The municipality of Gällivare (pronounced "yellivareh") is the second northernmost municipality in the inland part of North Sweden. With its vast 16,800 sq. km area it includes a good chunk of the Scandinavian Mountains, but the population is quite minor, at 17,600 people. Of these 10,300 live in the city of Gällivare proper, and about 4200 more in the nearby settlements of Malmberget and Koskullskulle.

This remote area was once inhabited only by the Sami people,and is in fact still divided into three mountain Sami and one forest Sami "village" (sameby). A lone, low mountain named Jiellovárre (Cracked Fell) by the Sami existed in the foothills of the Scandinavian Mountains. In the 1690s, some Per Andersson from Prästholm in Råneå, a place way down by the Bay of Bothnia, first discovered iron ore at Jiellovárre. It took quite a while to actually start at least exploratory mining, in 1735 by Captain Carl Johan Thingwall. Thus the history of Gällivare started. The mountain was initially knows as Illuvare in Swedish, then as Gällivare, and then as simply Malmberget (Ore Mountain), but the name Gällivare stuck for the whole area. It was not the first mine in North Sweden though; that honor belongs to Svappavaara even further in the north, where a copper mine, a fairly large one for the time and location, operated from 1664 until the 1700s; currently there is another iron mine at Svappavaara.

The early history of the iron mine was long and confused, with it changing owners many times. The ore deposit was huge and of the highest quality, but the problem, of course, is that it was in the middle of nowhere over the Arctic Circle, and iron ore is a bulky thing to transport. All attempted mine operations remained small until the end of the 19th century. The ore was generally transported by the local Sami people on reindeer sledges to smelters closer to the Bay of Bothnia and civilization; of course this was ridiculously inefficient.

The original idea of the new way to transport ore was developed in the middle of the 19th century, and it would involve combining that fancy new railroad thingy with more traditional canals. Despite the existence of the great Lule River right nearby, it was not suitable as a transport link, due to all rapids and waterfalls, which had not been even dammed yet. The canal from Luleå would bypass some of those and go to Storbacken near Vuollerim, and a railroad could be built from there onwards to the mine. The project was known as English Canal _(_Engelska kanalen)__, because the construction was managed by a British company. It started in 1863, and almost 1500 people worked on the construction, but still by 1867 the company went bankrupt and the canal remained unfinished (some traces apparently still remain).

The solution eventually came decades later, in 1888, when a railway, Ore Railroad (Maimbanan), was built all the way from Luleå to Gällivare. It was also built by a British company, and its standard was rather inadequate, so it got nationalized within a few years and modernized. The iron mines quickly began to grow, and soon afterwards mining also started in the area of Kiruna, farther north from Gällivare; by 1899 the railroad was extended to Kiruna, and by 1903 across the Scandinavian Mountains to the port of Narvik in Norway. Gällivare and Kiruna mines were eventually consolidated under one company, which came to be also nationalized in time, and is now known as LKAB (Luossavaara-Kiirunavaara Aktiebolag). The company is named after the two fells in Kiruna; indeed, the Kiruna mines are by now bigger and more important than the Gällivare one. And while both Gällivare and Kiruna are small mining cities, Kiruna is also significantly bigger and better known.

Nonetheless, iron ore is still being mined in Gällivare as well, or more properly, in Malmberget, where there is actually a huge open pit mine sticking in the middle of it. Gällivare proper, which was the part that I saw on my trip, is a more ordinary looking town, and nothing really reminds there of any mining. Unfortunately I didn't have the time to look at Malmberget as well. On the other hand as an added bonus, I've also got a few pictures of the Nattavaara village and station, another small locality on the Ore Railroad.

1. I ended up in Nattavaara because this was where I rented a house for this trip, for just two nights. It was dirt cheap, perhaps because Nattavaara is kind of in the middle of nowhere, in 50 km to Gällivare by road, with very little to see or do any closer (apart from the secondary entrance to Muddus National Park). Nattavaara actually consists of two villages; Nattavaara proper by the railway station, population slightly above 100, and Nattavaara by (Nattavaara Village), the older Nattavaara, population slightly below 100. The name is obviously Finnish in origin, and indeed Nattavaara was apparently originally founded by a Karelian settler. In general these lands are close enough to Finland that a large fraction of population have Finnish roots; Gällivare even has a Finnish version of the name, Jällivaara.

2. Nattavaara is known as one of the coldest localities in Sweden. On the previous picture you can see how it looked in the evening on one day, and on this one, in the morning on the following day. While I was aware that the weather was about to get worse, I didn't quite expect... that!

3. Nattavaara by school, near the house where I lived. It was late May, and obviously I already had my summer tires on, so I was pretty anxious to drive. Fortunately, the temperature was above freezing, and snow melted on the road surface rather than accumulating on it. Still I drove to Gällivare quite carefully. The road was paved and of good quality, but of course nearly devoid of any cars. Eventually the amount of snow began to decrease, and by the time I was in Gällivare there was no snow anymore.

4. So this is what central Gällivare looks like.

5. A very basic-looking town, although of course it probably would have looked friendlier in nicer weather.

6. Gällivare station, to which the town largely owns its existence.

7. Iron reindeers by the station. I didn't see any actual reindeers close to the town, but probably there are some.

8. Bus timetable by the station.

9. The station itself. There are passenger trains here, to be sure, but the Ore Railroad is vastly more important as a freight traffic link. It alone carries 44% of all Swedish railroad cargo shipments, and it carries more trans-border cargo to Norway than all other railroad links between Sweden and Norway combined. It is so important to Swedish economy that it was the first railroad electrified in Sweden (first section in 1915, and completed by 1923). The Lapland iron ore is just so big of a deal. And the whole Nazi Norwegian occupation was also largely related to securing ore shipments from the neutral Sweden.

10. 1313 km to Stockholm and 359 m above sea level, as the station boasts. The station is also where the barely used wilderness Inland Railroad (Inlandsbanan) ends.

11. A river called Vassaraälven flows through the southern part of the town. The Lule Sami name for the river is Váhtjerjåhkå, and the Lule Sami name for the town itself also comes from the river: Váhtjer. As you can see, the river turns into a snowmobile track in winter.

12. Although most of Gällivare grew only with the arrival of the railroad, there are a few siginificantly older buildings, and among them is the old church, also known as the Lapp church, or the Ettöreskyrkan, One Öre Church, named so because a special tax of just one öre (penny) in a year was levied on all households in Sweden to finance its construction, which was originally finished in 1754.

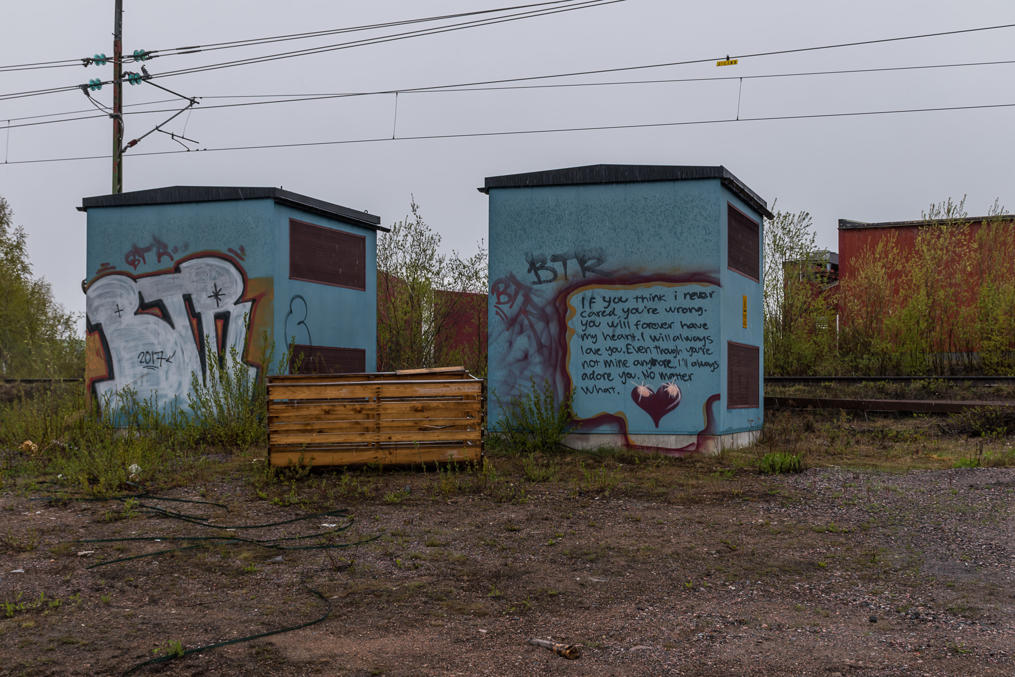

13. Gällivare romance.

14. Immediately to the southwest of Gällivare is another lone mountain, named Dundret (from Finnish tunturi, meaning simply Fell). It's quite high and prominent at 823 meters, but in this sort of weather there was no hope of seeing much of it. I didn't have the time to climb it either; it is quite possible, and you can even drive most of the way up (there is a road to skiing slopes). At least I could see the Fjällnäs mansion at the very foot of the mountain.

15. Fjällnäs is possibly the most beautiful building in Gällivare. Officially it's even called a "castle", Fjällnäs Slott. It was built in 1888 by Colonel Carl Otto Bergman, a local industrialist and a hugely influential man there at the time, known as the Norrbotten King. He was a co-founder of AB Gellivare Malmfält company, which took over the operation of the mine from the bankrupt British company, and also bought the Kiruna mines. AB Gellivare Malmfält came to backrupcy itself at the turn of the century, and was bought out by Trafik AB Grängesberg-Oxelösund industrial group. In 1957 the Swedish state bought out mines and spun them out as a separate state-owned company, LKAB, again.

16. You can just barely see the skiing slopes on Dundret.

17. Rapids on Vassaraälven.

18. There is a small open-air museum with a few historic buildings at the edge of the city.

19. It has some Sami constructions, like the familiar-looking njalla tiny storage barn for food, raised to prevent looting by animals.

20. Other buildings belonged to Swedish and Finnish settlers.

21.

22. Back to the downtown. This is a local city bus; Gällivare has a few, mostly running alone Gällivare-Malmberget-Koskulskulle route.

23.

24. Local pizza. Note the five-digit phone number.

25. The downtown.

26. New school and adult education center under construction, titled "Knowledge House".

27. The new church, built in 1882.

28. The old school building now houses a city museum. It was difficult to find an entrance, it is actually on the other side of the building. It has free entry and is worth a look.

29. A rather cool painting in the lobby shows the history of Gällivare (from the center outwards).

30. This is a picture of the pit of the Malmberget mine. As I understood, this all is planned, not some abrupt disaster. Obviously the houses close to the pit get bought out and the residents move. You might have heard that the city of Kiruna farther to the north is slowly being partially moved due to the expanding mine underneath. Same thing happens in Malmberget, but here the mine is apparently expands in an unremarkable detached house area, so it's not a particularly huge deal.

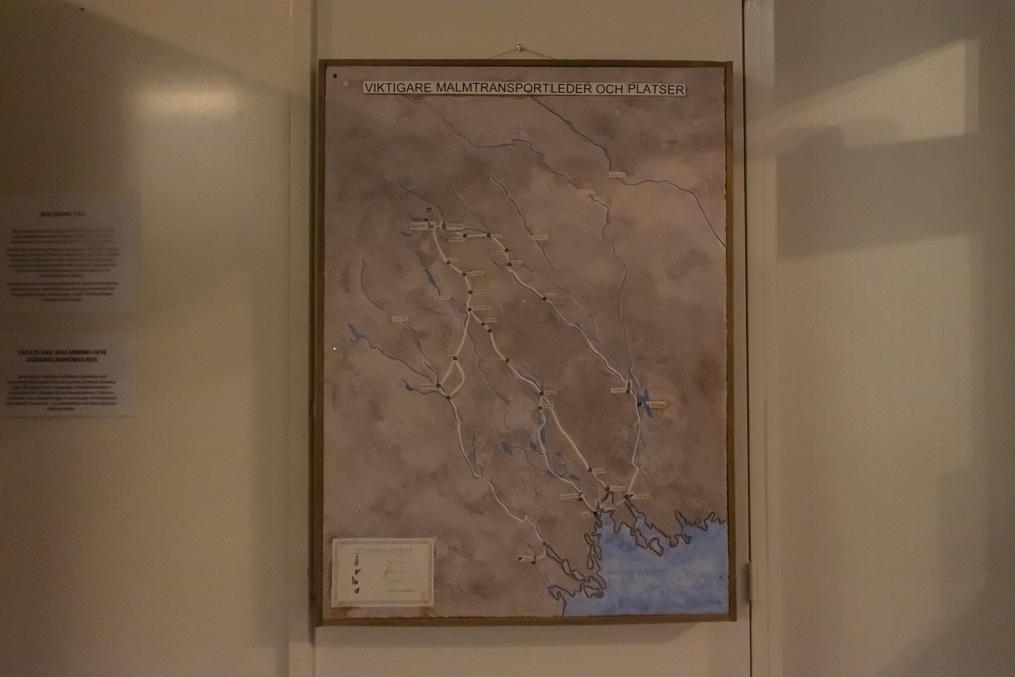

31. The old transport routes linking the mine with the seaport at Luleå before the railroad.

32. And the original mode of transport — an ackja reindeer sledge.

33. Railroad construction was done by navvy laborers, rallare in Swedish. The original service road used to move materials for the construction still runs alongside the railroad now, and is named Rallarvägen, Navvy Road. It is usable now as a hiking or biking track.

34. First ore train on the finished railroad.

35. Loading a modern ore train.

36. The museum of course also has a small section about the Sami people.

37. Sami tools.

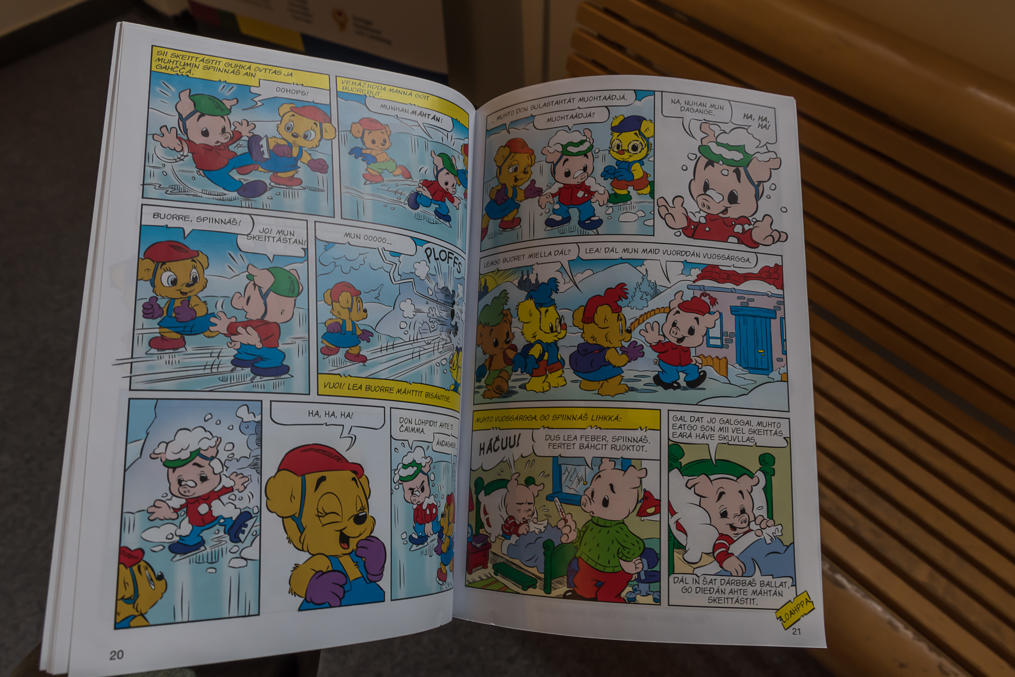

38. This one is an unexpected find: a Bamse kid comic book (those are Swedish in origin and rather popular in Sweden), translated into Sami! Now that's pretty cool! I think this is Northern Sami language though, while in Gällivare area Lule Sami would be more appropriate; but Northern Sami has a lot more speakers and it makes sense that more things would be translated into it than into Lule Sami.

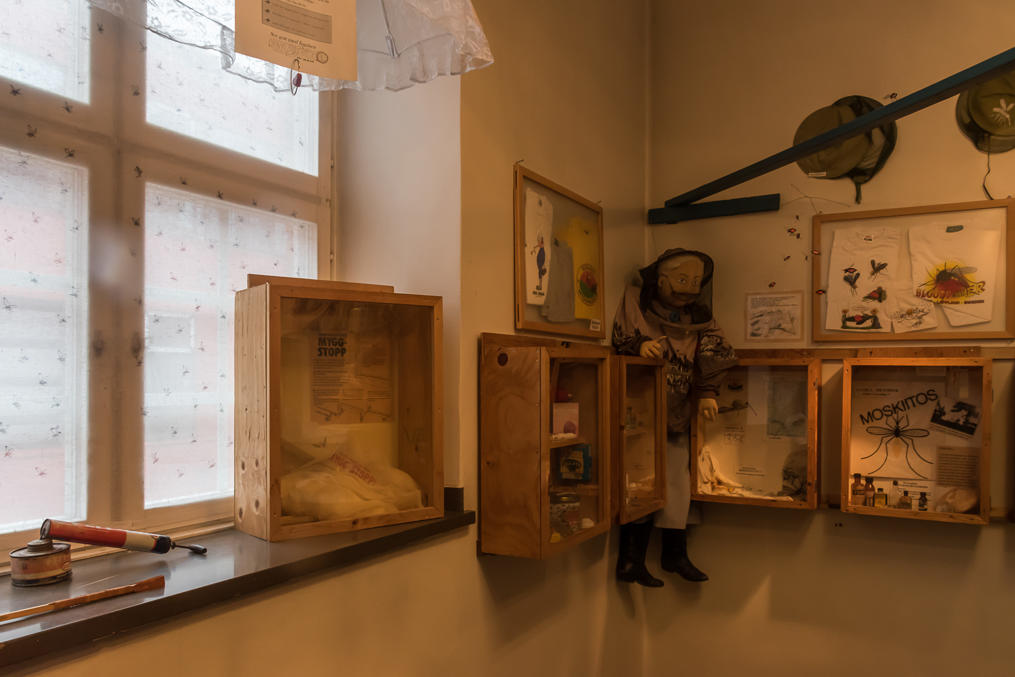

39. Funnily enough, a small section of the museum is exclusively about mosquitoes. The season when I visited was far too early for any mosquitoes, thankfully. They can get absolutely nightmarish in the north but their season is not especially long.

40. Outside of the museum.

41. Municipal administration building. Note the coat of arms in the right and near "Gällivare Kommun", with a reindeer and a Mars symbol, which of course in this context means an alchemical symbol of iron, rather than anything to do with males.

42.

43. I really struggle to write anything of substance about the views of the downtown, because it's really just so ordinary. I don't mean that in a bad way though; Gällivare is certainly nice enough for a 10,000 mining town in the middle of nowhere in the Arctic.

44. One thing I can criticize is that quite a few of the roads in the city were quite poor. Well, in places they still haven't even collected crushed rock from sidewalks from winter.

45. As a bonus, let's now look at a few more pictures of Nattavaara again. These are taken the following day, when I was leaving, and the weather was already back to being perfectly normal. This is Nattavaara by; it's located on a hill and from here you can see snowy mountains far ahead on the horizon. I'm not sure what is the thing on the left is about, maybe it's a very tiny chapel of sorts. Nattavaara doesn't have a proper church, only a prayer house.

46. There is a gas station. I was a bit wary to fill up at such a place, but the gas was fine (and not extremely expensive as it can be in such places).

47. There is also a village store/post office.

48. Nattavaara station on the Ore Railroad, the last station before Gällivare.

49. The most notable thing about the station is its waiting room. It's really tiny and awfully cute, and also has this oversized-looking regular timetable display, complete with buttons for vision-impaired passengers.

50. The inside of the waiting room. It's even got some books! I wonder how often this waiting room is ever actually used, particularly by tourists.

That's all for Gällivare and Nattavaara, and in the final part we'll look at the Laponian nature of Stora Sjöfallet and Muddus national parks, which is the whole reason I came to these lands in first place.