A few days ago I had a walk in the vicinity of the village of Siuntio (Swed. Sjundeå), about 40 km west of Helsinki. A curious place; there are still city buses of Helsinki area and even commuter trains on weekdays, but the landscape is alread completely rural, with no new apartment block construction or anything else of the sort. So I was walking on a country road, and then, behind a bend, an inscription in Russian suddenly appears! "A serviceman must value the honor and battle glory of the Armed Forces of the Union of SSR, his unit and the honor of his military rank..."

Although I hadn't really known about this particular place, overall this is not an especially surprising find in this particular region of Finland. Siuntio belonged to Porkkala area, leased out to the USSR in 1944-1956. I wrote about Porkkala in more details in a later post, but here is a brief version.

As early as during the negotiations between Finland and the USSR about possible territorial exchanges in the autumn of 1939 the main stumbling block was the uncompromising desire of the USSR to have a naval base in South Finland. Although the desired territorial exchanges on the Karelian Isthmus (which are generally far better known as the reason for the ensuing Winter War) could in theory be acceptable to the Finnish side, a base at Hanko in 120 km from Helsinki would have immediately become "a gun pointed into the heart of Finland". As we all know, the USSR eventually got what it wanted and more by military means, and in 1940-1941 Hanko area was leased out for its naval base; in the Continuation War in 1941 a whole separate front line emerged there, but eventually the Soviets were forced to evacuate the base. Among 1944 peace terms the new requirement by the USSR was now not Hanko but rather the so-called Porkkala area, even far closer to Helsinki; its border would have passed just 20 km from Helsinki center (nowadays Helsinki urban area has actually already reached that old border).

Of course, Finland didn't have much of a say at the time. About 7200 people were evacuated from a territory of 380.5 km; mostly villages of Kirkkonummi, Siuntio, Degerby. The Soviets built a harbor in the Båtvik bay, and fortifications on the peninsulas of Porkkalanniemi and Upinniemi. This was technically a lease, not an annexation; the USSR was paying Finland for the area, and the lease had a fixed term (of 50 years, until 1994). The Finnish side nonetheless considered the area lost for all practical purposes for the foreseeable future, and the evacuees were granted new plots of land, on the same terms as for the far more numerous evacuees from the Karelian Isthmus and Ladoga Karelia.

The decision of the USSR to return the area to Finland prematurely was a complete surprise for the latter. The USSR decided that the upkeep of the base was too expensive, and its usefulness in the geopolitical situation of the 1950s was already questional. Finland, of course, sighed with relief; President Paasikivi declared "for the first time in my life I return from Moscow satisfied".

In January 1956 the USSR finished its withdrawal and officially returned the Porkkala area to Finland. In theory, the area was to be returned in the same condition as it had been leased before. In particular all military installations were dismantled or demolished. Old Finnish buildings, however, generally were left in a poor state, with many demanding a lot of repair. Each of the evacuees had a choice: either return the land they had been provided with after the evacuation, or give up their old Porkkala houses and land to the state, or keep both but pay the appropriate compensation to the state. All in all the vast majority chose to return to their homes. The USSR also had left some infrastructure, for example, a local road that is still called Kabanov Road (Kabanovintie) after the local commander, or a rail spur to the harbor that consequently was used by some Finnish industry; up until it was dismantled in 2006 there still had been original Soviet rails on it. Only a handful Soviet buildings remained, mostly quite unremarkable; they are all privately owned now and not easy to find. Many smaller remaining artifacts of the Soviet era have been collected in the Igor museum in Degerby.

The building on the title picture is, however, not Soviet-built; this is the former bakery of Sjundby manor, about two kilometers east of Siuntio. Sjundby is actually a rather remarkable manor. Its original owner was Jakob Henriksson Hästesko, the stablemaster of King Gustav Vasa and the most high-ranking Finn in his entourage. Hästesko continued his service for King Eric XIV, was the warden of the Vyborg Castle for a while, but died in 1567 as a prisoner of the Danes. The manor building was built already without him present, in about the same time, the 1560s. There aren't many manors in Finland that would be so old, and Sjundby looks quite unusual, with its masonwork and overall size and shape reminding more of a castle. It is indeed sometimes called a castle, although that is wrong; it never had a military or administrative role.

After Hästesko the owners of the manor were the House of Tott, his relatives, and in that era the manor had its most noble lady ever: Princess Sigrid Vasa, daughter of the Mad King Eric XIV and his Finnish Queen Karin Månsdotter. Although Eric was overthrown by his brother Johan, Sigrid, like her mother, was allowed to keep her holdings in Finland. After the Totts, the manor passed to the Adlercreutzes, the noble family whose most famous member was Carl Johan Adlercreutz, the famous Swedish general of the Finnish War of 1808-1809.

The Adlercreutzes, whose dynasty originated at Lohja, very close to Sjundby and Siuntio, have owned the manor for the last three hundred years, or, more precisely, the current owners are the Segersvens, a branch of the Adlercreutz House. Margareta Segersven, the current lady of the manor, has seen the Porkkala evacuation as a child, and returned to Sjundby as a teen. The manor, which had been located at the very edge of the lease area, had been used as troops quarters, and required massive restorations after the return, lasting many years. At least the furniture and everything else movable was not damaged; these belongings had been taken along in the evacuation. Nowadays Segersvens or their relatives are generally glad to give tours of the manor; I actually saw a bus with Russian license plates and tourists near the manor.

Let's now have a look both at Sjundby and at the rest of Siuntio. I originally only planned to write about Sjundby, but Siuntio is not a huge place overall, so why not.

1. Sjundby manor main building.

2.

3.

4. The manor is built at the rapids of the Siuntionjoki river (Swed. Sjundeå å). This smallish river, flowing from Enäjärvi lake at Nummela in Vihti, about 50 km long, is considered one of the best preserved in natural state rivers of the Uusimaa Region of South Finland. Among other things it has a population of sea trout. The river has never been dammed, except this dam at Sjundby that doesn't block the flow completely. The dam is still used to this day by a tiny private hydro power plant, serving only the manor itself. I don't remember seeing such manor hydro power plants before in Finland, although most probably there are a few more.

The Ecolines bus from Russia leased out for some tour is also visible in the picture. I had first seen it in the center of Siuntio and had wondered what anyone from Russia was doing here.

5.

6. Crossroads.

7. Pancake ice on the river below the rapids.

8.

9. Now let us return to the Siuntio center. Classic rural Finland :)

Siuntio today is a rural municipality with an area of about 250 sq. km (excluding sea areas) and the population of about 6200. 66% of the population is Finnish-speaking, 29% is Swedish-speaking, the rest have other mother tongues. The population of Siuntio has been slowly growing, which is unusual for Finnish countryside that tends to slowly die out; presumably this is because of the closeness to Helsinki area. The biggest village of Siuntio is its station village (asemanseutu). It is home to about 2300 people and nowadays generally synonymous with Siuntio itself. The church village (kirkonkylä), the old center of Siuntio, is located a few kilometers north of the station one, and is quite small with only 350 people. Virtually all of the basic services are in the station village. Apart from these two villages, the population is mostly dispersed.

The origins of the "Siuntio" name are not known definitely, but almost certainly the Swedish version, "Sjundeå", was the original one. It sounds similar to Swedish sju, which means "seven", and a popular version states that Sjundeå meant the seventh river, counting from the Aura River in Turku (old capital of Finland) to the east. Or maybe it's just from an old Swedish name of Sjunne.

10. Siuntio is most easily reached by own car, but it also belongs to the HSL (Helsinki area public transport) service area, and thus you can get there by Helsinki tickets, which was the option that I took. Unfortunately commuter trains here don't run on weekends, and the only thing that does run is a bus with only two departures from Kirkkonummi in the day, on late morning and late afternoon. Kirkkonummi is a town between Siuntio and Helsinki urban area, much bigger than Siuntio, and commuter trains do run there even on weekends, every 30 minutes. So I went to Kirkkonummi by train from the Kilo station near my home in Espoo (a satellite city of Helsinki), and then by morning bus. Its main stop in Siuntio is at some backyards across the supermarket.

11. The "kioski" little convenience store in the station village (pictures are not in strict chronological order, thus the randomly appearing and disappearing snow). Such stores usually also serve as post offices, but it's curious that this one is not from the ubiquitous R-Kioski chain, but rahter someone's independent store.

12. Ah, doesn't it all look heartwarming!

13. There is a handful of small older apartment blocks in the village, but no new construction.

14. Virtually the only actual sight of the Siuntio station village is the torp ("torp" means a small plot of land and a house in rural area, leased out to some landless peasant) of Fanjunkars. The torp is notable becase this is where Aleksis Kivi, a writer, lived and worked in 1864-1871. Aleksis Kivi is considered one of the most important Finnish writers, because he was the first one who actually was writing in Finnish; such figures as Topelius and Runeberg before him loved Finland to be sure, but were writing in Swedish, as it was their native language and Finnish overall began to get some real hold only in the second half of the 19th century. Kivi was a native Finnish speaker, even though his original last name was also Swedish (Stenvall). As is appropriate for a real writer, he was poor, had mental issues, suffered from alcoholism and died at the age of 38. Most of his works, including by far the best known one and the only novel, "Seven Brothers", he wrote here in Siuntio, where he was given a place to live by the torp owner Charlotta Lönnqvist, a spinster and a daugher of a poor officer. Lönnqvist wasn't exactly well-off herself, and was later known as "the poorest philantropist of Finland", but still apparently had some sort of sympathy towards Kivi; although it is not known whether they actually had any kind of a closer relationship. Kivi lived at her torp until his health failed completely; in 1871 he ended up at a mental hospital, where he was diagnosed with schizophrenia due to alcoholism and "wonded writer's feelings", and died the next year in a house of his brother Albert in Tuusula. After Kivi's death Lönnqvist got a personal pension from the state, and her torp was eventually declared a monument.

Unfortunately the Fanjunkars torp building didn't actually survive the Porkkala lease of 1944-1956; the Soviet troops apparently didn't consider the small house as valuable and dismantled it down to its foundation (even though it is claimed that the evacuees left a letter in Russian in the house, asking specifically to preserve the torp). The building was rebuilt from scratch according to preserved images in 2003-2006, using funds from the municipality, state cultural foundation, local parish and private sponsors.

15. Memorial sign at the torp.

16. Kindergarten.

17. Cafe and pet store. It's always interesting to see specialized non-chain stores in small towns and villages. This pet store, as I understand, is more of a horse store than a cat and dog one.

18. This is a school I believe, and a health station should be somewhere nearby. Or the other way around. There are two schools in Siuntio, a Finnish and a Swedish one, and this is a Swedish one.

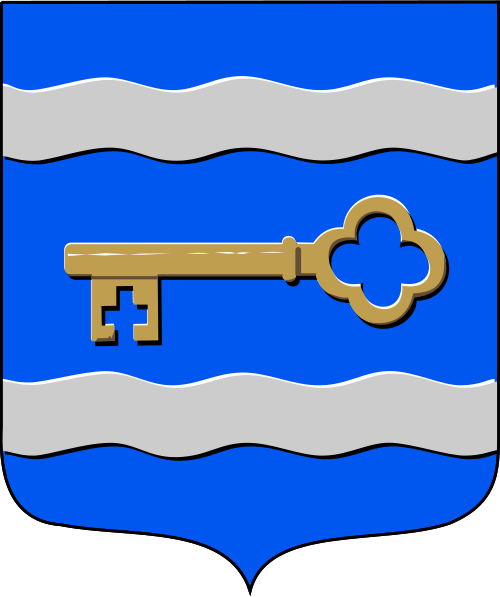

19. Municipal administration in the background, with the Siuntio coat of arms, picturing a key. The key means St. Peter, and St. Peter is the saint to whom the old medieval church was devoted. Siuntio's modern slogan is "Siuntio, the key to happiness" (Siuntio — avain onneen).

20. A whole nightclub in Siuntio looks shut down; there is a "for rent" sign on the door, and its Facebook page hasn't been updated since 2018. It looks like Siuntio doesn't have a single proper bar of its own currently, which is probably the worst thing about living there.

21. There is still some modern-looking residential construction in the village, represented by rowhouses.

22. A sign near the railway station announces an apartment block construction also, but considering that the year stated is 2015, the idea was apparently rejected.

23. And yes, the railway station! Siuntio is mildly notable for the fact you can reach it by a commuter train straight from Helsinki central station. Commuter trains in Helsinki are generally meant to serve more populated and urban places, and trains to the west, on the Coast Railroad, haven't been running to Karjaa and Inkoo since 2016. The terminus station in that direction is now Siuntio, which got worried enough that it joined the HSL public transport area just to keep its commuter trains. The service is still quite sparse; Y-train Helsinki-Siuntio runs only on weekdays, 2-3 times in the morning and in the evening (single very early/very late departures of U- and L-route trains also reach Siuntio), 45-50 min en route. It would have been of course more interesting to go to Siuntio by train, but it was Saturday, so the only option was with a bus transfer at Kirkkonummi.

24. More precisely speaking this is not a station but just a passing loop; I saw a Pendolino train bound for Turku stopping there to pass a Helsinki-bound InterCity (nearly all Coast Railroad has only one track; the second track ends at Kirkkonummi). Long-distance Helsinki-Turku trains cannot be entered or left here. Earlier the station had more tracks and a siding to a brick factory, but no traces of that exist anymore (including the brick factory). HSL ticket machine looks rather out of place here. Just for fun I loaded a monthly ticket on my HSL card in it, it was just the time of month for that.

25. Safety of course comes first as always, and instead of a foot crossing across tracks or steep stairs there is a shallow underpass, as is quite normal for Finland.

26. Timetable for Helsinki. The last morning commuter train departs at 7:53. Finland is meant for people who wake up early :)

27. Pekka's local taxi phone at the station. "Smell a big shit" is scratched into the wall nearby.

28. Old station building is preserved, a recognizable small wooden building by Bruno Granholm (who designed a great number of old Finnish wooden station buildings) from 1899. Protected by the state, but sold off in 2007 for use as a private residence.

29. InterCity train on an overpass over the station village main road.

30. And we go onwards.

31. Small store, I didn't quite understand what it sells.

32. Local library looks like some storage building.

33. Farther in that direction, to the north on Road 115, the village ends quickly. The sidewalk/bike track still follows the road for a few kilometers more to the spa hotel and the church.

34. Farms afar.

35. Siuntio spa hotel, built in the 1970s and operating now under Scandic brand. I didn't expect to see a spa hotel here; seems like a pretty random place for it. But why not, I guess. It has quite a few cars and people around, so it must be popular.

36. Next to the hotel is the Lepopirtti manor (Finn. Rest Cabin), owned by the Miina Sillanpää's foundation. Miina Sillanpää (1866-1952) is was a major Social Democrat politician and workers movement activist in 1910-1950s. Born in a poor torp peasant family, working at a factory since the age of 12 and as a housemaid since the age of 18, in 1926-1927 she became the first woman minister in the country (social minister, to be precise). She particularly cared about the rights of working and single mothers, and thanks to her a system of motherhood houses (ensikoti) was established; these are houses where pregnant women or women with infants can get accomodation or necessary help if that is not possible at their home for some reason. Sillanpää was also a member of parliament for 38 years in total, with some breaks. Lepopirtti manor was bought in 1921 as a holiday home for domesic workers, and also has a museum room of Miina Sillanpää.

37. And not far away is the chuch village and the church, the oldest building of Siuntio, built in appr. 1460-1489. Late medieval era stone churches are relatively common for Uusimaa and Southwest Finland regions, and the architecture of the Siuntio church is also fairly common.

38. Traditional military graveyard and monument near the church.

39. Near the parish meeting house there is also an additional memorial table in honor of all Siuntio people who fought in the wars of 1939-1945.

40. Closed down store is unfortunately an ordinary sight for rural Finland. The building is still inhabited though.

41. Priest house (pappila) a bit away from the church village.

42. Rural landscape outside villages. According to the topographic map and online databases, there is some ancient sacrifice stone, with seven man-made cups in it, next to the steep cliff on the left, but it is apparently right in the backyard of the yellow house in the middle.

43. Someone's keeping horses.

44. The fields look annoyingly green for February. Well, this is the kind of winter we had in South Finland, the warmest one in the history of weather observations, and the permanent snow cover this year never came.

45. Siuntio-Kirkkonummi stretch of the Helsinki-Turku Coast Railroad not far from Sjundby manor. There is a pair of smallish tunnels in the area. I was considering waiting for the next train to take a picture at the tunnel, but decided it will not make a particularly great picture anyway.

46. Still I didn't want to wait the remaining two hours for the bus back from Siuntio to Kirkkonummi, so I went there on foot (walking in the end 28 km in a single day; I haven't done something like that in years). The road mostly didn't have any particular sights. I walked past Kela manor, a funny name, as Kela is actually also the name of the Finnish social service that is responsible for granting most kinds of welfare benefits. In the case of the manor though the original name was clearly the Swedish one, Käla. I haven't really noticed the manor itself, but its huge elaborate cowhouse from 1901 was right by the side of the road. Apparently nowadays it's home to a summer cafe and some occasional events.

47. Siuntio-Kirkkonummi border sign on the old road, the King's Road (Kuninkaantie). It is even actually called that on Siuntio territory, the Eastern King's Road. This used to be the main Turku-Vyborg thoroughfare since the Middle Ages. Nowadays there are rather few cars here (modern Road 51, Helsinki-Kirkkonummi-Karjaa, passes a few kilometers south of the King's Road, bypassing settlements), and the municipal border sign here is an old-style preserved one.

48. And the other sign that this is an old road is this stone kilometer sign, with numbers almost unreadable already. Such signs were used in 1920-1930s; later on the use of kilometer signs was abolished, and nowadays they can mostly be seen by the side of such older roads, which were the main roads until the modern straighter ones were built. Blue marking means this is the second-class national road (kantatie, Finn. main road); the modern Road 51 has the same category, although on modern road signs their numbers are marked on yellow instead of blue.