää (46,500). However its boundaries are fairly imprecise, and some people commute to Helsinki from as far as Tampere, Kouvola and Jyväskylä (240 km away!). Greater Helsinki towns closer to the capital region (like Kirkkonummi and Kerava) are part of the Helsinki public transport system, but more distant ones aren't. Those are accessible by regional transport, which in practice means regional trains along the railroad Main Line, and limited bus service everywhere else. Within HSL area ticket zone D.

Public transport has existed in Helsinki since 1888, originally as horse-drawn carriages, although the railroad was originally built in 1862 and can probably be also thought of as a form of public transport. First trams appeared in 1900, and first buses in 1921. In 1969 came electric commuter trains, and in 1982 metro. Currently the public tranport modes in Helsinki are commuter trains, metro, trams, buses and a ferry. Some bus routes are designated as "trunk lines", forming a primitive BRT (bus rapid transit) system, and a light rail line distinct from regular trams is currently under construction. The only discontinued public tranport mode is trolleybuses, used in Helsinki in 1949-1974 and again 1979-1985.

Overview

All modes of public transport form a single highly integrated system, coordinated under a single authority, named HSL (Helsingin seudun liikenne, Helsinki region transport). HSL is a company jointly owned by municipalities where it is active. It is responsible for overall planning and coordination of the public transport, ticket sales and control, and information services. All actual transport services are bought by HSL from other providers, which currently are:

- Commuter trains: Pääkaupunkiseutu Junakalusto Oy (Capital Region Train Stock Company, joint municipal company, owns and maintains trains) + VR (State Railways, state-owned company, operates trains)

- Trams and metro: HKL (Helsinkin kaupungin liikennelaitos, Helsinki City Transport Facility; a municipal company)

- Buses: a number of mostly private bus companies, including Helsingin Bussiliikenne, Nobina, Pohjolan Liikenne, Transdev and some small ones

- Ferries: Suomenlinnan Liikenne Oy (Suomenlinna Transport Company; a company owned by the city of Helsinki)

Tight integration under HSL umbrella provides many benefits, including a unified ticket and zone model, synchronized timetables, transfer hubs and others.

Tickets and prices

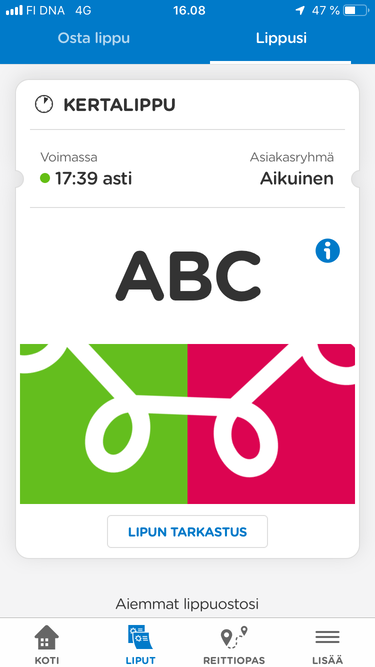

Tickets can be bought as paper tickets, loaded on a HSL card, or through a phone app. Paper tickets buying and HSL card loading is generally done through a ticket machine, or possibly in another place like a HSL service point or R-Kioski chain store. As of 2019, only non-"trunk line" (non-BRT) bus drivers still sell tickets on boards for cash, at a higher price than normal. With all other kinds of transport tickets have to be bought before boarding. Tickets can be valid for a single trip, for one or several days, or for a season (30+ days). Season tickets require a HSL card or an app, they are not sold as paper tickets.

A HSL card can be bought at their service point (there are only a few in Helsinki center) or online. The card itself costs 5€. Cards are generally personified. Loading cards (season tickets, or balance for buying single tickets) can be done in ticket machines; oddly enough there is still no opportunity to do this online, although this has been promised for some time. When using the HSL app, tickets can be paid for from the phone balance or directly from a bank card, if you specify your bank card data in it. Tickets and balance cannot be transferred between the card and the app. Tariffs are completely equivalent, and the choice between the card and the app is a matter of personal preference; I for example trust the card more, but many people don't enjoy carrying an extra card on them.

Ticket costs vary by zone. The new zone system is quite recent, having been introduced in spring 2019. The previous system was strictly based on municipal boundaries, which did not make much sense anymore (eastern Espoo is much closer to Helsinki center than eastern Helsinki is, but it cost more to travel there). The new system is mostly based just on distances from the center: A is the inner city, B and C is the rest of the capital region, and D is for outer towns of Greater Helsinki.

It is possible to buy tickets for zones AB, BC, CD, D, ABC, BCD or ABCD (so, single-zone tickets are available only for D). The prices are as follows:

| Single | 1 day | 7 days | 30 days (season ticket) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB, BC, D | 2.80€ | 8.00€ | 32.00€ | 59.70€ |

| CD | 4.20€ | 11.00€ | 44.00€ | 87.00€ |

| ABC | 4.60€ | 12.00€ | 48.00€ | 107.50€ |

| BCD | 5.40€ | 14.00€ | 56.00€ | 115.80€ |

| ABCD | 6.40€ | 17.00€ | 68.00€ | 156.40€ |

Of course the actual pricing is more flexible. Day tickets can be bought for 1-7 days, and season tickets for any number of days beyond 30 days; longer tickets get a slight discount. Children until 7, blind people, military invalids and war veterans travel for free. People accompanying a baby pram also can travel for free. Children 7-17, students, pensioners and handicapped people get discounts (45% for students and only for season tickets, 50% for everybody else).

Single tickets are more properly valid for a short period of time (80-110 minutes, depending on the zone). It is possible to change between all kinds of public transport freely within that time, and if the ticket expires it is allowed to continue the current trip (but with no more transfers obviously). Currently the only special ticket specific to one kind of transport is a return Suomenlinna ferry ticket, which allows to travel to Suomenlinna and back again with 12h time limit for 5.00€. There used to be tram-only tickets which were abandoned with the zone reform.

Season ticket prices are given for HSL municipalities residents. People outside of HSL areas can also buy them, but at a quite steep (2.5x) price. When travelling with a season ticket beyond its area, it is possible to buy an "extension" single ticket with a discount, with a HSL card or app.

Tickets are only checked by bus drivers, in regular non-"trunk line" buses, where passengers enter through the front door and are supposed to buy or show their ticket or validate their card at that point. In other kinds of transport there are only unattended ticket validators (in passenger compartments in commuter trains, trams and trunk line buses; at station/landing entrances for metro and the ferry). These are only necessary to use when buying a single or extension ticket with an HSL card. With a season ticket on hand, whether on a HSL card or in an app, you can ignore them and just use the transport, which is hugely convenient.

Ticket inspectors make random checks in all kinds of transport (including regular buses; even though the driver checks tickets there, it is possible e. g. to enter through middle/back doors, which are meant for exiting people and for prams). Checks are quite rare; it is possible to go a month or more using public transport every day without seeing one, but then sometimes you get several in a row; it's just luck. Without a valid ticket or if you cannot show a ticket (e. g. you bought it with the HSL app, but your phone died), ticket inspectors can charge you an inspection fee of 80€ (in addition to the cost of a single ticket). The inspection fee is an invoice written in your name that you have to pay within a week. Legally, it is not a fine; ticket inspections are however authorized by a special Finnish law, which states that an unpaid fee can be forcibly recovered from you under distraint laws without a court order (like a fine). The same law authorizes inspectors to remove you from the vehicle, forcibly detain you and call the police in case you resist and/or your identity cannot be positively determined or there are reasons to doubt it. The inspection fee can be appealed against. Having a valid season ticket at the moment of inspection but not being able to show it (e. g. HSL card forgot at home) is one valid reason for the inspection fee cancellation.

Financing

Overall HSL budget is, as of 2019, about 750 million €, with incomes mostly 50/50 split between ticket sales and municipal subsidies, approximately split between municipalities according to real use. For 2019 69% of total ticket income has been estimated to come from AB-tickets, 14% from ABC-tickets, 10% from BC-tickets, and other ticket types share is 4% or below (actual figures are not yet available, because the new ticket zones have just been introduces this year). Inspection fees for 2019 have been estimated to amount to 5.2 million €, of which 1.8 million € have been predicted to be unenforceable and written off as credit loss.

As for municipal financing, Helsinki pays the most subsidies (180 million €), Espoo contributes 55 million, Vantaa 39 million, and all other HSL municipalities below 5 million each. HSL currently operates debt-free and has a large sum of cash on hand.

Most of HSL spendings are operation (~70%) and infrastructure (~20%) expenses. Perhaps surprisingly, operation expenses are dominated by buses, since those necessarily employ a large number of bus drivers, and as usual for Finland, personnel wage expenses are quite significant. Infrastructure expenses are more complicated; these generally include current maintenance and infrastructure depreciation, but not major new investments, which are generally financed by municipalities and/or state rather than HSL. Bus infrastructure expenses don't include road network maintenance, and commuter rail infrastructure expenses don't include track maintenance. Expenses as of 2019:

| Operation | Infrastructure | |

|---|---|---|

| Buses | 335M€ | 9M€ |

| Trams | 56M€ | 20M€ |

| Metro | 44M€ | 115M€ |

| Commuter rail | 95M€ | 20M€ |

| Ferry | 5M€ | <1M€ |

Within inner city: trams and car use limitations

Helsinki inner city public transport is mostly represented by trams, which form a rather dense network and have low intervals; there are of course some buses as well, and the metro line provides a southwest-northeast connection. The inner city is seen by city planners and HSL as a place where car use should be particularly discouraged. The street network capacity is limited; there are few wide streets, and the amount of historical buildings makes large-scale redevelopments not feasible. Although in the 1960s there were plans for multiple motorways through the heart of Helsinki, these were (thankfully!) abandoned with the 1970s oil crisis. The same crisis prevented the shutdown of tram network, although there were plans for it, and for example in the city of Turku such plans were carried out. Ever since then, there has been a strong focus on public transport use in the inner city.

Among the measures meant to reduce car use are:

- Low speed limits in the inner city (30-40 km/h)

- Many dedicated bus lanes and tram tracks, especially on bigger streets

- Reduced amount of car lanes due to these bus lanes and tram tracks (e. g. Mannerheimintie, the main road into the center from the northwest, while rather wide, has only one lane for cars in every direction in many places)

- All street parking in the inner city is tolled (and expensive), or time-limited to a short period, or sometimes both tolled and time-limited. (Inner city residents can get a street parking permit for their area and park for free, but of course they're not guaranteed a free curbside parking place. Delivery vans etc. can get a commercial permit.)

- Off-street parking is available but similarly expensive. Parking in an underground garage in Helsinki center can cost over 30€ for a single day, or over 300€ for a month, making this a very unattractive option for all but the most dedicated of car users

- Outside of the inner city, metro and train stations have sizeable park-and-ride parking lots. Allowed time varies from 10 to 24 hours. Park-and-ride facilities closer to the inner city, especially along the metro line, can cost 1-4€ per day; further out they are free

- Biking is promoted as another alternative to car use. Finnish city planning, not limited to Helsinki area, traditionally emphasizes pedestrian and biking connections; there are bike lanes and tracks in the inner city, and outside of it it is usually possible to bike entirely on wide sidewalks and park tracks. Bikes can be carried on metro and commuter trains, and there are bike parking areas at stations. While Helsinki doesn't have a perfect climate for biking, and bike use greatly decreases in winter, a significant portion of bike users still bike throughout the year. City bike rental stations, introduced by HSL relatively recently, also proved extremely popular

The measures do have significant effect on both car ownership and car use. Finland is traditionally a heavily automobilized country, largely because of sparse population density. As of 2016, 26% of all Finnish households were car-less; 74% had at least one car, and about 20% had two or more cars. As of 2012, the car-less percentage in Helsinki was 53% and in Espoo/Vantaa 33%. Of course, the car-less percentage is the greatest for single people and the lowest for families with children.

However, in any case many car owners use their cars mostly for shopping trips, recreation, etc. These are mostly uncontroversial (and for example on Sundays most street parking in the city is completely unlimited), and car use reduction is rather targeted at commuting trips, especially to the inner city. HSL collects statistics that shows that this goal has generally been achieved pretty well. Capital region population is growing by 10-15,000 people yearly, but the share and the absolute number of car trips into the inner city are dropping. Over 2007-2017 amount of daily car trips into the inner city dropped by 42,000 (11%), and of car trips into the very city center by 51,000 (20%).

Overall as of 2017, on an autumn weekday, 736,000 people were counted as travelling into or out of the Helsinki center. 28.5% used cars, 67.9% used public transport, and 3.6% were biking.

For comparison, such calculations were also made for "crosswise" trips, between western and eastern parts of Helsinki outside of the inner city. Public transport density there is worse developed overall, and making a trip by public transport often would require multiple transfers. So for "crosswise" trips across the line extending northwards from the inner city, only 18% used public transport and the rest used cars (biking frequency was not measured). However overall only 250,000 such "crosswise" trips were made, so this is a much less busy direction. Nonetheless efforts to improve crosswise connections continue, mostly in the form of bus "trunk routes".

Outside inner city: trunk routes

Outside the inner city population density is mostly much lower. The main idea of public transport planning there is to provide a few trunk routes with as large capacity and short intervals as possible. These trunk routes are railroads, metro and certain bus routes. People living outside walking distance from trunk routes can reach them by bus (also by bike or by car, using a park-and-ride parking in the latter case). Bus terminals are built next to the most important railway and metro stations.

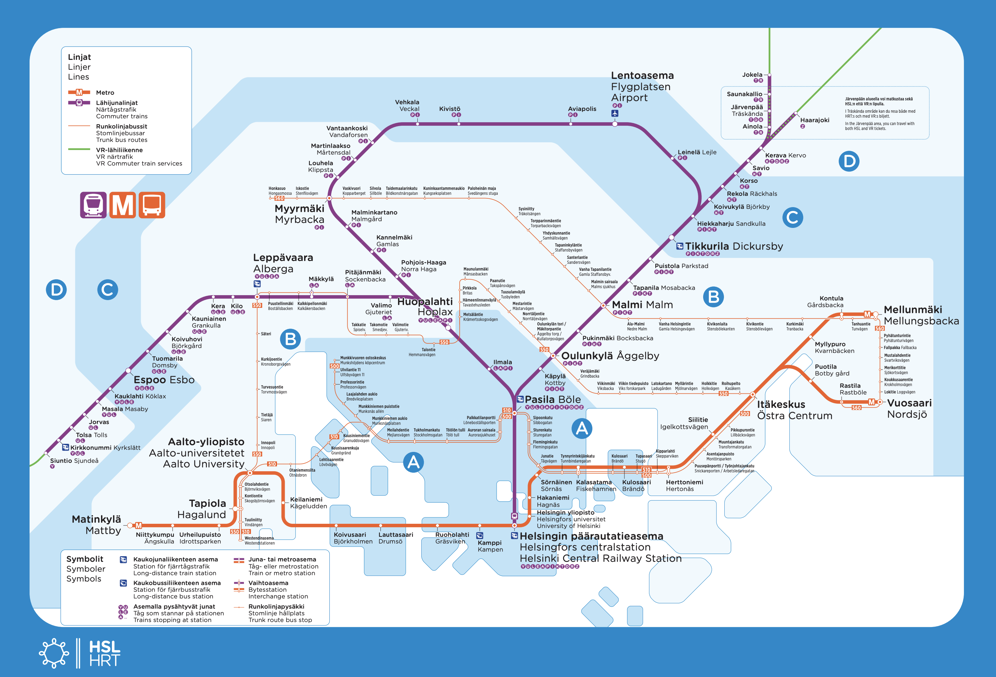

Railroads connect Helsinki inner city with northern Helsinki, central Espoo and large parts of Vantaa. Kerava and Kirkkonummi towns of Greater Helsinki are also reachable by commuter rail. Major bus terminals are built in Leppävaara in Espoo and Tikkurila in Vantaa. Smaller ones exist for example in Espoon keskus in Espoo, in Malmi in Helsinki, in Kirkkonummi and Kerava. Commuter rail also provides a connection to the Helsinki airport in Vantaa.

Metro has currenly only a single line, with a small fork at the eastern end. It runs from south Espoo, through Helsinki center, to eastern Helsinki. In Espoo railroad and metro line are parallel to each other, but run at about 5 km distance between them. Metro of course is often more convenient to use than trains (less interference from weather and long-distance trains) and has shorter intervals. Major bus terminals at metro stations exist at Matinkylä and Tapiola in Espoo, Kamppi in Helsinki center, and Itäkeskus in eastern Helsinki.

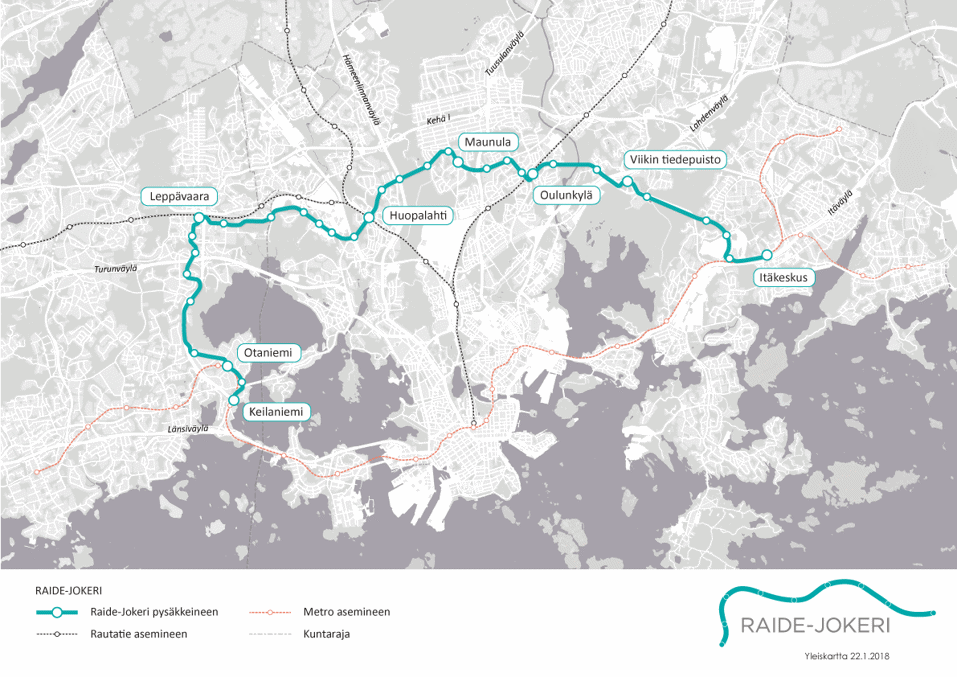

Trunk buses are used for crosswise connection. The most important one and the first such route launched is the bus 550, running roughly parallel to Kehä I, the inner ring road of the capital region. A few others were opened later. Unlike regular buses, trunk buses don't have ticket checks at entrance, run at very frequent intervals and sometimes use roads and connections reserved for them specifically. They however use same vehicles as regular buses, although differently colored (orange instead of blue).

Such buses are thus a form of bus rapid transit (BRT), although not a very advanced one. Bus 550 proved so popular that it is now being converted into a light rail line (Raide-Jokeri), the first project of its kind in Finland. The construction however has been started only in summer 2019, and will last five years.

Commuter train and trunk bus intervals within capital region are normally 5-10 min (on workdays, between approximately 07-19; somewhat bigger on other times). Commuter trains in most of Espoo are an exception, with 15 min intervals. Metro intervals reach 2.5 min at best.

The capital region tends to grow along railroads and the metro; in some cases it's the tracks that came first, in some cases it were population centers. Multi-storied buildings naturally cluster around railway and metro stations, and housing prices there are the highest. However not all major population centers in the capital region have trunk route connections, not yet at least. Most significantly, southwestern Espoo (Kivenlahti area) is still waiting for its metro line. This haven't necessarily been a bad thing for the inhabitants of these areas, as they tend to have straighter bus connections to central Helsinki instead; not everybody enjoys having a connecting bus to metro/train transfer.

Car use outside city center is pretty convenient. There are two ring roads (Kehä I and Kehä III), and a total of six of motorways or motorway-like radial roads leading away from the inner city, with 80-100 km/h speed limits. Regular streets with traffic lights and pedestrian crossings, on the other hand, have 40-50 km/h limits, and residential streets have 30-40 km/h. Parking, while free and generally easily available, is usually still time-limited though, so people working outside the inner city and commuting by car still often need some other arrangement than just street parking.

Other considerations

Accessibility is a major concern for all public transport operations in Helsinki area. Currently all modes of transport (excluding some regional buses and older regional trains) are accessible for wheelchair users, and use partially low-level vehicles. Commuter and metro trains have special doors in the middle which extend a small step filling the gap between the platform and the train. In case of buses and trams, the driver can provide assistance if necessary. Metro and train stations have elevators for direct access to platforms wherever necessary. (Those can also be used for bikes.) As far as I am aware of, all metro and train (wherever necessary) stations in HSL area have elevators.

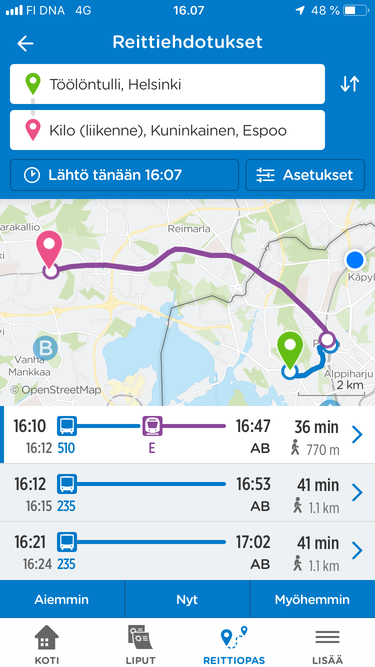

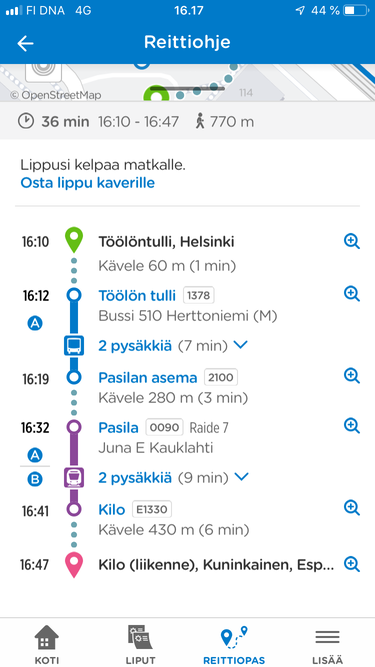

For route finding, the official HSL app or the online route finder reittiopas.hsl.fi can be used. They are quite featureful, and can look up a route with any transfers and at any time of day. There are extensive settings, including preferred modes of transport, walking speed and preference, ticket zones, specific routes to avoid and so on. As an added bonus, the route finder can look up walking and biking routes, and routes made partially by car and including park-and-ride facilities.

Real-time traffic information is also available at the application and on the Reittiopas page, and also at some stops and stations. In case of more important stops and stations there can be displays showing several next arrivals; time shown with a "~" means according to the timetable, and without one means real-time information. At smaller stops there can be a somewhat archaic looking small LCD display showing a few next arrivals in a loop. Most minor bus stops outside inner city don't have any displays.

Timetable information is still generally provided at most stops, although sometimes it can be in a form of a pretty small sheet. If there's space however, then usually also a map of the nearby area is also shown. In case of train and metro stations, schemes of their platform layout are usually also provided. Even regular bus stop signs have a fair bit of useful information on them.

Working hours for public transport are generally from 05-06 in the morning to 00-01 at night, depending on the particular route. On Friday and Saturday nights, and also in case of major events (concerts, sports games etc.) in Helsinki, hours are prolonged. Very late in the evening and very early in the morning there might be alternate routes, e. g. for trains. Night service is provided by some sparse bus routes (with N letter in the name) at times when no other transport is operating, so being completely stranded at night is unlikely. Night buses use same tickets and tariffs as regular ones.

Neighborhood routes are another special uncommon kinds of bus routes, providing services especially for elderly and disabled people, with very circuitous and slow routes stopping close to many possible locations of interest, and using mini-buses. There are no restrictions or special fees for using these routes by anyone, same as with night buses.

HSL public transport virtually never has any significant problems with safety or cleanliness. There are no homeless people, etc. (there are generally extremely few homeless people in Finland). At worst there might be annoying drunk people very late in the evening, especially on Friday and Saturday. Obviously that's not an absolute rule and very rarely exceptional situations may arise even in the safest place in the world. There are guards/conductors in metro and commuter trains, particularly in the evening. As most of Finland is, HSL public transport and its infrastructure is quite clean, which is not to say there can't be cigarette butts or a very occasional piece of trash or something like that. Some older infrastructure, particularly in the center, can look dated and somewhat shabby.

Stops, stations and vehicles can have some advertisement spaces but generally a fairly limited amount, a long way from any visual overload. Whole-body vehicle ads are quite rare and seem to only appear on trams and rarely on metro trains. Overall this is a fairly minor source of income for transport operators.

In summer (mid-June to mid-August), when students have their summer break and adults often leave for long vacations, public transport has summer schedules. This in practice means a bit longer intervals for some routes, including metro and trams. Some bus routes can be changed or cancelled for summer, but not many, mostly in outer suburbs.

Common problems and complains about Helsinki public transport

Nothing is of course ever perfect, and neither is HSL public transport.

A big theme of complaints in recent years have been changes to buses in light of the Western Metro launch. Helsinki Metro got its long awaited extension to southern Espoo in 2017 (Western Metro, Länsimetro), but it hasn't turned out to be such a good thing for everyone. Southern Espoo was before mostly served by straight buses to Helsinki center, running along Western Highway (Länsiväylä, Road 51), a motorway leading directly into central Helsinki. With the completion of the first phase of Western Metro expansion, buses were rerouted to the new metro stations. For many people this meant an extra change and longer time en route. Complaints were strong enough that HSL eventually brought back some of the older buses, but still only a few routes for rush hours. This is the common mode of operation for HSL, and the same thing happened before with metro construction in eastern Helsinki, in the 1980s. The problem may subside somewhat when the rest of the Western Metro will be finished.

The punctuality of HSL transport sometimes leaves a lot to be desired. Few minutes delays are very common and perhaps not a huge problem, but sometimes, especially during snowfalls and other poor weather the delays can be much bigger. Buses leaving earlier than they should, or being cancelled outright, is also quite annoying and happens sometimes. HSL doesn't provide any compensations for delays or cancellations.

In general weather sometimes gives the public transport a bit of trouble. This autumn for example the metro at the central railway station was flooded in heavy rains. It was operational again soon enough but the elevators have been out of order ever since.

Crosswise connections, despite all measures to improve them (bus trunk routes mostly), still remain fairly slow. Even going between major bus terminals such as for example Matinkylä and Leppävaara takes significantly longer than it would seem it should, and the routes are not exactly very straight.

Ticket sale through HSL app was previously sometimes unstable, and loading tickets/value onto a HSL card is still impossible to do online, although it has been promised for a long time.

Major recent and upcoming projects

Here are some major infrastructure projects of recent past and near future related to public transport in Helsinki area. As you can notice from the "timetable" and "cost" notes, construction on this scale is slow and expensive business. Infrastructure investments proved particularly difficult for municipal budgets of Espoo and Vantaa, both of which are nowhere as rich as Helsinki and have lower tax income per capita. Both Espoo and Vantaa are significantly indebted at this point, and it is expected that after finishing projects from this list they would take a long breather.

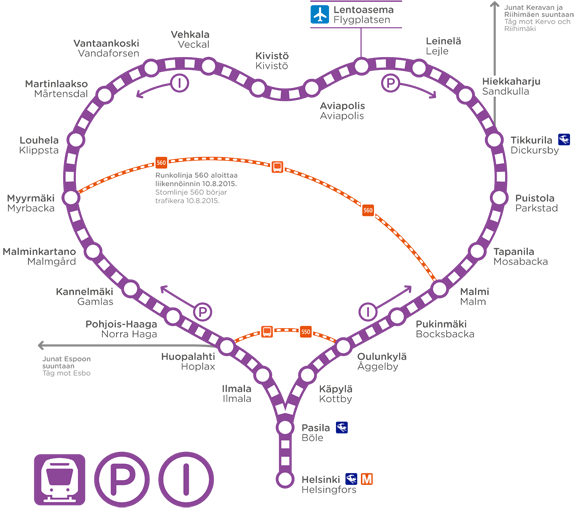

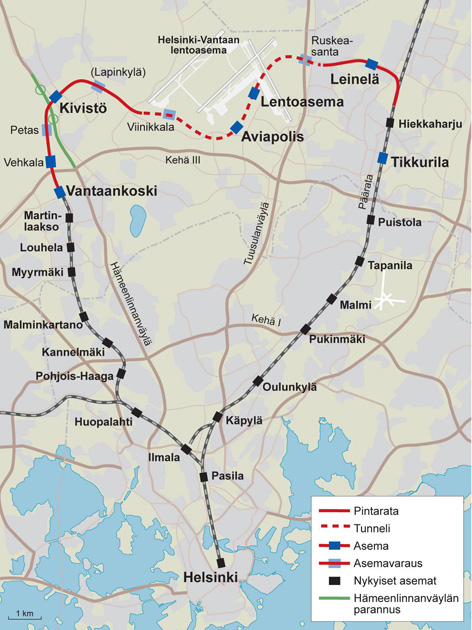

Ring Railroad (Kehärata, Finished)

The Ring Railroad (Kehärata) is the newest major rail project in Finland, a 18 km of new double track railroad in Vantaa connecting the two old main rail lines, the Main and the Coast railroad. At the western end, Ring Railroad extended the older dead-end Vantaanlaakso line, branching from the Coast Railroad at Huopalahti, built in 1975 for a commuter train connection with western Vantaa. At the eastern end, Ring Railroad joins the Main Railroad at Hiekkaharju near Tikkurila in eastern Vantaa. Between Vantaanlaakso and Hiekkaharju the new line serves some newer Vantaa neighborhoods (like Kivistö) and more importantly, the Helsinki-Vantaa airport.

The Airport (Lentoasema) station has a direct exit into the airport building, and the only way to accomplish this was with a huge, 8 km tunnel underneath the entire airport area. Airport and the nearby Aviapolis are both underground stations, the first of their kind in Finland, built at 40 m depth. In practice they look and function a lot like metro stations. Apart from these two underground stations there are three surface ones, and reservations for four more.

The trains going to the airport are not some special airport trains, but just regular commuter trains under routes I/P, and serve both airport passengers and regular commuters using regular tickets and tariffs. Both of them make a complete loop from Helsinki central station to the airport and back, just in different directions (P clockwise and I counterclockwise). In either direction a trip from Helsinki to the airport takes about half an hour. Trains run between about 04:30 and 01:30, with 10-30 min intervals. I/P-trains also replaced the earlier M-train route of its predecessor, the Vantaanlaakso Railroad.

Long-distance trains do not use this track, but it is possible to buy a long-distance train ticket with "Helsinki Lentoasema" destination, which would include the transfer to I/P commuter train. Allegro international train passengers coming from Russia can also freely transfer to an I-train under their Allegro ticket from Tikkurila station.

A residential area for 30,000 inhabitants is under construction near the Kivistö station of this line, and a commercial area at the Aviapolis station is expected to attract as many as 50,000 jobs.

Timetable: Approved in 2005, constructed started in 2008, in operation 2015

Cost: 774M€

Paid by: 50% Vantaa city, 50% state. 18M€ EU support

Western Metro (Länsimetro, Partially finished)

The Western Metro (Länsimetro) was probably the most awaited project in the history of the capital region. A 21 km western extension of the existing Helsinki metro, it has been planned to link together all the population centers of southern Espoo: Tapiola, Matinkylä and Kivenlahti. Currently the first phase (to Tapiola and Matinkylä) is finished and the second one (to Kivenlahti) is still under construction.

The western extension was envisioned in some shape for decades, and the specific alignment to Matinkylä was planned since 1998. Espoo council approved the project in 2006, and the first phase of construction began in 2008. The city of Espoo has been bearing most of the massive cost. Opening of the first phase was planned for January 2016, but met repeated delays. Finally Western Metro was launched in November 2017.

The first phase includes 8 stations and is 14 km long. Two of the stations are in Helsinki on the big Lauttasaari island, and the rest are in Espoo. The alignment is not entirely straight but makes a small detour to Aalto University in Otaniemi area. Skipping it could have made metro a little faster, but the university is a pretty major destination. Although much of Espoo is not especially dense, it was decided to build the entire western extension underground and not above ground (unlike the old metro), to avoid claiming too much land and making road traffic etc. more awkward. Western Metro stations are generally nicer looking than old ones, although they all look pretty similar with just decorations varying. To accomodate new travellers HSL bought 20 new metro trains (M300 series) and shortened rush hour intervals from 4 min to 2.5 min.

The Western Metro didn't exactly make everyone happy. As mentioned before, southern Espoo was formerly served by direct bus routes along the West Highway (Länsiväylä) to Kamppi bus terminal in Helsinki center. These were quite convenient for many. After the Western Metro was opened, Espoo buses were rerouted to the new bus terminals at Tapiola and Matinkylä stations (in Ainoa and Iso Omena malls), adding an extra transfer and making the overall travel time actually longer for some. The backlash was strong enough that HSL eventually had to return some bus routes for rush hours, at least until the second phase of the metro will be finished.

Nonetheless the Western Metro is here to stay, and now forms the axis for the further development of Espoo. While Tapiola, Matinkylä and Kivenlahti already were established population centers, there is currently a lot of residential and commercial construction going on near most other stations. Aalto University in Otaniemi and a high-rise office area in Keilaniemi also got properly connected to the public transport system.

The construction of the second phase of the project is still ongoing, and planned to finish in 2023. It would include five more stations and a metro depot at Sammalvuori, which would be the second depot of the overall metro system.

Timetable: Approved in 2006, first phase built in 2009-2017, second phase started in 2014, estimated to finish in 2023

Cost: 1st phase 1186M€, 2nd phase 1158M€, total 2344M€

Paid by: 85% Espoo city, 15% Helsinki city. 30% state aid

Pasila Station (Mostly finished)

Pasila is an area of the Helsinki inner city north of the center, and Pasila railway station is the first station after the Helsinki central station, in about 3 km away from it. All trains, except international ones, stop at Pasila, and the two principal railroad directions (Main and Coast Railroad) split only immediately after Pasila. It is both a very important transfer station, and a major destination in its own right, with a lot of offices, especially government ones. There is also a residential area, a stadium, an exhibition center, the main passenger car depot of Finland at Ilmala, and a car-loading station for night trains going to Lapland.

Pasila used to also have a major freight station, but all freight operations there were gradually stopped, when cargo harbors were moved from central Helsinki to Vuosaari at the eastern outskirts of the city, and harbor railroads were dismantled. (In fact, there are no freight railroad operations anywhere within Kehä III road anymore.) The freed up areas were planned for massive redevelopment.

The first redeveloped part to be finished is the new Pasila station, combined with the Mall of Tripla shopping center. This is the fourth incarnation of the Pasila station already. The previous one was built only in 1990. A temporary station was built in 2016-2017, then the old station shut down and was dismantled. The new station was built on its foundations and opened in October 2019; the temporary station is in turn being dismantled now. The new station is pretty much just a wing of the Tripla shopping center, the bulk of which is situated west of the tracks. The 1990 station, 2017 temporary station and Tripla station are all situated above all 10 tracks, with escalators and elevators down to platforms.

More Pasila public transport-related development came with Tripla. The 11th, westernmost track was constructed, with a new platform for it. Only 1.5 km of new track cost about 50 million €, as it necessitated construction of new bridges, changing switch configuration of other tracks, and also in general all kinds of works in tight squeezed spaces that had to avoid any interference with all regular trains. The track is meant to give more track capacity for commuter trains in Coast Railway direction, cleanly separating them long-distance trains, and reducing possibility of late trains. The new track is in use since November 2019, some works are still ongoing.

In front of the Pasila station and now also the Mall of Tripla there is a large road overpass that has also mostly been rebuilt as a bus and tram terminal, so that you can get onto a tram or bus (including trunk buses) very quickly just by exiting the station. For cars, a disused tunnel under tracks south of Pasila, formerly used for a harbor railroad, has been expanded and converted into a car tunnel.

Some space under Tripla has also been excavated and reserved for a possible station of the future second metro line. It is not at all certain that the line would be constructed at all, or that it would go through Pasila, but the likelihood is big enough that this was done now; later on costs to add it on top (or rather, on bottom) of everything else would be many times greater.

Development of the Mall of Tripla and the rest of Pasila continues. Hotel, office and residential parts of Tripla hasn't opened yet, only the station and the shopping center. Construction at other areas of the former freight station is ongoing. Overall, unlike all others projects mentioned here this one has mostly had private financing, and at least from quick googling and research it's not clear exactly how much went to actual traffic infrastructure vs. how much went to commercial real estate, particularly since in case of this project it's not easy to distinguish them. In any case the total price tag for Mall of Tripla is quite colossal at 1.2 billion €. This has been the second most expensive single construction project in the history of Finland, after the new unit of the Olkiluoto nuclear plant.

Timetable: Approved and construction started in 2014, temporary station in use 2017-2019, new station and most related public transport arrangements opened in 2019, some works still ongoing

Cost: 1.2B€ for station and Mall of Tripla. 49M€ for the extra 11th track

Paid by: Mostly private financing, except railroad parts. Ownership of the plot and the public areas of the station also bought out by YIT (prime contractor) by 137M€

Raide-Jokeri Light Rail (Under construction)

Raide-Jokeri is a project for a 25 km long light rail line (fast tram) meant to replace current trunk bus route 550. Jokeri name was used previously for the original bus 550, and means JOukkoliikenteen KEhämäinen RunkolInja (Public Transport Circular Trunk Line). Raide means simply "track".

True to its name, bus 550 has had a semi-circular route around Helsinki, roughly following the Kehä I ring road, but passing through residential and commercial areas instead of just the highway. It was the first bus "trunk route" of HSL, with short intervals and some right-of-way advantages, and has been popular enough that Raide-Jokeri was eventually devised to replace it. In fact, a light rail line was the original idea for this route in the 1990s, but it was rejected (or rather, moved to plans for the 2030s) due to being too expensive. The demand for the bus 550 grew faster than expected, however.

Raide-Jokeri would use the same 1000 km track as Helsinki trams, but would have no connection with the existing tram network, and would use a new depot and different rolling stock. 29 Artic XL trams were ordered from Transtech plant at Kajaani in East Finland for the Raide-Jokeri. These are based on existing Artic trams in use in Helsinki, but are longer (34 m with four articulation points) and bi-directional. There would be 34 stops, placed at about 800 m intervals. Timetable intervals are expected to be 5-10 min. Trams will not in fact be particularly fast, and might be somewhat slower than buses even (Raide-Jokeri has been mocked as "a slow tram marketed as a fast tram"), but still would have an advantage of greater capacity and own right-of-way.

Works on Raide-Jokeri started in summer 2019, in many places at once along the entire route. Nonetheless the construction is expected to take five years. A mostly completely new track alignment must pass through densely-built areas, requiring a lot of moving of existing communications, a lot of earthworks, and a lot of bridges (and even one tunnel) have to be constructed. Quite a few streets are at the moment closed due to Raide-Jokeri construction, affecting among other things the current bus 550 route.

Timetable: Approved in 2016, construction started in 2019, estimated to finish in 2024

Cost: 386M€ according to current estimate, including rolling stock (92.5M€ for 29 pcs.) and depot

Paid by: ~45% Helsinki city, ~25% Espoo city, ~30% state aid

Espoo City Railroad (Construction upcoming)

Espoo City Railroad (Espoon kaupunkirata) is the extension of the 3rd and the 4th rail track of the Coast Railroad from Leppävaara, where they currently end, to Kauklahti on the western edge of Espoo. It would be about 14 km long. Although the Main Railroad has at least four tracks all the way to Kerava (29 km), where commuter train services currently end, the Coast Railroad is currently lacking in that regard.

Espoo City Railroad, if constructed, would improve intervals between Kauklahti and Leppävaara from 15 to 10 minutes, and between Kirkkonummi and Kauklahti from 30 to 20 minutes. Travel times from most stations to Helsinki would have been reduced by about 6 minutes. It would have also improved accuracy and reduced routine delays for both commuter trains and long-distance trains to Turku; the current track is at its capacity limits and minor delays are quite common. Almost all stations on the stretch would have been rebuilt. A-train route would have been abolished as unnecessary and E-train would take its place.

The project is also a prerequirement for building the so-cased ELSA-railroad (Espoo-Lohja-SAlo), a completely new alighment for Turku trains, reducing travel time considerably and also bringing commuter rail to the city of Lohja.

The project has been in planning for considerable time. General plans and feasibility studies are finished and it awaits green light from the municipality and the government. At the moment this project seems to have very good perspectives.

The existing 81 Sm5 commuter trains fleet will not be enough to serve the entire Helsinki area once the Espoo City Railroad will be finished. As of November 2019 HSL is preparting for procurement of more trains (30-40). Their models or manufacturers will have to be determined. A new depot will also be necessary, as there is no space to expand the Ilmala depot anymore. There is no rush; a decision on new trains and depot will be made by the end of 2020, and the actual trains would arrive only in 2025 or so.

Timetable: Planning and feasibility studies finished. Awaiting approval, expected in near future. From that point can be constructed and opened in 4-5 years

Cost: 275M€ according to current estimate. Does not include train procurement costs, which is done independently of this project

Paid by: Presumably Espoo city and state aid

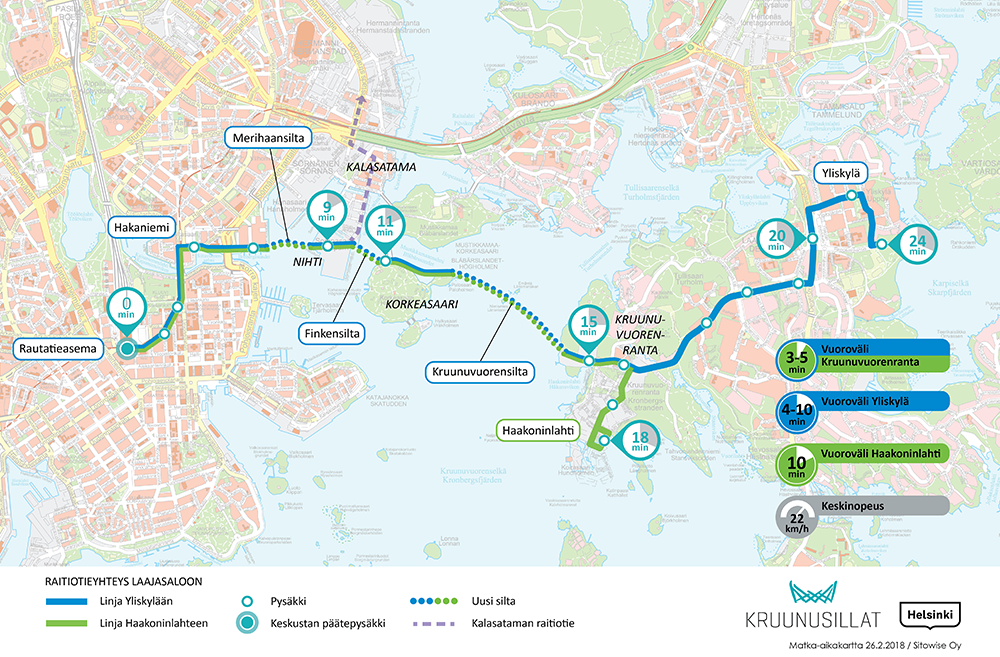

Crown Bridges (Kruununsillat, Construction upcoming)

The Crown Bridges (Kruununsillat) are a project to extend Helsinki inner city tram network to the east. The bridges would be three bridges, the longest one 1200 m long (which would make it the longest in Finland), from Merihaka northeast of Helsinki center to Laajasalo, a large island of eastern Helsinki, connected to the mainland with a small bridge in the north and currently only having buses. The name comes from the sea area the big bridge would cross, Kruunuvuorenselkä (Crown Mountain Expanse), and the bridges would in particular serve the new neighboorhood of Kruunuvuorenranta (Crown Mountain Coast), in place of a former oil harbor. The Crown Mountain is just a low but steep and prominent rocky hill immediately on the coast of Laajasalo.

The bridges would only hold tram lines and pedestrian/biking tracks. Emergency services would also be able to drive on them but no car lanes are planned. Unlike Raide-Jokeri, this would be an extension of the existing tram network and would be built to the same standards and using same trams (although it would be necessary to procure more trams).

Apart from Laajasalo the project would bring a rail connection to the new neigborhood of Kalasatama in the inner city, and to Korkeasaari zoo. In total 10 km of tram track would be constructed

Timetable: Planning and feasibility studies finished. Approved by Helsinki city. Design phase started. Construction expected to start in 2021 and end in 2026

Cost: 359M€ according to current estimate, including about 100M€ for new trams

Paid by: Presumably Helsinki city

Sipoo Rail Connection (In planning)

Sipoo is a mostly rural municipality east of Helsinki, with a few bigger villages which now get apartment building areas due to closeness to Helsinki. Sipoo is a HSL area municipality but currently only served by buses.

The largest Sipoo village and the municipal center is Nikkilä, with a population of probably about 7000 or so (it doesn't form an own municipality or urban area so no precise figures are available), which is projected to grow rapidly. Normally it still would be far too small for a new rail connection, but it so happens that a railroad there already exists, a freight line from Kerava to an oil refinery in Sköldvik passing through Nikkilä. That railroad is in good condition, and Nikkilä is only 10 km down that railroad from Kerava. Therefore extending at least some commuter trains from Kerava to Nikkilä would not be a particularly huge project.

Nonetheless trains cannot be launched right now; some works are still necessary, mostly just constructing passenger infrastructure at Nikkilä station, and replacing existing level crossings between Kerava and Nikkilä with overpasses. According to modern standards, new lines with frequent commuter train services must not have any level crossings. Still, investments would be quite minor compared to pretty much any railroad construction project.

It is expected that trains could go to Nikkilä with 20 min intervals in rush hours and 40 min intervals outside them. Apart from Nikkilä, two other stations would be opened on the line. Travel time between Nikkilä and Helsinki would improve from current 48-56 min to 36-37 min.

Timetable: Planning and feasibility studies finished. Not approved yet. Could be constructed in early 2020s

Cost: 31M€ according to current estimate

Paid by: Sipoo and Kerava municipalities, state aid

Drop Railroad (Pisararata, In planning)

Drop Railroad ("drop" as in raindrop, Pisararata) is quite an unusual project. The basic idea is easy to understand from just looking at the map though. Commuter trains, some or all, instead of going to Helsinki central station, would go from Pasila to a teardrop-shaped underground tunnel, with three stations, one of them at the same place as the current aboveground station. In this way a lot more rail capacity for commuter, regional and long-distance trains could have been sustained in central Helsinki.

The project is quite extreme. It would include 8 km of new track, of which 6 km in a tunnel, which would go underneath the very center of Helsinki, stuffed with all kinds of existing tunnels and communications. Costs are estimated to be at least almost 1 billion €. It is not clear what the new train routes would be, and studies suggest that a lot of new infrastructure apart from the Pisara-rata proper would be necessary to actually realize the benefits. State financing was already denied once in 2015. Still the preliminary planning and discussions of the project are ongoing, and HSL considers it vital for further development.

Timetable: Some planning and feasibility studies done. Not approved yet, not at all certain to be approved. Timetable unclear, nationwide political decisions necessary. In best case would be constructed in late 2020s

Cost: 956M according to current estimate

Paid by: Mostly the state, also Helsinki city

Possible future projects

All these projects are in early planning stages, and at best work could begin only in late 2020s. Few details other than preliminary plannings and estimations have been done yet. It is not at all certain that any of these projects will be completed at all.

- Eastern Metro (Itämetro). Extension of the existing metro line to the east. Current Helsinki master plan provides for massive construction in Östersundom in the far east of Helsinki beyond Kehä III, currenly an almost completely rural area. Eastern Metro with several new stations would be the trunk connection for Östersundom. It would be shorter than the Western Metro and partially above ground. Both Östersundom construction and Eastern Metro construction would not start until at least 2025, but still make good sense and have the best chances of succeeding out of this list. However the master plan for Östersundom has repeatedly encountered difficulties in regard to numerous protected nature areas there, including the Sipoonkorpi National Park

- Second metro line. Most likely would go north from Helsinki center. Numerous alignments have been proposed over the years, some reservations are made on master plans, and some stub tunnels and halls even exist in a few places, including Pasila. However the project hasn't been discussed in a long time, and no attempts for even rough planning have been made. May be built some time in 2030s at best

- Airport Railroad (Lentorata) is another project of a rail connection to the Helsinki-Vantaa airport. Instead of a loop route, like the current Ring Railroad has, it is planned to go straight, underground from Pasila, under the airport, and re-emerging at Kerava. It would also have a different function, carrying mostly long-distance and regional trains, not commuter ones. These trains could be sped up by as much as 20 minutes. The track would still of course have influence on commuter train timetables, namely those could become more frequent. Cost estimates are massive (2.65B€)

- New higher-speed long-distance connections: Finland Railroad (Suomi-rata), an upgrade of the Main Railroad allowing a higher speed connection to Tampere; one-hour Turku train (Turun tunnin juna), a faster connection to Turku partially replacing the Coast Railroad; Eastern Railroad (Itärata), a completely new rail connection to the east of Finland, most likely through Porvoo. All of these would be extremely expensive and advantages fairly marginal; preliminary studies suggest low economic profitabilities for all of tem. Could still be realized given enough political will, but probably no earlier than 2030s in any case. Although these are meant for long-distance trains, these would also allow more regional connections, for example to Porvoo and to Lohja

- Vantaa and Espoo light rail. Both Vantaa and Espoo have their own plans for light rail. For Vantaa the route under consideration is Mellunkylä-Airport, proving a crosswise connection across Vantaa. For Espoo the route would be Leppävaara-Kalajärvi, providing a trunk route for currently sparsely populated northern Espoo. In both cases the advantage against buses is not at all certain, in view of the massive costs of such projects and economies of Espoo and Vantaa already somewhat strained by existing infrastructure investments

This is all for the first part; in the second part we will look closer at individual kinds of transport, including their route schemes and a lot of outside and inside pictures.