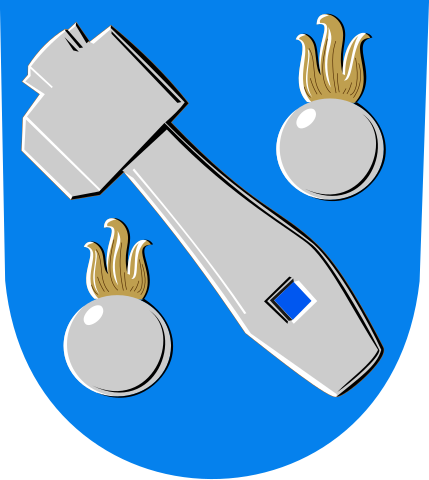

The Swedish-speaking town of Oravais (Finn. Oravainen), 50 km north of Vaasa, belonging to Vörå Municipality in Ostrobothnia region, is the site of one of the seminal battles of Finnish history. On 14.9.1808 in the Battle of Oravais the fate of Finland was essentially sealed: it would cease to be a part of Sweden and would join Russia for over a century. Let's start with some background information on the war.

The last Russo-Swedish war of 1808-1809 is known as Finnish War (Suomen sota) in Finland for this very reason. The war, however, was not originally fought over Finland, but rather was a part of the Napoleonic wars; you almost could call it a proxy war of Britain and France. By 1808 most of Europe, including Russia, was subjugated by or allied to Napoleonic France, and participated in the Continental System, a wide-scale embargo against Britain, whose navy Napoleon was unable to defeat by force after the crushing defeat at Trafalgar.

Sweden was one of the far and few allies of Britain; King Gustav IV Adolf despised Napoleon and believed him to be the literal Antichrist. Under the Treaty of Tilsit of 1807 Tsar Alexander I agreed to force Sweden to join the embargo by Napoleon's request. Britain encouraged Sweden to resist and provided it with some funds and ships. Sweden refused to accept Russian ultimatum, and the war broke out on 21.2.1808. Sweden was in an exceptionally difficult situation; Denmark, allied with France, also declared war on it.

Most of the major battles of the war took place on the Finnish soil, most of the troops fighting on the Swedish side were actually Finnish, and, of course, the outcome of the war was that all of Finland was ceded to Russia. And so for Finland it became a patriotic defense war.

Swedish war plan was to defend at sea fortresses of Sveaborg (Suomenlinna) in Helsinki and Svartholm at Loviisa at all costs, and on land to retreat all the way to North Ostrobothnia, awaiting reinforcements once the sea thaws in spring.

Swedish troops indeed retreated according to that plan, having dealt several tactical defeats to Russians, but Sveaborg, considered nearly impregnable, surprisingly surrounded to Russians after a brief siege in May 1808 (and lightly defended Svartholm even before that). Reasons for Sveaborg's capitulation remain unclear to this day. Vice Admiral Cronstedt, the commander of Sveaborg, has traditionally been considered a traitor or at best a coward; this view has been questioned by some historians. Either way the loss was catastrophic.

Swedish counteroffensive started in summer with mixed success, and by the end of summer the Swedish army was mostly spent. Despite some tactical victories and successful landings on Finnish shores, in the end only minor gains in Ostrobothnia were made.

The horrors of the Greater Wrath (isoviha), Russian occupation of Finland in 1713-1721, strongly reminding of ongoing Russian occupation of Ukraine today, were mostly avoided that time. But not entirely; for example, the city of Vaasa was sacked and burned for aiding the Swedes.

Russia began to press on to the north again by autumn. General Carl Johan Adlercreutz, Swedish commander at the time, decided to defend at Oravais, where some good natural defensive positions were available. The Swedish army at the moment was 5000 men strong, Russian 7000 strong.

(Adlercreutz family has been prominent in Finland to this day; right now we even have an Adlercreutz as a minister! (Anders Adlercreutz, Swedish Folk Party, Minister of European Affairs and Ownership Steering in the Orpo cabinet) But I digress.)

The bloodiest battle of the war ensued; 740 troops fell on Swedish side, and 900 on Russian side. Sadly, Adlercreutz fell into a Russian trap, counterattacking too far a seemingly beaten Russian force, leaving his great defensive positions and running into Russian reserves.

From Oravais onwards, Sweden permanently lost initiative and could only retreat farther north, its army crushed and demoralized. After the Ceasefire of Olkijoki in November Swedish troops left the territory of Finland entirely, never to return back. The battles of 1809 happened on Swedish soil, further beating Sweden into submission. King Gustav IV Adolf was deposed in a coup in March 1809, and peace was signed in September. Tsar Alexander I pledged to keep Swedish laws and faith in Finland at the Diet of Porvoo in March.

Thus something that seems utterly insignificant now, over 200 years later, a disagreement about embargoing Britain, redrew the map of North Europe permanently, with the Finnish period of autonomy under Russian crown beginning, and Sweden becoming neutral... all the way until 2022.

The Battle of Oravais is, of course, the most famous thing about Oravais now. Signs for "battlefield" (Slagfält/Taistelutanner) point towards a monument on a rock, overseeing a field to the south. This is the very field where the battle happened; Adlercreutz commanded it from this rock.

The road going through the field also existed in 1808; it is the old Gulf of Bothnia Coastal Road (Pohjanlahden rantatie), existing since the 16th century, and the main road in the area until 1936. This stretch has a museum status now.

There are some WWII monuments next to the big one too, including one to Soldier Boys (Sotilaspojat), a volunteer youth defense organization in war years, these days a much less often remembered one than Suojeluskunta (White Guards) and Lotta Svärd.

Lotta Svärd is usually known as the name of the women defense organization in war years (and its members are called "lottas"), but the name actually comes from the Finnish War, from Tales of Ensign Ståhl, and hence there is also a monument to Lotta Svärd.

The best known literary work about the war is Tales of Ensign Ståhl (Fänrik Ståls sägner in the original Swedish) by J. L. Runeberg, published in 1848 and 1860. It is a romantic nationalist epic poem, telling about heroic deeds of officers and ordinary soldiers. The book has greatly shaped the perception of the war (and various characters related to it) in the Finnish psyche, and had a great influence on the Finnish national awakening. The words of the national anthem of Finland, Our Land (Finn. Maamme, Swed. Vårt land), are just the prologue of Tales of Ensign Ståhl. And Lotta Svärd (svärd means "Sword" in Swedish; it was common for Finnish soldier families to take such simple Swedish last names) was a fictional character from one of the poems of Tales of Ensign Ståhl, an older soldier widow who followed the Swedish army and cared for the troops.

The museum next to monuments is also called Ensign Ståhl Center (Fänrik Ståls center). Unfortunately I didn't visit it (as usual I was here out of opening hours). It is also known as Furir's House (Furirbostället); furir was a non-commissioned officer responsible for food supply. Furir's House is a real 18th century furir's residence, moved here from elsewhere in Vörå. There are also a couple of other old buildings (and sheep!). There are occasional historic reconstructions taking place here.

Also nearby is a restored soldier's croft (Soldattorp). Such crofts are where regular soldiers lived in Finland in the era of Swedish allotment system (Swed. indelningsverket, Finn. ruotujakolaitos), from the 1680s to 1809. The system meant that every 2-6 peasant houses had to provide and equip one soldier. They also had to provide this solder and his family with a croft (house with a small plot of land) where they lived in peacetime. The system proved highly efficient in wars of the 18th century; it meant Sweden always had a trained army, which most other countries at the time didn't.

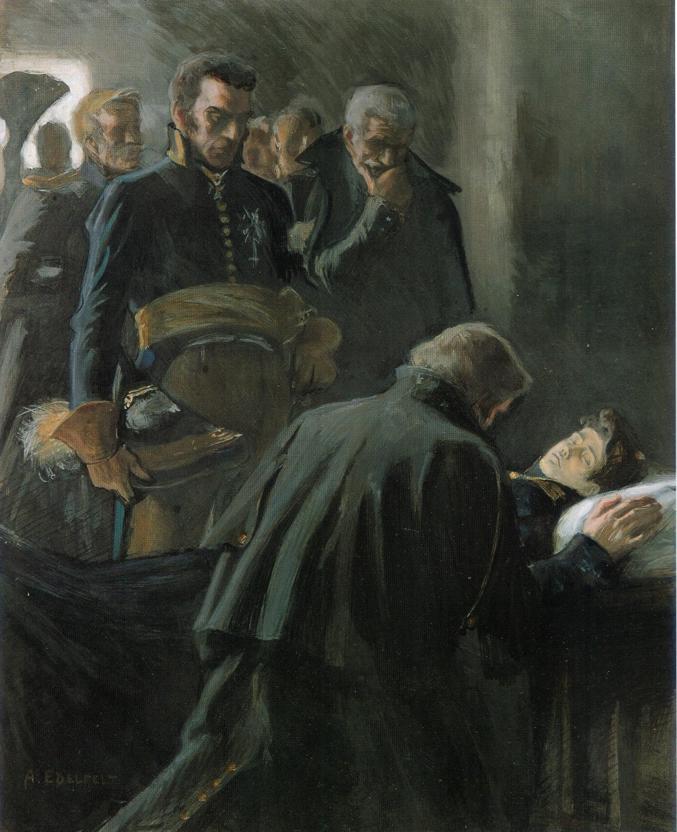

There are several other memorials of the battle in the area. Wilhelm von Scherin's bridge on another old, now disused stretch of the road leading to Vaasa was where the first clash of the battle took place. Ensign Count von Schwerin was only 15 when he commanded a battery here.

Von Schwerin's battery managed to hold off the Russians until the rest of the force retreated. Von Schwerin himself was badly wounded and died a week after the battle. The young hero, buried in Kalajoki in the north, was also immortalized in Tales of Ensign Ståhl.

It is however still unknown where most of the dead Finnish/Swedish and Russian troops were buried. Some remains of Russians, including one officer, were found during the construction of the modern Road 8 Vaasa-Kokkola in 1955, and a small monument stands by this road now.

A few other remains were found over the years, but nowhere near all of them, despite extensive searches. And most people driving here on Road 8, one of the most important Finnish roads following the Bothnian coast, probably don't give too much thought to the battle of 1808.