Loviisa: Svartholm Fortress

Published on:

Svartholm (Swed. Black Island) is a ruined 18th century Swedish sea fortress on an isle in the Gulf of Finland, in the mouth of Loviisanlahti Bay, 8-9 km off the coast of the town of Loviisa. The biggest sight of Loviisa, Svartholm is absolutely worth a visit. Unfortunately it seems it is only really possible for less than two months in summer (mid-June to early August), when a scheduled boat from Loviisa operates. With a private boat it should be possible to visit Svartholm any time around the year. (Loviisanlahti freezes over in winter but I’m not sure whether the ice is normally thick enough as far out as Svartholm.)

I’ve briefly covered the history of Loviisa and Svartholm in the previous post, so there won’t be a big history lesson. The fortress was constructed by Field Mashal Augustin Ehrensvärd (same guy who designed Suomenlinna) after the War of Hats of 1741-1743. It was square-shaped, with four bastions in the corners, two ravelins beside the fortress, and an irregularly-shaped wall around the isle. The fortress was used as a sea base, but due to insufficient funding and incomplete construction it wasn’t able to put up real resistance in the Finnish war of 1808-1809, and surrendered to the Russians. After Russia annexed Finland Svartholm was used as a prison. Some of the Decembrists (officers who rebelled against Russian absolute monarchy in 1825) were imprisoned here, although the same can be said of virtually any fortress that belonged to Russia at the time. Svartholm was shelled and destroyed by the British fleet in 1855 as part of the Crimean War (even though it didn’t have any significant military value at the time). Ruins were well-preserved and partially restored in the second half of the 20th century. Nowadays Svartholm is a great picnic destination as well as a historical monument; visiting Loviisa is worth it for Svartholm alone. It is administered by Metsähallitus, Finnish Forest Administration.

Visiting Svartholm (including its small museum) is technically free, but the round trip on a boat from Loviisa currently costs 18 €/person (9 €/child). Boat schedule is available here: https://visitsvartholm.fi/reittiliikenne/ (Finnish only but should be clear enough). As you can see the 2017 season is over. Note that the boat, as of 2017, operated only from Wednesday to Sunday (Keskiviikosta Sunnuntaihin). The website suggests buying tickets online in advance, which could make sense during Finnish vacation season in July. Myself, I travelled to Svartholm the very last day of the season; there were only a few other passengers, and I bought a ticket when boarding without any difficulties. The boat, named Taxen, departs from the end of a long pier (the one with gas station for boats) at Laivasilta Harbor. It’s not big and might be a little difficult to find, but can be also identified by a small blue "Svartholm" sign on its front.

Loviisa: The Town

Published on:

Loviisa (Swedish spelling: Lovisa) is a Finnish town in the east of the capital region, 90 km east of Helsinki, on the coast of the Gulf of Finland, about halfway between Helsinki and Russian border; a rather small one, with the population of about 15,000. Of the four cities along the National Road 7, commonly passed by Russian tourists (including myself) on their way to Helsinki, Loviisa is the smallest, and likely the least often visited. For me it was the closest Finnish town where I had never been before, so that’s why I decided to choose this destination in first place.

Loviisa was founded in 1748, soon after the Russo-Swedish War of Hats (1741-1743). In the period between the Great Northern War (1700-1721) and the War of Hats Sweden, for some reason, mostly ignored the question of defense of its Finnish territory, despite having just lost a good chunk of it (including Vyborg) to Russia. The War of Hats was revanchist in nature, and apparently Sweden assumed it would generally be on the offensive side in that war. Well, they were mistaken, and another chunk of Finnish land, including fortresses of Lappeenranta, Hamina, and Savonlinna fell to Russian hands.

Thus Sweden was in a great hurry to build some new fortresses: Sveaborg and Svartholm. Sveaborg, near the (then very minor) town of Helsinki, was to be the great impregnable fleet base; it is currently also known as Suomenlinna, and is the best known attraction of Helsinki. The much smaller Svartholm was to be the new frontier fortress, replacing Hamina (Fredriskhamn) in that role. The construction of both fortresses started in 1748, under the command of Field Marshal Augustin Ehrensvärd.

Ruotsinpyhtää: Kukuljärvi Trail

Published on:

Kukuljärvi (also known as Skukulträsket in Swedish, which is also commonly used in Loviisa area) is a small forest lake to the southwest of Ruosinpyhtää. Its shores are a minor natural protected area. A 8 km circular hiking trail goes from Ruotsinpyhtää to Kukuljärvi and back, and is one of the most popular hiking trails of Loviisa Municipality. Loviisa is not a very big municipality, in territory as well as population, and does not have any national parks or other major hiking areas, but Kukuljärvi is actually pretty nice. It’s been a while since I’ve last been in the Finnish forests, so after I explored the heritage ironworks in Ruotsinpyhtää I walked back to the car, put on my hiking shoes, and set out.

The trail is documented on the Loviisa Municipality website, in Finnish only, but there’s really only a map anyway. The trail is well-visible throughout its entire length and well-marked, which is a good thing as the map isn’t really detailed enough to find your way in the woods. It has a few relatively steep spots but overall should be easily walkable by nearly anyone. Very few muddy parts as well, at least in reasonably dry weather.

Ruotsinpyhtää: The Ironworks

Published on:

Ruotsinpyhtää or Strömfors is a village in Loviisa Municipality in Uusimaa (capital region), Finland. Located about 20 km away from the town of Loviisa, it is notable as the site of old ironworks, which now operates as a museum.

The ironworks was originally founded in 1698 by some baron Johan Creutz. In 1743 Sweden lost the War of Hats to Russia, and a new border was drawn along Ahvenkoski (Finn. Perch Rapids), the western lower arm of Kymi River. The old parish of Pyhtää was split in two, and its western part eventually became known as Ruotsinpyhtää: Swedish Pyhtää. Soon after the war, the ironworks was bought by Anders Nohrström and Jakob Forsell, local merchants. They greatly expanded operations, and named the ironworks Strömfors (Swed. something like Current Rapids, but actually a made-up word from their surnames). Forsell eventually became knighted (and got an "af" in his surname), and his dynasty owned Strömfors up until 1886. The golden age of Strömfors was under Virginia af Forselles, who owned and managed the ironworks itself from 1790 up until her death in 1847. Most of the surviving Strömfors buildings date to Virginia’s era. She was intimately familiar with the ironworks operations, paid generous salaries, and was greatly respected by the workers who called her "Her Grace".

Strömfors was bought in 1886 by Antti Ahlström, the founder of one of the biggest Scandinavian manufacturing companies. In 1947, a new electric and plastic accessories factory was founded nearby by Ahlström; it was later sold to Schneider Electric, and was shut down in 2014. Meanwhile the old ironworks was shut down in 1950, and later was converted into a museum where you can get familiar with how it all used to work. There are restaurants, small craft shops, and galleries. The whole thing reminds me of Verla cardboard factory, which, conincidentally, was also an old factory powered by the Kymi River, significantly upstream of Ruotsinpyhtää. Although Verla might be a bit larger.

As far as I understood Strömfors didn’t actually smelt its own iron, working on imported Swedish metal instead. Thus it does not have any blast furnaces, which I didn’t know beforehand and which made me slightly disappointed. It was purely a metalworking operation.

Ruotsinpyhtää ironworks is one of the main sights of Loviisa municipality (it used to be the center of its own municipality, but was consolidated to Loviisa since 2010). It is signposted from the main Road 7 (Ruotsinpyhtää Ruukki/Strömfors Bruk) and easily accessible by car. The place is worth visiting mainly on summer weekends, when it gets full of life (you can see the detailed opening days at their website, only in Finnish though). Loviisa tourist website claimed that on the day when I got there Kymi River Festival was held in Ruotsinpyhtää. I didn’t see anything to do with Kymi River in particular but the place was certainly crowded by Finnish standards.

Southeasternmost Finland and Valkmusa

Published on:

I took a weekend trip to Finland in early August. I was abroad for the first time since my 5.5 week long vacation in Northern Sweden and Norway in May-June which, of course, I still have to write about someday; I’m not even finished with sorting the pictures from that trip yet. I have a pretty huge backlog of trip reports, actually, but hopefully things will become easier with my reworked blog.

I chose Loviisa, a town on the southern coast of Finland, as my primary destination, but I also intended to see Svartholm fortress and Ruotsinpyhtää iron works and hiking trail. But first of all I wanted to do something which I’d been thinking about for some weeks: going to the southeasternmost accessible point of Finland.

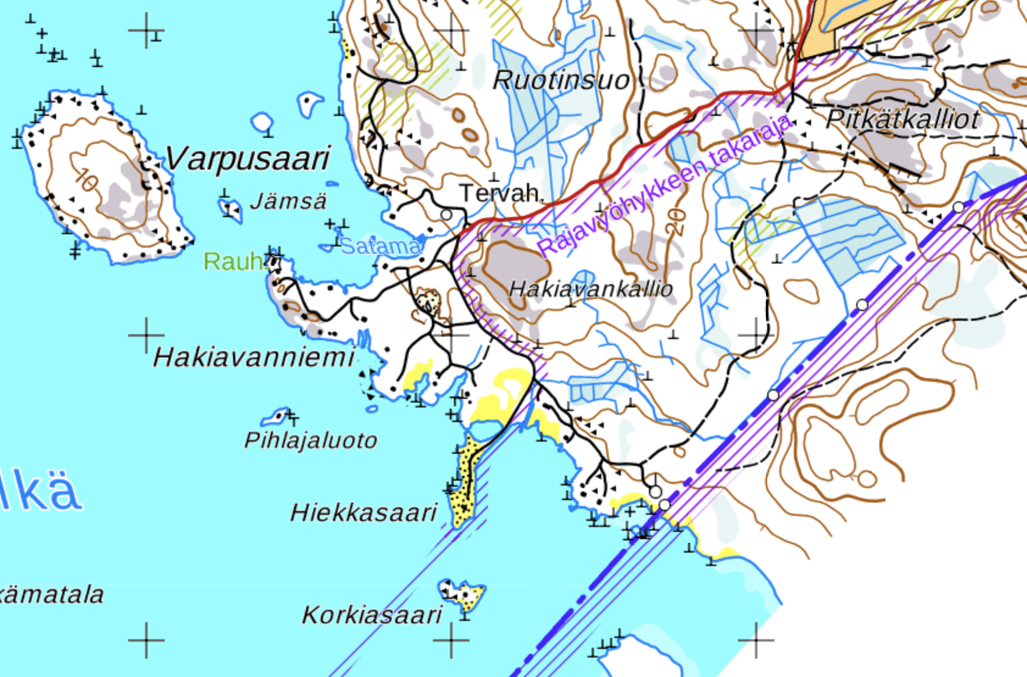

By this, I mean the point where the Finnish-Russian border starts at the Gulf of Finland. There is of course a restricted zone near the border, which is mostly a few hundred meters to a few kilometers thick on the Finnish side. It cannot be visited without a special permit, and is monitored by the border guards service. This zone is clearly marked and there is no danger in wandering there by accident if you pay some attention.

So according to the topographic map, the southeasternmost point without restrictions (the restricted area is marked with violet shading here) is a sandbar appropriately named Hiekkasaari (Finn. Sandy Island), about 450 m from the actual border, and there is some sort of road going there:

To save you the suspense, no, I couldn’t visit Hiekkasaari. Drove all the way to the last fork in the road, but the final part was marked as private area (Yksityisalue — a useful Finnish word to know) and I couldn’t go there. Well, at least now I know.

Savonlinna

Published on:

Savonlinna (Finn. Savonian Fortress, after Savo province of Finland), population 35,000 is, in my opinion, one of the nicest of the smaller Finnish towns. Located on islands in Saimaa Lake, and basically surrounded by water from all sides, it is incredibly cozy and beautiful. Furthermore, it has a fairly big attraction, the medieval castle of Olavinlinna, one of the very few medieval castles preserved in Finland in mostly original shape.

Savonlinna is located in Southern Savo (Etelä-Savo) region of Finland, somewhat in the middle of Imatra-Joensuu-Varkaus triangle. This part of Finland is basically a maze of lakes, and most of Savonlinna is located on a few islands in a strait between two expanses of Saimaa lake system. It can be reached via National Road 14 from Juva (branching from Road 5, from the general direction of Helsinki), or from Parikkala (branching from Road 6, from the general direction of Russia). Savonlinna is fairly close to Russian border (120 km from Svetogorsk-Imatra border crossing checkpoint) and thus is a common destination for Russians on weekend trips.

Savonlinna should not be confused with Suomenlinna, a sea fortress in Helsinki, and probably Helsinki’s best known sight. I know I used to confuse them some years ago :)

So far I’ve been to Savonlinna twice, and these pictures are from a weekend trip with friends in November 2015.

Joensuu

Published on:

Joensuu (Finn. River Mouth) is a Finnish city of about 75,000, and the capital of Finnish Northern Karelia (Pohjois-Karjala) region. The eponymous river is Pielisjoki, which flows from Pielinen Lake into Saimaa lake system. Joensuu was founded in 1848 as a center for commerce, and throughout its history, well, nothing really particularly important ever happened here. So this isn’t the most exciting city ever, even by Finnish standards. Still, it’s quite nice as all Finnish cities are, and probably worth a look if you happen to be nearby and got some time to spare. Probably not actually worth a trip by itself (although the region of Northern Karelia is quite interesting, probably the coolest Finnish region after Lapland of course).

I mostly know Joensuu as the first city on the way north (into Lapland and the like) when driving from Russian border, a 200 km drive on Finnish Road 6 after the border towns of Lappeenranta and Imatra. The first time I actually visited Joensuu was in late October 2015. Yeah, I’m starting to post some pretty old stuff here. Well actually I’m finishing a draft I began back in April 2016 mostly just to get a feel for my new blog workflow with WordPress. So far it feels fairly nice!

When going from St. Petersburg to Joensuu or father to the north of Finland, it is possible to pick an alternate route, not via the traditional Scandinavia Route and Lappeenranta/Imatra, but via Sortavala Route through Russian towns of Priozersk, Lahdenpohja, and Sortavala, and Värtsilä/Niirala border crossing checkpoint. This option is slightly shorter than the usual one, but the fraction of the route going on Russian roads is much greater. The roads themselves are of questionable quality, with a short gravel section after Priozersk, and generally really winding between Lahdenpohja and Sortavala. Nonetheless, the traffic is much lighter and safer than on the Scandinavia Route (excluding the section closest to St. Petersburg, but nearly all of it has already been rebuilt with near-motorway quality). I wrote about Sortavala Route in more detail in this post (available only in Russian). The road continues to be improved and some details from that post are already obsolete.

From GitHub Pages to WordPress

Published on:

So in the end I migrated this blog of mine (which ended up being mostly about travelogues) from GitHub Pages to WordPress. If this doesn’t mean anything to you, you can probably skip this post safely.

Why? I mean, GitHub Pages are so hip and WordPress is literally one of the words pieces of software imaginable, right? Well, simply put, GitHub Pages are not really a good fit for travelogues. GitHub Pages, if you didn’t know, is a very simple hosting option available at GitHub (which is mostly about hosting software project code). It is free but all it can show is static HTML pages, or Jekyll templates. Jekyll is the most popular of static site generators these days. These generators take templates written in their own specific languages, and convert them to HTML pages. This is all done locally (or in case of GitHub Pages, on GitHub servers), and all that is ever actually served to website visitors is static HTML.

This is actually quite an appealing concept. It naturally limits interactivity, but most websites arguably don’t really need any interactivity at all. And these days, if you want comments, for example, you can just slap a Disqus widget onto your website — this way you’ll have someone else take care of your comments, and won’t need anything to run on your server. So you can just write your pages/posts in plain HTML or Markdown, and have header/footer/menu/index pages generated by Jekyll. Well not necessarily Jekyll, these days there are hundreds of static site generator projects. But Jekyll’s the most popular, and the only one natively supported by GitHub Pages. An additional advantage is that you can use your favorite text editor, and edit your posts offline, just pushing them onto GitHub whenever you like.

Well, it turns out, this workflow is fine for a basic website with a few pages, possibly about some software project or whatnot, or for a simple blog which doesn’t have many pictures. In fact I believe both of these use cases are precisely what GitHub Pages were designed with in mind. But when you write travelogues, it is mostly about pictures. And when you need pictures, static site generators begin to suck ass.

Helsinki and Vantaa in Late November. III: Vantaa

Published on:

Vantaa is one of the two major satellite cities of Helsinki, along with Espoo. With the population of 215,000, Vantaa is a bit smaller than Espoo, and unlike Espoo it is landlocked, being located to the north of Helsinki (Espoo is to the west, enjoys a long shoreline, and includes a large number of islands and skerries). Otherwise it is mostly indistinguishable from Espoo though; a mishmash of mostly residential neighborhoods, most of them built from about 1950-1960s to the present day, often separated by small forests or other natural features.

I already told the brief history of Vantaa (formerly known as Helsinge parish village) in the previous part. Like Espoo, Vantaa predates Helsinki itself but it has been a minor village for the majority of its existence. St. Lawrence Church is one of the few relics (if not the only one) of the old Vantaa. The current administrative center of Vantaa is Tikkurila neighborhood as that’s where the city council and other services are located, but otherwise Tikkurila is not particularly special.

You might have heard of Vantaa from the name of Helsinki-Vantaa Airport, which is indeed located in Vantaa, 20 km from central Helsinki. In fact the airport splits the dumbbell-shaped Vantaa nearly in two. Like many big cities Helsinki outgrew its original airport named Malmi, which is located closed to the inner city, and has been repurposed for general aviation (and will probably be closed down in future).

We’ll have a look mostly at two Vantaa neighborhoods, named Kartanonkoski and Tikkurila.

Nord-Norge '16. II. Our trip in brief

Published on:

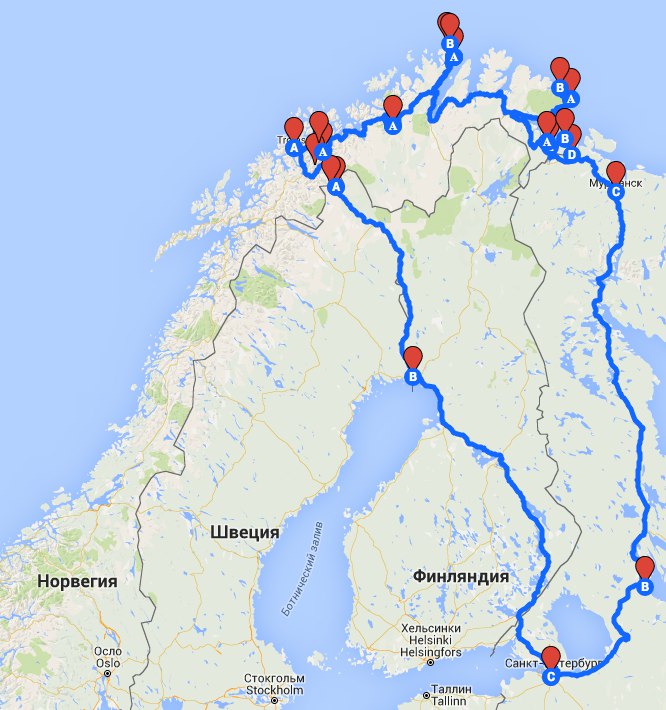

As a matter of fact, there are two ways to drive to Northern Norway from St. Petersburg, Russia. First, you can go through Finland. It’s a pretty safe bet; the quality of the roads is very nice, the traffic is fairly light, and there are many routes you can choose. There are six border crossings from Finland to Norway. The only downside is that driving through most of Finland is relatively boring. Apart from some parts of Lapland and Karelia, the views are decidedly unimpressive. Unless you happen to like trees a lot, I mean.

The other option is, of course, going through Russia! I got my driving license in January 2013, and clocked at least some 70,000 kilometers by July 2016, but I was still very wary of driving extended distances in Russia. Narrow and sometimes poor roads, lots and lots of suicidally reckless drivers, and usually quite significant traffic with a lot of overloaded trucks do not really make for a nice driving experience too. Still, the St. Petersburg — Petrozavodsk — Murmansk — Norwegian border road, the Kola Route (signposted as M-18 or more properly R-21) was, as far as I knew, a fairly nice one as far as Russian roads go. And we’d get to visit two major Russian cities we would be unlikely to visit otherwise: Petrozavodsk and Murmansk!

So in the end we decided to go to Norway via Russia, and back via Finland. Over overall itinerary looked like this:

The letters do not mean anything, sorry. It’s surprisingly difficult to draw a non-trivial map with Google!